A federal judge last month ruled against the American Hospital Association and other hospital groups in their lawsuit against the Trump administration’s plan to require hospitals to publish the prices they charge consumers.

As a victory for consumers, that win on June 23 was short-lived as the AHA appealed the decision the next day. Then on June 30, the AHA asked federal health officials to delay the effective date of the federal hospital price transparency rule until the court case is settled.

Sarah Kliff and Margot Sanger-Katz of The New York Times wrote that the initial decision was a victory for the Trump administration, which sees pressure from patients as a way to control health costs. But at Axios, Sam Baker took a similar approach, but added an important caveat, first quoting from Judge Carl Nichols’ ruling that “The publication of charges will allow the agency to further its interest of informing patients about the cost of care, which will, in turn, advance its other interest — bringing down the cost of health care.”

Baker then added that some experts on price transparency are worried that making prices available to the public may cause hospitals and other health care providers to charge more. We covered this topic earlier in, “Will price transparency drive up health care costs?”

Regardless of what effect transparency will have on prices, it’s important to keep the issue of price transparency in perspective for several reasons, two of which I’ll cover here because they’re timely.

First, it may seem almost unfair during a pandemic to raise questions about what hospitals charge, what with the high cost of treating COVID-19 patients and the concurrent revenue shortfall hospitals have seen as they have to restrict routine procedures and elective surgeries. Mark Taylor has reported on this issue for MarketWatch, as we noted in “Time to track how the pandemic is hurting health care provider finances.”

Second, while it may or may not be unfair to ask hospitals what they charge, consumers still want to shop for hospital care and other health care services with some knowledge about what that care will cost, or how the quality of that care compares with that of other providers. To help fill the gap in knowledge about hospital prices, states have been taking steps to help consumers identify hospitals and services that are shoppable. A shoppable health care service is one that is not emergent. In other words, the consumer can consider where to go to get the best price or highest level of care, or both.

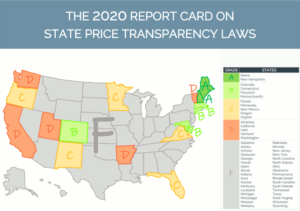

Catalyst for Payment Reform, an organization that promotes employers’ efforts to control costs and improve health care quality, in May released a report card on state efforts to improve price transparency. CPR produced the report with the Source on Healthcare Price and Competition (SHPC), at the University of California Hastings College of Law. CPR released five earlier reports on state price transparency laws but hasn’t done so since 2017. This latest report is the sixth installment of the Report Card on State Price Transparency Laws. (PDF, 6.2 MB)

“The costs of the COVID-19 pandemic and a severely troubled economy reemphasize the importance of transparency,” said Suzanne Delbanco, Ph.D., CPR’s executive director.

In this most recent report, CPR and SHPC show that 16 states have passing grades (on a scale from A to F) in their efforts to make accurate and more comprehensive price information available to consumers on the web. Only seven states got passing grades in 2017. The 16 states to get passing grades this time are:

- A: Maine and New Hampshire

- B: Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland and Massachusetts

- C: Florida, Minnesota, New Mexico, Oregon and Virginia

- D: Arkansas, California, Utah, Vermont and Washington

The other 34 states got failing grades. But the fact that consumers in 16 states have access to meaningful price data is important because health plans and providers themselves keep price information mostly to themselves, leaving consumers in the dark.