There are still many unknowns about the COVID-19 outbreak, which as of February 26, has sickened more than 81,000 people and killed more than 2,700. See this map to keep up with the figures, which are updated as new information comes in from different countries.

Key questions, such as just how contagious the virus is, how deadly it is and whether there will be widespread transmission outside of China, do not all have precise answers yet. To help answer such questions and others about prevention, the federal public health response, risk factors and similar concerns, the CDC’s COVID-19 FAQ page offers a relatively comprehensive list of questions with succinct answers and links to details.

In situations where there is an evolving outbreak, misinformation also grows. Vox News, on February 20, reported on the host of false stories and hoaxes about the outbreak posted on such platforms as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok. It can be difficult to correct these falsehoods, as shown in a January 2020 study, published in Science Advances, that looked at the conspiracy stories that arose during Zika and yellow outbreaks in Brazil.

To help with coverage, AHCJ on March 10, will host a webcast for members featuring Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, Saskia Popescu, senior infection preventionist at Honor Health, and Maryn McKenna, journalist and infectious disease expert.

In the meantime, we thought it would be helpful for our members to provide a Q&A on covering COVID-19:

Q: As a journalist, what are the resources that I can trust for covering this outbreak?

A: The AHCJ has been compiling a list of trusted resources for journalists here, and we ask members to please send us resources that we may have missed. Bara Vaida has also created a curated Twitter list of trusted experts and reporters covering the outbreak.

Q: What is COVID-19?

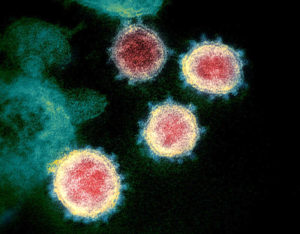

A: It is a disease caused by a type of virus called a coronavirus, which appears to have a halo or corona when seen under an electron microscope. Coronaviruses commonly circulate among humans and usually result in no or mild illness like a cold. Some like COVID-19 cause much more serious illness and potentially death. Two other coronaviruses that can cause serious illness include severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), but COVID-19 is distinct from these.

This most recent coronavirus-caused disease was named COVID-19 by the World Health Organization on February 11. The ‘co’ stands for coronavirus, ‘vi’ stands for virus, and ‘d’ stands for disease, which first emerged in 2019.

Q: Where can I see maps of where transmission is occurring?

A: Several sites feature maps that are tracking the outbreak globally. Johns Hopkins University maintains a relatively robust interactive map for tracking cumulative and current cases across the world. It is based on data aggregated from the CDC and other public health sources globally. Another interactive map by University of Washington geographer Bo Zhao adjusts the numbers and graphs based on the geographic area the user selects. EpidemicTracker tracks COVID-19 along with any other current outbreaks. Several publications are maintaining maps, including The New York Times and Asian Review.

Q: How does it spread?

A: It spreads between people through respiratory droplets from coughing, sneezing and personal contact with an infected person (defined as being within 6 feet of the person.) There is evidence that the virus can live on surfaces for several hours. That means a person can infect themselves by touching an infected surface, then the mouth, nose, eyes and fecal contamination. People are thought to be most contagious when demonstrating flu-like symptoms, which include cough, fever, fatigue and difficulty breathing. There have been a few reports that people can be contagious without symptoms, but there isn’t clarity yet on whether this is correct.

Q: What is the origin of the virus causing COVID-19?

A: Scientists have not yet determined where the virus originated, such as from human contact with an animal like a pangolin or snake.

Q: How infectious is it?

A: Epidemiologists use a term for explaining the average number of people an infected person will spread their illness to, called the ‘r-naught’ number (the ‘r’ stands for reproduction’). The ‘r-naught’ number for COVID-19 has been estimated to range from between two to three. In comparison, the range for measles is 12 to 18.

However, the ‘r-naught’ figure isn’t fixed, and it’s especially likely to be fluid this early in the outbreak. That’s because data collection about cases and both local and worldwide surveillance are unreliable. As surveillance methods and data improves, the number will gradually become more stable, but still could change as people develop immunity and avoid sick people, and as public health officials determine and implement best practices to reduce transmission. Also, some people may be more contagious than others. Some reports of “super-spreaders” suggest there are infected individuals who have spread COVID-19 to more than 2 or 3 people, but scientists don’t know yet whether this is correct. The upshot is that the ‘r-naught’ figure isn’t yet certain, and should be discussed with caution and caveats.

Q: How deadly is it?

A: Just as current surveillance and data collection challenges can affect our understanding of infectiousness, so too do those challenges affect accurate calculations about mortality. Based on the data provided by China, the mortality rate is estimated at around 2 percent, but the rate may be much lower because many people may have been infected but do not show symptoms or are only mildly ill and therefore go unreported. For comparison, influenza has a mortality rate of about 0.1 percent to 0.2 percent.

Q: How long is the period between someone becoming infected with COVID-19 and the person getting sick?

A: According to February 14 statements by CDC’s head of vaccine and respiratory diseases center, Nancy Messonnier, the incubation period lasts up to 14 days. Someone exposed to the virus may not show symptoms for many days and may have negative test results but later be shown to be infected. The reason is that it takes the virus more time to replicate in some bodies than in others.

Q: How bad could this outbreak become?

A: This is unknown. Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said on February 17 that “we are going to know in the next month or so what direction this is going.”

Q: Will warmer weather in the spring affect the transmission of the disease?

A: While many viruses are seasonal and primarily circulate only certain times of the year (such as influenza or rotavirus), it’s not yet clear whether COVID-19 is similar. It is possible transmission will slow as the weather warms up, but it’s also possible the weather will have no appreciable effect on transmission or infection rate. Right now, researchers lack sufficient data.

Q: Will COVID-19 become widespread in the U.S.?

A: This is unknown. As of February 24, there were 15 cases in the U.S involving people who had traveled to the epicenter of the outbreak in China or were living with another infected person. The CDC, so far, has tested at least 426 people for the virus.

At a February 25 press briefing, CDC deputy director Anne Schuchat said that the risk to U.S. citizens currently is low, but that the public should prepare for the possibility of a sustained spread in this country. At another press briefing that day, the CDC’s Messonnier also said that it was not a question of “if” but “when” there will be community spread of the virus in the U.S. Here is a link to the audio and transcript of that briefing.

In an excellent piece at The Atlantic, journalist James Hamblin lays out the reasons a spread in the U.S. is likely.

Dr. Scott Gottlieb, a former FDA chairman, testified to the U.S. Senate on February 12 that he believes there already is an undetected spread of COVID-19 in the U.S., and more cases will emerge in the next few weeks. So far, there isn’t evidence that there has been much undetected spread. See this February 21 study looking at current U.S. flu data.

The CDC has said five public health labs — Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle — were to have begun testing for the COVID-19 virus in cases where a sick person tested negative for influenza, but a faulty CDC test has delayed its broader implementation. Currently, U.S. border patrol and some hospital systems are only testing people who recently returned from China.

Q: Who should be tested for COVID-19?

A: Right now, there isn’t a diagnostic test available for widespread testing. If someone recently has traveled to a location with an ongoing COVID-19 outbreak and later develops flu-like symptoms, they should check with their health provider.

Q: Are there any treatments or vaccines?

A: Not yet. Trials of two drug therapies involving antivirals have begun in China, with early results may be available in three weeks. The U.S. has partnered with Sanofi Pasteur to develop a vaccine and Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen Pharmaceuticals unit to develop therapeutics. The National Institutes of Health has begun testing an antiviral called remdesivir to determine whether it effectively treats COVID-19. It likely will take many months to at least a year before medical countermeasures against the disease will be available.

Q: How can people best prepare for the potential of sustained transmission in the U.S.?

A: The CDC, on February 25, released a framework for how it will respond to the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S., and what citizens and individuals should consider if this situation occurs. Some of the recommendations include people getting the flu shot and doing whatever they can to prevent the spread of any disease by washing hands frequently and staying home if they feel ill. An influenza infection reduces a person’s immune defenses, which increases the likelihood of infection by other pathogens they encounter. Healthcare providers should be on alert for any sick patients who recently traveled to China.

If there should be a widespread transmission of the virus, the CDC said to expect the possibility of school closures and other social distancing measures, such as cancellation of mass gatherings.

King County in Washington state developed a pandemic planning checklist for items to stock up on at home for the unlikely scenario in which people must remain in their homes due to a widespread outbreak. The New York Times has a list of suggestions on what to do to prepare. It includes washing your hands, keeping a good supply of essential medications and getting a flu shot.

Q: Does Lysol or Clorox kill the virus?

A: These products have been shown to kill other coronaviruses, and probably can kill the virus that causes COVID-19, but there haven’t yet been any scientific tests done to confirm this. Also, remember that these products are meant to be used on household surfaces, not people’s bodies.

Q: Should people get a face mask? Should they be wearing one?

A: The CDC isn’t recommending it. If someone is actively sick, wearing one may help stop the spread of infection, but face masks can only do so much, and price gouging already is a problem.

Q: Was this outbreak caused by a bioterrorism lab in Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak?

A: Scientists say no. This claim is based on an unpublished and dubious scientific paper written by Indian scientists that dozens of researchers have said is flawed. The paper was withdrawn from publication after the flaws were pointed out.

Q: Are there any specific known risk factors for developing an infection or for its severity?

A: The primary risk factor known at present is simply exposure to the illness. Beyond that, scientists do not yet have enough information to determine what factors contribute to the severity of the symptoms or what factors might mitigate them. People’s immune systems vary in general, and it’s not possible to predict how all immune systems will respond to a novel virus. However, anyone with a weakened immune system and those who are elderly — since a person’s immune system becomes less efficient with age — are likely to be at a greater risk for more severe infections.

Q: Is there any risk of COVID-19 infection associated with Chinese restaurants, Chinatowns, or Chinese-related cultural events?

A: There is no evidence to suggest that the risk of infection is higher at or near restaurants, events or schools related to the Chinese culture. A bigger problem at the moment is stigma and prejudice toward Chinese cultural activities and locations.

Q: Should I be concerned about travel?

A: Check this CDC site to see updated travel information.