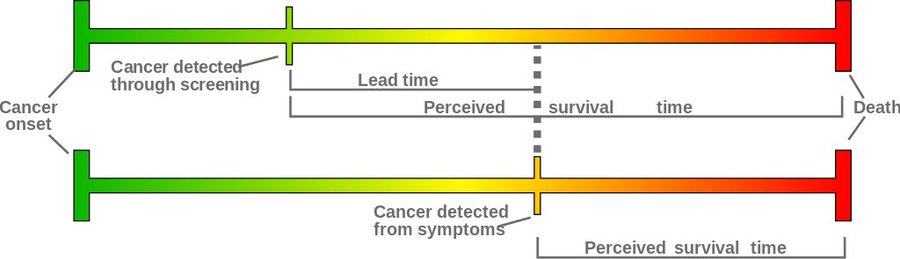

Lead time bias is a well-recognized challenge especially when it comes to studies and statistics looking at cancer screenings. As the entry on the AHCJ website explains, lead time bias is a type of bias that can “artificially inflate the survival time of someone with a disease.”

How? When providers get better at looking for — and finding — a disease, it appears to lengthen the time someone survives after diagnosis. In reality, the patient is not necessarily living longer than they would have if the disease were discovered later. It just seems like they’re living longer because the disease is identified sooner, and the “clock” on survival time starts earlier.

As Abirami Kirubajan, M.D., of the University of Toronto, explains in this YouTube video, “The earlier you diagnose a disease, the longer a patient will appear to survive — even though we just started counting earlier.”

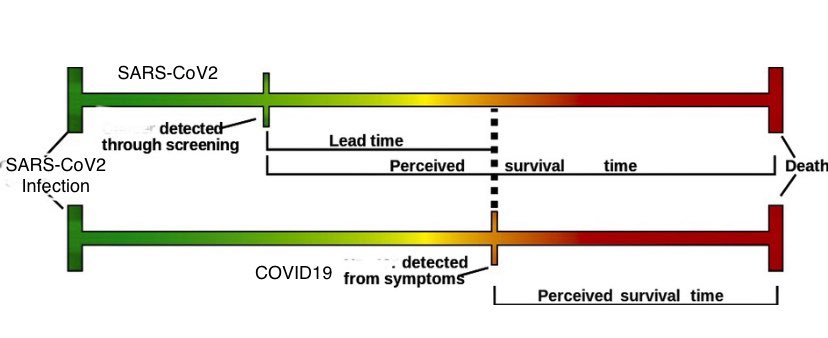

Although lead time bias is most often discussed as a pitfall to watch for when it comes to cancer, it can occur with other diseases too — including COVID-19. Epidemiologist Ellie Murray, Sc.D., an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Health, is a prolific tweeter who frequently uses her platform to teach people to “think like an epidemiologist.”

In a tweetorial from Murray in early July, she described the phenomenon of lead time bias with COVID-19 deaths.

THINK LIKE AN EPIDEMIOLOGIST: why are COVID deaths *still* not going up 3 weeks after case counts started increasing? There are many possible explanations, but one I haven’t seen mentioned is the impact of widespread testing on *early detection*.

A #tweetorial on LEAD TIME BIAS.

— Ellie Murray (@EpiEllie) July 7, 2020

Over 10 tweets, Murray uses fun GIFs and helpful diagrams as she explains how lead time bias can be misleading in comparing the average length of time between a COVID-19 diagnosis and death. She adapts a lead time bias graphic from Wikipedia to illustrate the similarities to this bias with Covid-19:

Then Murray sums up the key point: “When you start identifying people at earlier stages of a disease, it looks like they survive longer (or have the disease longer) compared to when you identify based on severe symptoms.”

That doesn’t mean they actually are. It means we, as journalists, have to consult epidemiologists to understand how to interpret changes in the time between diagnosis and death when we’re reporting on these numbers. It also means we may have to explain these apparent changes — that aren’t really changes — to our readers.