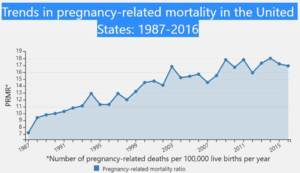

For the past several years, health care journalists have correctly focused on the rising rate of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States. Data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that over the past 40 years, the nation’s rate of pregnancy-related deaths has more than doubled.

Although the rate dropped slightly in 2016 to 16.9 per 100,000 live births (from a high of 18 in 2014), the rate was 7.2 per 100,000 in 1987 when the CDC began tracking the data.

Note that the CDC defines pregnancy-related deaths as the death of a woman while pregnant or within a year of the end of a pregnancy.

One of the most overlooked statistics in the debate about how to reduce these deaths (also called maternal mortality), is that the highest rate of deaths in this category is among black women, a fact that Andrea King Collier points out in a new tip sheet.

An author and freelance health care journalist in Lansing, Mich., Collier writes about family issues, illness prevention, women’s health and end-of-life.

She explains that for every 100,000 live births, some 11.4 Latinx women die every year and 13 white women die annually. “Yet the number jumps for black women to 42.8 for every 100,000 live births,” Collier writes. That’s 3.3 times higher than the rate for white women.

For health care journalists, Collier adds that experts in maternal mortality agree that 60% of these deaths are preventable. So, what will it take for the United States to drop the death rate for all mothers and particularly for black women?

In her tip sheet, Collier focuses on the need for health care policy and payment reform, writing that last year, Congress passed the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act (HR 1318) to fund state efforts to investigate pregnancy-related deaths.

One of the sources she cites was an article in The Health Affairs blog that explained the law and how it calls on states to establish Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs). These committees would be a great resource for journalists seeking to localize their stories on the state or regional level, she adds.

She also reports on efforts to reform payment models, explaining that the current payment systems fail to cover high-value services adequately, do not hold providers accountable for overall costs and outcomes and do not encourage coordination among providers.

We’ve covered the need for pregnancy-related payment reform in two previous tip sheets. One was earlier this year, “How payment reform could help the U.S. reduce its high C-section rate,” and the other one was last year, “In maternity care, hospitals know what to do, but most fail to do it.”

Data from the CDC shows the considerable racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related mortality exist. During 2011–2016, the pregnancy-related mortality ratios were:

- 42.4 deaths per 100,000 live births for black non-Hispanic women.

- 30.4 deaths per 100,000 live births for American Indian/Alaskan Native non-Hispanic women.

- 14.1 deaths per 100,000 live births for Asian/Pacific Islander non-Hispanic women.

- 13.0 deaths per 100,000 live births for white non-Hispanic women.

- 11.3 deaths per 100,000 live births for Hispanic women.