Researchers are looking to old drugs, plants and viruses in a race to find new ways to kill disease-causing microbes before they become resistant to all existing pharmaceuticals, but their work will flounder if the federal government can’t figure out how to incentive companies to turn their work into commercially viable drugs.

That’s what antimicrobial resistance experts, many of whom are working on developing new tools to fight microbes, told attendees of the Health Journalism 2019 panel “A Future Without Antibiotics,” moderated by journalist Maryn McKenna.

“The economic market is a huge concern,” said panelist Cassandra Quave, assistant professor of dermatology and human health at Emory University. “My personal opinion is that it will be the military that will drive forward the future of antibiotic production. … I don’t know how else unless the government intercedes.”

The problem of “superbugs” – microbes that have become resistant to antimicrobial drugs – has been growing exponentially and if nothing changes, as many as 10 million people may die annually around the world by 2050, according to the World Bank. Already, at least 23,000 people are dying in the U.S. each year, as a result of contracting a resistant bug, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since antibiotics were widely introduced in the late 1940’s, medical experts have warned of bacteria’s innate ability to evolve and develop resistance. Until the past two decades however, pharmaceutical companies kept developing new antibiotics to stay ahead of that resistance.

Today, just a handful of large drug companies are spending money on developing new antimicrobials. The reason is that the return on investment is low. Antibiotics are used for just a few days, unlike drugs for chronic diseases, which may be needed for a lifetime.

The commercial market has become so poor for antibiotics that even companies that have successfully developed a new antibiotic can’t stay in business. Most recently, biopharmaceutical firm Achaogen, which spent years and millions of dollars successfully developing plazomicin, an antibiotic to treat resistant urinary tract infections, filed for bankruptcy in April 2019. The Food and Drug Administration had approved plazomicin for the U.S. market in June of 2018.

“There have basically been zero new drugs since the 1980’s,” said panelist Lori L. Burrows, professor of biochemistry and associate director of partnerships and outreach at McMaster University’s Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research. “The one new drug that was approved last summer went bankrupt. That is terrifying. The [drugs] that we have, when they stop working, there aren’t any more. When they [become] resistant [to existing antibiotics], we don’t have any more to treat you.”

Many health leaders are aware of the dire situation for new antibiotics, which is why numerous business and health experts have been working on developing policy solutions to fix the antibiotics market.

Panelist Anthony D. So, professor of practice, director of IDEA Initiative Innovation Design Enabling Access and director of the strategic policy program ReACT – Action on Antibiotics at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, is one of those leaders. He is working on policies that would both support early-stage research in new antibiotics, as well as ways to guarantee drug companies income to make it worth their while to invest in developing new antimicrobials.

“There is a history of” the government getting involved in antibiotic development, So said. He added that the U.S. government provided initial seed money that enabled the creation of penicillin in the 1940s. Then, the military contracted to purchase the drugs to treat soldiers during World War II and thereafter, enabling the antibiotics market to flourish.

“We will probably need to have a concerted effort again” by the government, So said.

Meanwhile, Quave and Burrows outlined their research to find new compounds to treat resistant microbes.

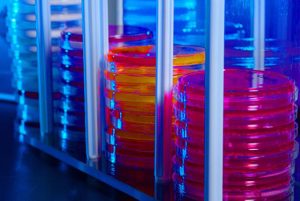

Burrows’ research team is studying biofilms, a term for the way that bacteria grow into colonies and then protect one another from outside threats. By experimenting with combinations of common and old drugs, researchers have found ways to disrupt these colonies, suggesting ways to develop new antimicrobials. Quave’s researchers have been scouring the world for botanical sources of antimicrobials and have found several promising candidates.

Panelist Alexander Sulakvelidze, executive vice president and chief scientific officer at Interlytix Inc., explained how his firm is harnessing phages, the term for types of viruses that specifically kill bacteria, including those that are resistant to antibiotics.

For more on antimicrobial resistance, click here for AHCJ’s tip sheet on covering this topic and here for covering the business challenges in the market.