Dallas is among cities, counties and other local governments that have recently adopted race equity plans. In the 2022-2023 goals and metrics report, city officials have said they want to track their goals, which include tracking air quality in certain areas and upgrading water and sewer lines in neighborhoods that haven’t seen investment for decades. There’s a line in there about improving the health of the city’s Black and Hispanic residents, who represent more than 60% of the population of the country’s ninth-largest city and are more likely than their white peers to have preventable chronic diseases.

Public entities are increasingly adopting similar goals and measures and hiring executives to make sure they are hitting their marks. As journalists, we must explain to readers how new policies and practices are going to ameliorate the legacy of discriminatory zoning laws, building requirements, and budgetary decisions that may be linked to current health trends by race, ethnicity, educational attainment and other demographic characteristics.

But how do we connect those dots? How often do we keep readers informed about what the city is doing? And do we tackle one government agency at a time? How far back do we go to give stories the appropriate context?

With those questions in mind, I scheduled an interview with James Hardy, a senior program officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Hardy leads the research team that keeps up with housing policies and trends in small and mid-sized cities.

Although reporting on state and federal health equity policies and laws is important, Hardy, a former deputy mayor in Akron, Ohio, argued that journalists should keep up with local ones in part because change can happen a lot quicker at the local level.

He added, “So much of what we want to see in our communities is decided there — as opposed to the state house or Washington, D.C. That’s really where we’re seeing the real innovation as well as the real possibilities for progress.”

Tracking that progress is critical, and I asked Hardy to share some suggestions that could help journalists focus their reporting on equity policies that may influence people’s quality of health. I have included them below along with others that came to mind. You’ll also find a list of resources that can help you give context to your stories.

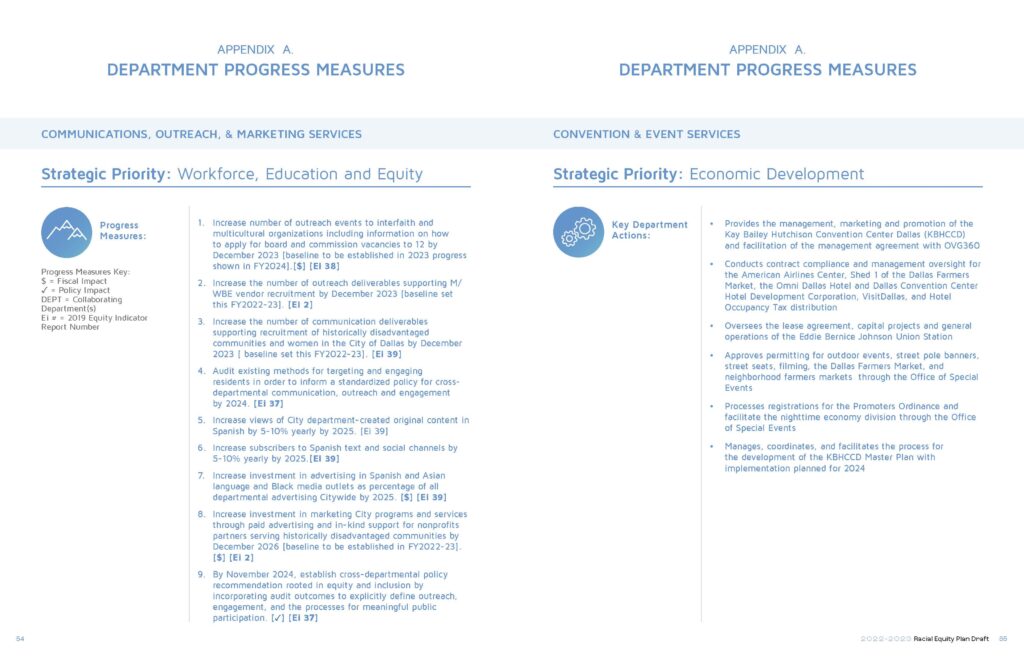

Keeping up with goals

Since Milwaukee officials declared racism a public health crisis in 2018, more than 200 states, cities, school boards and other public entities have made similar statements. Some have passed race equity plans. While all those things are well and good, Hardy said “defining success and resourcing success are the two next steps.”

To find out whether local governments’ equity plans have any teeth, follow the money, Hardy said. Among the data you should look at:

- Health trends in municipalities and counties

- Current and past budgets for infrastructure projects, paying close attention to monies allocated to districts and neighborhoods

- State and federal funding municipalities and counties receive for health departments, beautification projects and public works improvements

- Affordable housing tax incentives

- Historical data about public infrastructure improvements by district and neighborhoods

- What other local governments are doing in municipalities and counties with similarly sized populations in the U.S. and abroad

And Hardy said journalists should ask government officials what their equity measures and milestones are and why they chose them. Thinking of his time in Akron, Hardy said they had some success in defining their achievements, “particularly in the areas of black infant mortality and in economic opportunity.”

“We really tried to push the envelope and worked with not just local but regional leaders in those fields to try and create dashboards that would provide meaningful updates to the community as to where we were at,” added Hardy. “In other ways, we didn’t hit the mark.”

Some of your best sources may be the people living in areas that are getting overdue attention from their governments. Find them at public hearings and at neighborhood association meetings. Academics who study local government policies, civil engineers, environmentalists, and public health experts will offer perspectives to complement what you’re getting from authorities and people on the ground.

Check personal biases

Hardy also had a few things to say about not letting biases get in the way of reporting. News coverage of a street resurfacing program during his time in Akron suggested that journalists are trying to figure out when and how to apply an equity lens to a story, Hardy said.

After a local outlet ran a story suggesting City Hall was shortchanging a neighborhood that had a large concentration of low-income residents and had been neglected by the municipality for years, Hardy said officials met with the journalist who wrote the piece and the managing editor. What the story didn’t say, Hardy said, was that the city had improved the majority of the streets in that area in the preceding two years and that officials were now turning their attention to housing and parks projects and others that needed more investment.

While “we’re not always going to agree” on what the government’s shortcomings are or what it can do differently, Hardy said that experience illustrated that government officials and employees and journalists don’t have to have an adversarial relationship. As a result of the conversation with the reporter and the editor, the outlet published a comprehensive story about the projects the city had completed, the ones that were in the hopper, and the ones that it had fallen short on, he added.

“I’m not saying we don’t need to be pushed” to be held to account, Hardy argued, but reporters should consider “that it still is, in so many ways, a bleeding edge movement in government to be racially and health equity centered.”