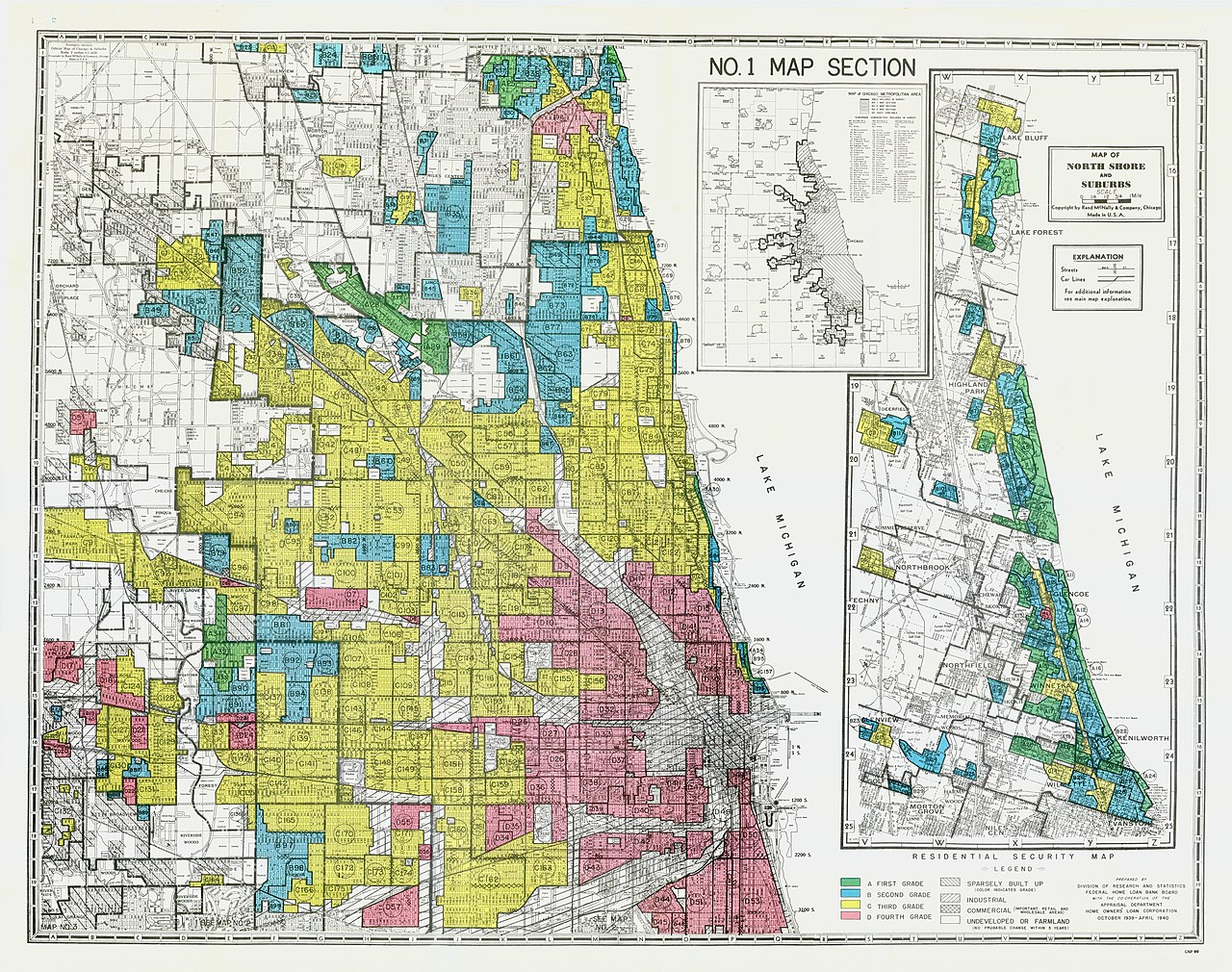

The enduring health impacts of redlining — an institutionalized practice that segregated communities by race for decades until it was banned in 1968 — are compounding.

A new study revealed that children and young adults with cancer who previously lived in redlined neighborhoods have increased risk of death. Researchers found that among the 4,355 children diagnosed with cancer, the survial rate at five years was lower among those living in redlined neighborhoods (85.1% versus 90.3%.)

Another recent study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that people living in formerly redlined neighborhoods in Philadelphia take significantly longer to achieve viral suppression after an HIV diagnosis.

Those in redlined areas needed, on average, six months to reach viral suppression — a key measure of effective treatment — compared to just four months for those in non-redlined areas. This disparity has persisted even after controlling for various demographic and clinical factors.

While the focus here is on HIV, previous research tells us the implications of redlining extend far beyond just one disease. People who live in redlined communities have a 3.6-year lower life expectancy compared to other communities.

Journalists can investigate why many historically redlined neighborhoods still face limited access to healthcare facilities, environmental hazards, and economic challenges. This requires scrutinizing not only historical policies but also present-day practices that perpetuate inequality, such as zoning laws, public transportation inequities, and ongoing investment disparities.

It’s also important to ask critical questions about accountability: What has the government or local authorities done to address these disparities? What role do healthcare systems play in perpetuating or alleviating inequities? By drawing connections between past practices and present-day policies, journalists can help readers understand that redlining’s health impacts are not just a relic of history but a modern issue that demands attention.

Health effects of redlining

People living in redlined ZIP codes face a variety of health challenges. Here’s what we know:

Studies have indicated that these residents are at higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease compared to those living in areas that were never redlined.

Mental health is another area of concern; individuals from formerly redlined neighborhoods report significantly higher rates of anxiety and depression. In fact, one study found that lower levels of redlining were associated with higher perceived discrimination, which in turn was linked to increased anxiety, depressive symptoms, and perceived stress among Black/African American participants in Detroit..

Despite encouraging findings regarding green spaces promoting lower stroke risk and cardiovascular disease rates, researchers caution that green spaces alone cannot mitigate the health impacts of neighborhood factors like segregation, deprivation, and the enduring effects of discriminatory housing policies. After accounting for these variables, the researchers found that the benefits of living near green spaces diminished.

Several interrelated factors are behind the persistent health disparities including the limited access to healthcare facilities in these neighborhoods. Many historically redlined areas lack adequate health care resources, making it challenging for residents to receive timely and effective care. Economic disadvantage also plays a significant role; lower property values and fewer job opportunities can hinder residents’ ability to afford necessary healthcare services.

Environmental factors further complicate matters. Historically, redlined neighborhoods often grapple with higher levels of pollution and fewer green spaces, which can adversely affect residents’ health. And the chronic stress associated with living in these environments — where discrimination and socioeconomic challenges are rampant — can take a toll on overall well-being.

Redlining has resulted in the residential segregation of Black communities into urban areas, which has heightened vulnerability to extreme heat and poor air quality. Compared to other demographic groups, Black people are 40% more likely to reside in regions with the highest projected increases in extreme temperature-related deaths and 34% more likely to live in areas facing the steepest rise in childhood asthma diagnoses. And Black people are 41% to 60% more likely than non-Black individuals to be located in zones expected to see significant increases in premature deaths linked to harmful particulate matter. This unequal exposure to extreme heat and air pollution significantly raises risk of early mortality.

Access to nutritious food is often limited in redlined communities, contributing to higher rates of obesity and diabetes. Food deserts, characterized by a lack of grocery stores offering fresh produce, compound the health disparities faced by these populations.

These health disparities are not just the result of the immediate environment but are also intertwined with broader systemic issues, including the political and ideological challenges faced by those working to address them. For example, the push for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) research, which seeks to understand and mitigate such inequities, is increasingly under fire.

The Washington Post reported on the challenges faced by researchers in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) within academic institutions. DEI researchers have increasingly been targets of political and ideological attacks, particularly from conservative groups. The backlash has resulted in a chilling effect, leading some academics to alter or abandon their research agendas. There is a clear need for institutions to protect their scholars and ensure that DEI research continues to address systemic inequities.

President Trump’s recent executive orders – signed in January 2025 – have further intensified this issue by directing the termination of all DEI programs across federal agencies and encouraging private sector entities to end their DEI initiatives.

Responsible reporting on health effects of redlining

While statistics are important to understanding the scope of health disparities in redlined neighborhoods, personal stories provide a human face to the numbers. As journalists, we should seek out individuals who can share firsthand experiences of living in historically redlined areas and how those experiences have impacted their health or access to care. Highlighting narratives of resilience and community activism can also shed light on the ways residents are working to overcome these challenges. Pairing this qualitative data with quantitative research — like rates of disease, life expectancy, or health care access — offers a fuller picture of the consequences of redlining.

Additional reporting

- Historical redlining associated with health disparities in children with asthma — Healio.

- Scientists are starting to uncover how neighborhood can affect the biology of cancer — STAT.

- Detroit’s legacy of housing inequity has caused long-term health impacts − these policies can help mitigate that harm — The Conversation.

- How redlining affects biodiversity — PNAS.