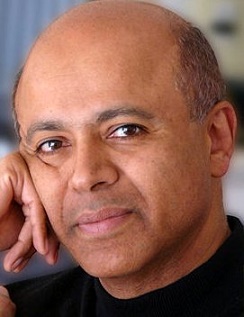

I used to be a Verghese virgin. I’d dipped into some of the Stanford physician’s New Yorker stories and read a few of his book reviews, but I hadn’t curled up with his nonfiction books that deal with medical care –“My Own Country” or “The Tennis Partner” – or, for that matter, his novels.

So I came to his speech on Thursday night at the Health Journalism 2015 kickoff session not knowing what to expect.

I came away charmed, and informed. His talk on the importance of bedside medicine and physical examination was as much a lesson in narrative journalism as it was a description of how he practices. (Speaking of which, where can I find an internist like him in Seattle?)

The first lesson came from AHCJ president Karl Stark, in his introduction. Verghese, as he said, is “an epic listener.” Name me a great writer who doesn’t share that attribute.

The jobs of doctors and reporters rely on stories. “Stories are the way we extract meaning from our experiences,” Verghese said. Stories can help doctors diagnose illness, and also put an experience into perspective. One of his own favorites is the death of the great writer-physician Anton Chekhov. Chekhov’s dying moments were eased by a country physician who, seeing the inevitable, gave Chekhov champagne instead of oxygen. Chekhov drained the glass, turned over on his left side, and died peacefully. Instead of the choking death throes of tuberculosis, Chekhov’s beloved wife “heard only peace, beauty and the grandeur of death.”

“I use the story to remind myself of the privilege of being a physician,” he said.

And one more parallel between medicine and storytelling – there’s always an epiphany. When Verghese started his medical career at the dawn of AIDS, he was faced with legions of AIDS patients and no way to cure them. His epiphany came when he realized that with a simple house call he could soothe a patient who couldn’t travel. “This was a revelation,” Verghese said. “This is what the horse and buggy doctors did so well.” Where they could not cure patients, they could at least heal them.

There were musings on metaphor and medicine (“metaphor is how we walk in others’ shoes”), of how he loves to read a patient’s history not through words but with a physical exam.

And like journalists squeezing their thoughts through a computer writing program, 21st century doctors populating restrictive computerized health forms are losing a level of meaning. “The i-patient is getting wonderful care,” he said, “while the real patient is saying ‘Where is everyone?’”

As for me, I have a couple of new books headed to my nightstand. I’m looking forward to learning about medical care in the 21st century, and I’m looking forward to some more great writing tips.