In my corner of Southern California, sewing equipment stores say they’re out of stock on machines priced under $500 because face mask entrepreneurs have gobbled them all up.

As of this weekend, none of the usual suppliers, including Amazon, would ship the quarter-inch elastic, the kind that secures a mask around the ears, at least until late May. Fabric stores are filling online orders with more than a week or two delay in shipping.

Around my ZIP code, which encompasses two major hospitals (and which last week had more than double the number of COVID-19 cases as any other in the county) home-made masks are being smuggled between friends and neighbors like scoring brown bags of really good pot in the early ’70s.

I hunkered over my sewing machine with directions that I found on a credible website, used some fusible cotton interfacing and made myself a pleated mask using hair ties – on the off chance I might ever dare venture out in public again.

But how good are these homemade masks at protecting against spread of coronavirus from being transmitted if an infected person breathes, talks, sneezes or coughs in my vicinity? And if I am infected, how good would the mask I’m wearing succeed in protecting the clerk or friend who leans toward me just a bit too close?

The past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Dr. Daniel Diekema, was eager to answer some of my questions. To my surprise, he wasn’t all that enthused about their usefulness. “Maybe it could be helpful, but I just don’t think the evidence is there for it. So I’m not a huge proponent of mask use in public,” he said.

This goes against the grain, especially in California where public health officials have urged everyone to wear masks when they go outside, which some interpret as a warning that even if they are out alone, or out for a solo walk or a run, they need to wear a face mask lest they get infected when the wind blows toward them the air someone else breathed.

“If you’re going to wear a home-made mask, it should not replace physical distancing, good hand hygiene and the instructions about not touching your face, eyes, nose and mouth,” and, of course, sheltering at home, said Diekema, director of infectious diseases at University of Iowa HealthCare.

Wearing a mask is far less useful than doing those things, he said. More importantly, it could give wearers and those they come in contact with a false sense of security, as if the mask is going to be their salvation.

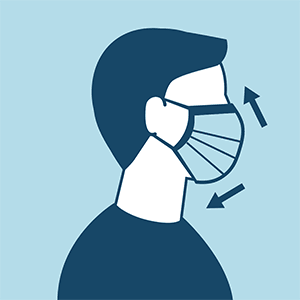

Diekema added that his additional concern is that home-made or improvised masks won’t fit the wearer, and may prompt “people to frequently reach up to adjust their mask or move it, or their face gets warm and they want a little ventilation. That means it brings the hands to the mouth and nose area more often.”

And that “could have the paradoxical effect of increasing the risk of infection.” If you have a properly constructed home-made mask, it probably does filter out the large droplets if you cough, but I think we just don’t know.”

A limited study in a recent issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine by researchers in South Korea also was not reassuring that wearing a mask protects others from virus-laden particles. It found amounts of the virus on the outer surface of the mask, suggesting that the mask was not a complete barrier against someone else getting infected and that a person’s cough would have enough force to penetrate to the other side.

It concluded, “both surgical and cotton masks seem to be ineffective in preventing the dissemination of SARS–CoV-2 from the coughs of patients with COVID-19 to the environment and external mask surface.” However, the study looked at only four patients who each coughed five times into a petri dish about 6.5 inches away.

The World Health Organization also does not recommend that otherwise healthy people wear face masks in public, saying that masks are only needed if a person is taking care of someone with 2019-nCOV infection or if they are coughing or sneezing. The CDC emphasizes that masks “are effective only when used in combination with frequent hand-cleaning with alcohol based hand rub or soap and water.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that people wear cloth face coverings in public settings “where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain (i.e., grocery stores and pharmacies) especially in areas of significant community-based transmission,” but includes a 45-second video of the U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams demonstrating how to make a mask out of cloth.

In the hospital, Diekema said health care workers are allowed to wear masks they bring from home if that’s what they want to do, but they have to put them underneath a face shield, a transparent plastic that covers exposure from below the chin and around the face, and is a more effective barrier against droplets. All health care personnel get those shields to wear.

My AHCJ colleague Tara Haelle wrote an exhaustive piece on this topic April 1 for Forbes and had reasoning similar to Diekema’s. “One of the biggest reasons they won’t protect the average wearer is that most don’t wear them correctly – even when trained – and unconsciously engage in counterproductive behaviors, such as touching the mask frequently,” she wrote.

As Diekema and others have noted, many of the COVID-19 cases seen in the United States and elsewhere appear to be infections occurring within families and close social settings. And while the virus may travel on droplets within aerosols more than six feet, that’s probably not the primary mode of transmission.

Meanwhile, Diekema and others believe that despite the lack of the really good evidence we need, health officials will be recommending people wear masks when they expect to be near other people in public for a long time, “until we’re far along in the downhill slope of the curve,” he said. And that isn’t going to happen anytime soon.