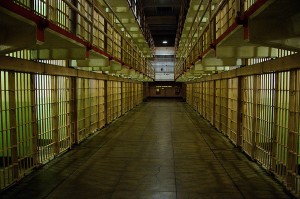

A multi-partisan discussion of criminal justice reform — among Democrats, Republicans and billionaire philanthropists ranging from the libertarian Koch Brothers to the liberal George Soros, who are financing reform efforts — includes the question of what to do about people with mental illnesses who wind up behind bars, including for minor, non-violent offenses.

In its most recent report, released in 2017, the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics reported that 14% of a yearly count of roughly 2.3 million convicted state and federal prisoners and 26% of jailed pre-trial detainees “met the threshold for serious psychological distress.” By comparison, during that same period, mental illness had been diagnosed in 5% of the U.S. population of comparable race, age and gender of those incarcerated persons.

Further, 37% of state and federal prisoners and 44% of jailed, pre-trial detainees had been told by a mental health professional that they had a mental health disorder. In descending order, the most common of those illnesses were

- major depressive disorder.

- bipolar disorder.

- post-traumatic stress or personality disorder.

- schizophrenia or some other psychotic disorder.

Those disorders were reported by 20% of female and 14% of male state and federal prisoners. Additionally, white inmates were more likely than Blacks and Latinx ones to have been told they had a mental disorder.

According to The National Alliance for Mental Illness, those suffering a mental health crisis are more likely to have a run-in with police than to get the medical help they need. And 83% of those with mental illness, NAMI estimates, get no mental health care while jailed, pre-trial. Mental disorders worsen in jails and other correctional facilities, which, nationwide, provide a patchwork of mental health care through a correctional health workforce that often is short on needed psychiatric and other mental health medical staff.

The path to here partly is traced to the 1960s, when institutions for the severely mentally ill were being shuttered. Many deinstitutionalized patients from that era, indeed, were transferred into community-based care that, in some cases, included group homes and other housing, jobs, etc. Many others fell outside of what, then and now, are insufficient safety net services.

The path forward, advocates, say demands a ramping up of several existing avenues and strategies:

- Crisis intervention training for police officers dispatched to calls involving the mentally ill. The Memphis Police Department launched this model in 1988; a few police departments train all, not just some, officers in these practices.

- Crisis-intervention teams that, for example, include social workers and other clinicians who ride-along with police and direct the intervention efforts.

- Mental health treatment courts and other diversion courts, including ones reserved for veterans who, as a group, also suffer more mental and behavioral health problems than the general population. These aim to divert the mentally ill away from incarceration and into services. (Critics of these courts say they don’t always live up to their billing.)