I’ve covered health for a long time, as a writer and editor. This year, I’ve started reporting more on climate and health, which had not been my prior focus. Developing story ideas hasn’t been a problem. But developing sources — at a time when the White House is calling climate change a hoax, when universities and research institutes are losing grants, when many experts are in a duck-and-cover mode — has at times been challenging in ways that I’m not accustomed to.

Usually health policy experts in the public sphere, particularly those in government or advocacy, are pretty chatty. They want to boost their ideas (and when the topic is political, as so much of health is, shoot down those of the other side). Academics and researchers are usually pleased when a reporter reaches out, hoping to amplify their work. But given how politicized both public health and climate change are now, that’s not always the case.

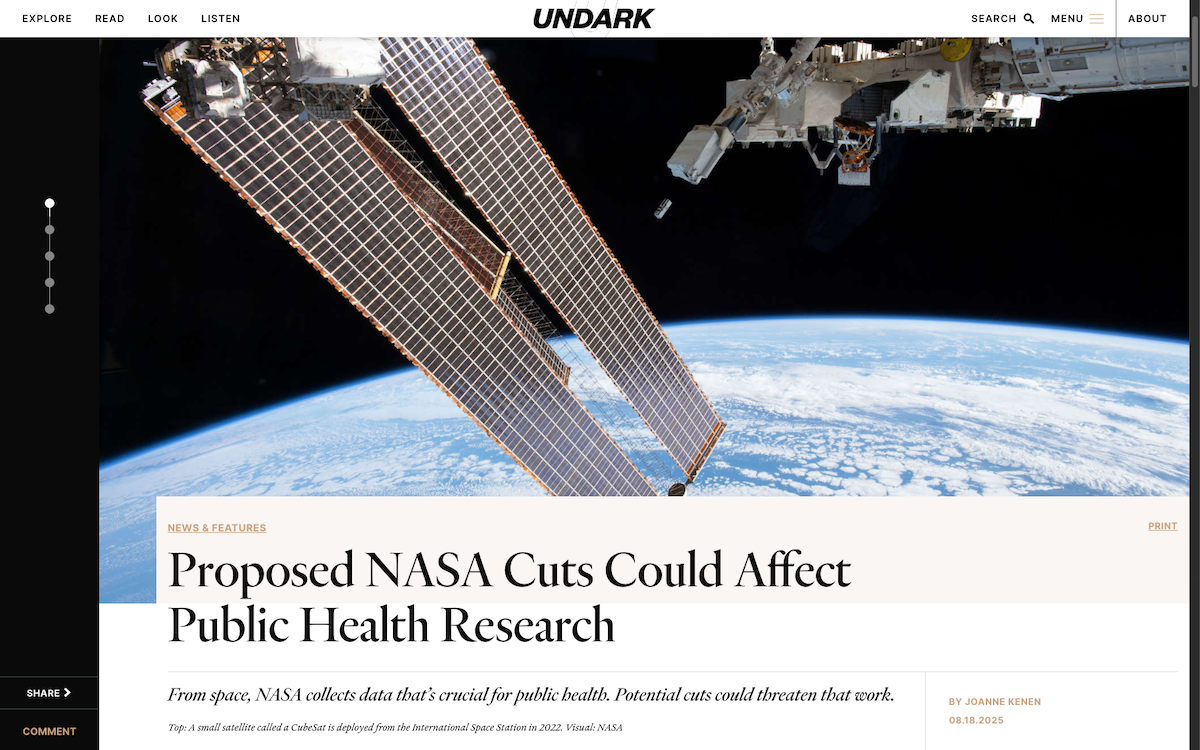

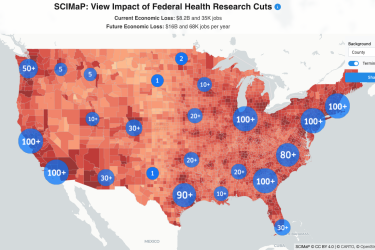

The first big story I took on, for Undark, was about NASA. I had learned at a public health conference that NASA was the source of an enormous amount of climate data — 25 terabytes collected every day — that scientists and public health officials in the U.S. and around the world had relied on. This was news to me. NASA isn’t a public health agency, of course — but it sort of is, working on all sorts of diseases and conditions in the U.S. and globally related to the environment.

The panel I attended wasn’t about NASA per se. It was a climate and public health mashup. But there was a top NASA scientist there, a meteorologist named John Haynes, and he was fascinating — but I was told the panel was off the record. (This was about eight weeks or so into the Trump administration; I can name Haynes here because he was listed on the public program as a speaker). But I introduced myself after his talk, said I wanted to write about NASA and health, and could I use his comments on the record or arrange a follow-up conversation. He declined. I had his email — it was on his PowerPoint — but when I asked him for an alternative way to reach him in case NASA’s budget was cut, he told me that wouldn’t be necessary, that the work email would be fine. I was skeptical; this was March 2025, and DOGE was in full flower.

Since this was new to me, and no one had written much for the general public about the breadth of NASA’s climate work, I did a lot of background reading before I pitched the story. I downloaded lots of material from the NASA website, fearing it would vanish like so much other government information. The Trump administration soon proposed deep cuts to NASA’s budget, including Earth Science. I reached out to Haynes and other NASA scientists whose work I was reading. Not one responded. NASA press officers were not responsive, other than a bland last-minute comment before I closed out the story.

I had expected this story to take me a few weeks. It was closer to three months from start to the final edit. One reason was because I had a learning curve. Another was because, although some scientists and public health experts at universities who had worked with or been funded by NASA were happy to talk (some more than once), a surprising number ignored me, reluctant to draw attention to themselves when climate research had become so toxic and funding so fragile.

To fill in gaps, I began tracking down researchers whose names appeared on the NASA PowerPoints I had downloaded. The slides were undated and jumbled. To figure out who was still at NASA, who was at a university and whether they were still at that same university, I googled, emailed, checked Google Scholar, and university websites. It was tedious. (A few times, when a potential source wasn’t where I expected them to be and I couldn’t find them elsewhere, I searched online obituaries.)

Once, I emailed a scientist still at NASA and said something like, “I understand you cannot talk to me at this moment in time. But I came across an interesting project about dust storms and respiratory health you did with the Albuquerque school system, but the NASA materials are undated and the current spokesman for the schools isn’t aware of it. Could you at least tell me the name of the non-NASA expert you worked with there?”

No response.

Yet I found ways to include their voices, or at least their expertise. In addition to reading NASA materials and journal articles, in the public domain, I found some of these experts on Youtube — both some local TV hits and NASA’s own recordings and streams. That let me use direct quotations from Haynes and others. (I was careful to specify the dates of these quotes, as they were several months old.)

Since NASA collaborated a lot with the CDC, I also tried that agency, which initially ignored my queries. Through LinkedIn and some sources I already had, I connected to some former CDC officials for background, and managed to reach some current ones who wouldn’t talk themselves without authorization under the new administration but promised to get the press office to reach out. I finally did get a query from the press people. But after I sent them the note they requested explaining what I was working on and what information I needed, more silence.

The editor I was working with reminded me I could tap the Hill. Democrats on the House Science Committee responded; Republicans did not, although I found on-the-record statements on their websites and I watched recorded snippets of hearings. OMB budget documents were also public. Finally, I could write my story.