In three years, prescriptions for a new class of weight loss drugs (called GLP-1 receptor agonists) have been so robust that they rank among the top-selling medications in Medicare’s prescription-drug program, according to a new report from KFF.

The report, “Medicare Spending on Ozempic and Other GLP-1s Is Skyrocketing,” shows that medications like such as Ozempic and Mounjaro were developed to treat patients with type 2 diabetes. A third GLP-1, Wegovy, gained FDA approval in 2021 for chronic weight management for adults who are obese or overweight and had another weight-related condition (such as high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, or high cholesterol). Then on March 8 of this year, the FDA approved a new use for Wegovy, to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, heart attack and stroke in obese or overweight adults with heart disease.

Since the drugs gained FDA approval, patients with diabetes who took them have lost weight, driving up demand, even though weight loss is an off-label use, as Kristen Monaco reported for MedPage Today in November. While Medicare will not pay for the use of GLP-1s for weight loss, commercial health plans do so, as do standalone Medicare Part D plans and employers.

Stories to pursue

For journalists, this story is significant because these drugs have a list price of more than $1,000 a month. This is a factor that could ripple through the health care system by driving up drug costs and health insurance premiums for everyone and for Medicare Part D, the federal prescription drug program, as Peter Loftus reported for The Wall Street Journal on March 21.

The KFF report noted that the combination of consumer demand for GLP-1s, new uses and the high prices for these medications, could cause Medicare spending to rise and health insurers to raise the premiums they charge for Part D plans.

The high prices are already causing employers to cut back on spending for these drugs as demand drives up costs, reported Jennifer Calfas for the journal on March 5. Wegovy and another GLP-1, Zepbound, are so popular that the manufacturers cannot meet the demand, she wrote.

Soaring federal costs

The KFF report shows that over five years, gross sales for just three GLP-1 drugs that Medicare covers (Ozempic, Rybelsus and Mounjaro) went from almost $57 million in 2018 to $5.7 billion in 2022. Reporters should note that gross spending does not account for rebates from manufacturers that lower net spending. Even with rebates from pharmaceutical companies, covering these drugs still costs billions of dollars, Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of KFF’s program on Medicare policy, said in an interview.

In one year (2021 to 2022) gross Medicare spending for Ozempic alone nearly doubled — from $2.6 billion to $4.6 billion in 2022. That put Ozempic in sixth place among the top-selling drugs in Medicare Part D that year, up from 10th place in 2021.

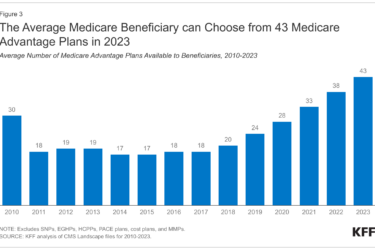

In November, a separate KFF report showed that monthly premiums for drug coverage are five times higher on average this year over what members paid last year for stand-alone prescription drug plans compared with Part D plans affiliated with Medicare Advantage plans.

Prevalence of diabetes and obesity

Another story angle to consider is the prevalence of diabetes and the effect GLP-1s could have on that population. These drugs are now approved for Medicare members with prescription drug plans only for the treatment of diabetes, and in the case of Wegovy, to help prevent or mitigate cardiovascular disease. Among the Medicare population, the prevalence of diabetes continues to rise. Almost three in 10 (29.2%) older people were estimated to have the disease in 2021, according to the American Diabetes Association.

In addition to helping to control diabetes, GLP-1s can promote weight loss, including two that the FDA approved for this indication: Ozempic and Zepbound). Roughly four in 10 people of all ages (41.9% in 2017) are considered obese (having a BMI of more than 30), making obesity one of the nation’s most prevalent conditions. Among adults 60 and older, the obesity prevalence was 41.5% according to the CDC. The estimated annual medical cost of obesity in the United States was nearly $173 billion in 2019. Medical costs for adults who had obesity were $1,861 higher than for people with healthy weight.

People who are overweight are more likely to suffer from high blood pressure, high levels of blood fats, diabetes and LDL cholesterol — all risk factors for heart disease and stroke.

Among certain populations, rates of obesity and diabetes are both higher. Here’s the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity among all age groups:

- Non-Hispanic Black adults: 49.9%.

- African American women have the highest rates of obesity or being overweight compared with other groups in the United States. About four out of five African American women are overweight or obese.

- Hispanic adults: 45.6%.

- Non-Hispanic White adults: 41.4%.

- Non-Hispanic Asian adults: 16.1%.

The coverage question

Despite the prevalence of diabetes and obesity, it’s difficult for many people to afford these drugs without insurance coverage. For older people who live on fixed incomes, it is nearly impossible, Cubanski warned.

“Based on the list price of these medications, they’re unaffordable for most people who don’t have coverage for them,” she explained. “Certainly, most people on Medicare don’t have the resources to spend $10,000 or $12,000 a year on an obesity drug, or any drug for that matter.”

New research showing the cost to manufacture these medications ranges from less than $1 to about $74, which raises an important question for journalists to ask the manufacturers: Why are the list prices so high?

Why aren’t obesity drugs covered?

And, here’s a question journalists can ask health insurers: If these weight loss drugs were approved for older, overweight or obese beneficiaries, could they reduce the risk of serious complications or at least improve health outcomes and lower health care costs?

There’s little hard evidence about potential cost savings from covering these anti-obesity medications, Cubanski noted.

“I don’t think we’ve seen those pieces all put together neatly in a way that suggests that health care costs will decline so significantly, that that will offset the higher costs that we will certainly incur by covering these medications, because they’re expensive,” she said.

Under federal law, Medicare is prohibited from covering these drugs as weight loss medications. Also, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) would need to score any new legislation, and is looking for evidence to suggest that the magnitude of potential savings from covering these medications over 10 or 20 years or more, would result in savings.

In a CBO report in March, principal analyst Noelia Duchovny wrote, “CBO expects that at their current prices, [anti-obesity medications] would cost the federal government more than it would save from reducing other health care spending — which would lead to an overall increase in the deficit over the next 10 years.”

Another question is whether these drugs may have significant long-term adverse effects. Ozempic was approved in late 2017, Rybelsus in 2019, Wegovy in 2021 and Mounjaro in 2022.

“There are concerns that these drugs have side effects,” said Cubanski.

Long-term studies on older adults are needed because they often contend with other chronic conditions and take other medications that might affect efficacy or make it hard for patients to stay on them. Potential unintended consequences include the risk of falls among older adults who could lose muscle along with fat.

“There’s just a lot more that would be good to know before we just take the brakes off and allow for widespread coverage,” Cubanski explained. “It’s important to proceed with caution. And, at the same time, recognize that many people are getting substantial benefit from these medications. How we balance that is a really important discussion.”

Resources

- The Federal Perspective on Coverage of Medications to Treat Obesity: Considerations From the Congressional Budget Office, March 20, 2024.

- Estimated Sustainable Cost-Based Prices for Diabetes Medicines, JAMA Network Open, March 27.

- FDA approves Wegovy for adults with serious heart problems, press release, March 8, 2024.

- Medical Costs Associated With Diabetes Complications in Medicare Beneficiaries Aged 65 Years or Older With Type 2 Diabetes, Diabetes Care, 2022.

- Adult Obesity Facts, CDC.