It’s well recognized that health care costs more in the United States than anywhere else in the world. There are myriad of complex reasons, but one aspect of health care costs that often gets lost in the conversation is how much Americans are paying for services they don’t need. Overuse of antibiotics is an often go-to example of this, but it happens with screening tests as well, especially when guidelines aren’t clear or are frequently evolving.

A recent study in JAMA Internal Medicine highlighted an excellent example of patients receiving interventions they don’t need, cost money and can cause harm. Studies like these are worth reporting on their own, but also can inspire larger stories that go deeper or look more broadly at a particular field, geographic region or population of patients. (Disclosure: I reported on this particular study for a news publication.)

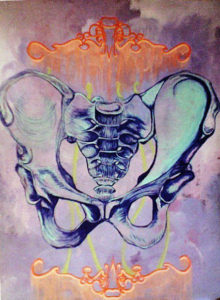

The study focused on bimanual pelvic exams and Pap screening tests in adolescents and young women aged 15-20. (Note: While transgender men also may receive these unnecessary interventions, I’ve used the term “women” here because the study appears to involve only self-identifying females.)

Bimanual pelvic exams involve the insertion of two fingers to palpate internal organs, usually with the use of a speculum. These exams are uncomfortable and invasive. Though previously recommended annually during women’s health preventive visits, they are now only recommended by medical organizations in pregnant women and those getting an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD), receiving treatment for a sexually transmitted infection (STI) or experiencing another medical problem.

The study found that 23 percent of females aged 15-20 had received a pelvic exam in the past year. More than half of these were probably not medically indicated per current guidelines, the authors concluded.

Similarly, Pap tests — used to screen for cervical cancer — are not recommended in women under age 21 except those who are HIV positive and sexually active. Yet one in five patients in the study had received a Pap test in the past year — and about 72 percent probably weren’t needed.

Not surprisingly, the researchers found a strong correlation between receiving both unnecessary interventions: those who had a Pap test were seven times more likely to have a pelvic exam too. (Nearly all the unnecessary exams and Pap tests were at the same visit.)

One obvious problem with all these unnecessary tests is their cost. Another is wasted time and other resources. But for patients, perhaps the biggest problem is their potential for harm.

In a JAMA Internal Medicine editorial, Melissa A. Simon, M.D., M.P.H., who is an OB-GYN at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, noted a commonly repeated excuse for promoting routine pelvic exams despite the guidelines: that it might encourage women to see their doctor at least once a year. But as she quickly adds, there’s no evidence to back up that assertion.

“In fact, many women (younger and older) associate the bimanual pelvic and speculum examinations with fear, anxiety, embarrassment, discomfort, and pain,” she writes, and those “with a history of sexual violence may be more vulnerable to these harms.”

Further, screenings often aren’t recommended for certain populations because of the risk of false positives, which nearly always leads to anxiety and more invasive testing often with other increasing risks, such as infection during a biopsy. Screenings are only recommended when the potential benefit outweighs the potential harm.

Simon describes another possible unintended consequence of routinely using an invasive procedure when not indicated: teens might delay starting contraception or getting STI testing done because of fear or anxiety about getting a pelvic exam. As a former teenage girl and a former high school teacher of them, I can attest to that likelihood.

Simon notes that doctors often fall into familiar routines and haven’t necessarily been taught how to “unlearn” a practice. Journalists can help the “unlearning” process by reporting on unnecessary interventions that can cause harm, especially if the story includes personal stories of people harmed by the interventions.

A study like this also can be a jumping-off place for a broader piece on other practices in gynecology are unnecessary and over-used. For journalists wanting to pursue stories like these, the Choosing Wisely campaign — which seeks to reduce unnecessary care — is a great place to start.