Part one of two parts; the second runs tomorrow, Friday, June 11.

You might think that the first new drug to treat Alzheimer’s in 18 years — and the first to treat underlying disease and not just symptoms — would be heralded by patients, families, and medical professionals alike. After all, the FDA’s approval on Monday of aducanumab (brand name Aduhelm) sounds like a tremendous breakthrough for the estimated 6 million Americans, and 50 million people globally, who suffer from the disease.

However, because of the supporting clinical data on its effectiveness, the drug has been controversial from the start. Drug maker Biogen actually halted its parallel Phase 3 studies, ENGAGE and EMERGE, because they failed to meet their primary endpoints. Those original endpoints were a change in the Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), which is similar to a composite endpoint because it assesses improvement in multiple different domains.

A subsequent analysis of data that trickled in from the ENGAGE trial later showed high doses of the drug may actually slow cognitive decline after all. So Biogen did a 180 and applied for accelerated FDA approval last July, as we previously reported.

The FDA’s go-ahead was conditional on the company conducting Phase 4 follow-up studies to monitor for serious reported side effects, including brain swelling and bleeding. The FDA also said the drug could be used for patients at various stages of the disease, not just those with mild cognitive impairment. Patients, Alzheimer’s advocates, and some in the medical community are thrilled.

“Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating illness that can have a profound impact on the lives of people diagnosed with the disease as well as their loved ones,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, M.D., director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in a statement. “Currently available therapies only treat symptoms of the disease; this treatment option is the first therapy to target and affect the underlying disease process of Alzheimer’s. As we have learned from the fight against cancer, the accelerated approval pathway can bring therapies to patients faster while spurring more research and innovation.”

However, other experts, including neurologists, geriatricians, and researchers who diagnose and treat this devastating degenerative disease, say they’re hesitant to prescribe a drug with some very shaky data. The FDA’s decision goes against the advice of some experts on its own advisory committee, including Caleb Alexander, MD, an internist and professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. In an opinion piece in the New York Times on May 28, Alexander and co-author Michael Greicius, a professor of neurology at Stanford and director of the Stanford Center for Memory Disorders, had encouraged the FDA to reject the drug, which will cost about $56,000 per year.

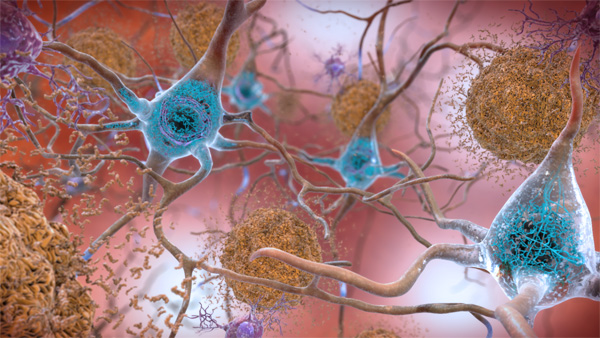

Alexander and Greicius said neither aducanumab nor other experimental drugs that target beta amyloid protein “have demonstrated a convincing effect on slowing progression of the disease.” Beta amyloid protein is a protein that accumulates between neurons from the breakdown of a larger protein, called amyloid precursor protein. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease typically have abnormally high levels of a particular type of beta-amyloid protein that has become a hallmark of the disease.

The link between plaque and AD

Scientists still do not know what causes Alzheimer’s or precisely how it develops, but the current scientific consensus focuses on the beta-amyloid hypothesis, which posits that a major contributor, if not cause, of the disease is the buildup of beta-amyloid plaque in the brain. In fact, presence of this plaque is one of two criteria necessary to diagnose Alzheimer’s. These plaques are scattered all over the brain, and they’re believed to cause toxicity, impair memory and kill nerve cells, as noted by Douglas Scharre, MD, a neurologist and director of the division of Cognitive Neurology at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, who has been involved in clinical trials for aducanumab from the start.

The beta-amyloid hypothesis also suggests that preventing the buildup of beta-amyloid and/or destroying existing beta-amyloid should slow down or prevent the memory loss and overall cognitive decline from Alzheimer’s. The problem is that multiple drugs have been shown to clear the plaque — even confirmed on MRI — without showing any cognitive benefits. Aducanumab, the latest to target the plaque, is a monoclonal antibody that attacks it by binding to it , thereby alerting the immune system to destroy it.

Scharre said the new drug is safe and effective. “These medications are working. We can keep them safe for people. They get rid of these toxic proteins, and it looks like they can potentially change the course of the disease.”

Other Alzheimer’s advocates are more cautious. “Today’s accelerated approval of aducanumab by the FDA, the first new Alzheimer’s drug on the market in nearly two decades, provides hope as another important step in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease. We are hopeful that it will improve the quality of life for individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers. Patient access and affordability to all of those in need is of significant importance,” said the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America in a statement.

Other considerations for the drug

Taking aducanumab isn’t as simple as just popping a pill. The drug must be delivered via infusion, either in a doctor’s office or other clinical setting. The FDA did not restrict which patients could get the drug, even though it was tested on people with mild memory loss, and despite the fact that beta-amyloid plaques typically begin building up in the early stages of the disease. (Aducanumab does not target tau, the other protein plaque characteristic of Alzheimer’s that forms tangles in the brain as the disease progresses.)

Catching Alzheimer’s disease early can be challenging, especially for primary care doctors, who often lack experience or training in early diagnosis. So aducanumab might not work as well as desperate families hope, or even work at all, particularly if the disease has progressed far enough that tau tangles have already begun to form.

Critics of aducanumab have pointed to several other concerns about its approval. For example, the only way to be certain a patient suffers from Alzheimer’s and not another form of dementia requires brain scans. Not only are these scans costly, but Medicare and other insurance plans may not cover them. Cognitive screening could be done in a physician’s office, according to Dilip Jeste, MD, a neuroscientist and director of the Sam and Rose Stein Institute for Research on Aging at UC San Diego. But current screening tools cannot determine whether someone has Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia.

Finally, not everyone with plaque buildup in the brain develops Alzheimer’s, so even if a brain scan could reliably identify plaque buildup, that does not mean aducanumab should be prescribed to them; they may end up taking a drug with potentially serious side effects for a condition they never would have developed.

Most of the scientists who disagree with the FDA’s green light on the drug, including Alexander, have expressed concern that the approval relies only on data from a subset of just two studies. Despite Biogen’s claim that the studies would have met the primary endpoint with a longer follow-up, “this post hoc justification simply cannot replace additional, well-designed, blinded, placebo-controlled randomized trials,” Alexander wrote in May.

“Both sides have strong arguments. So my sense is it doesn’t matter what people think about it, it’s done. What do we do now is the question,” Jeste said in a phone interview. “Physicians, especially primary care providers, need clear guidelines on who and how to recommend this drug.” Jeste hopes specific clinical practice guidelines will be issued very soon. “They need to know who is most likely, or least likely, to be helped by this drug.”