This story is the first in a four–part series. The next article will look at the history and background of bird flu, including H5N1 and provide key resources for reporting on this topic.

It was challenging enough to cover the COVID-19 pandemic in real-time as it developed, but how do you cover an almost-it-could-happen-but-we-don’t-know-yet pandemic that might or might not ever come to fruition? That is the challenge health journalists face with the ongoing bird flu situation — highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). If you have been struggling to determine how best to follow and cover the ongoing, unfolding events of avian influenza, we’ll provide some tips and resources to help.

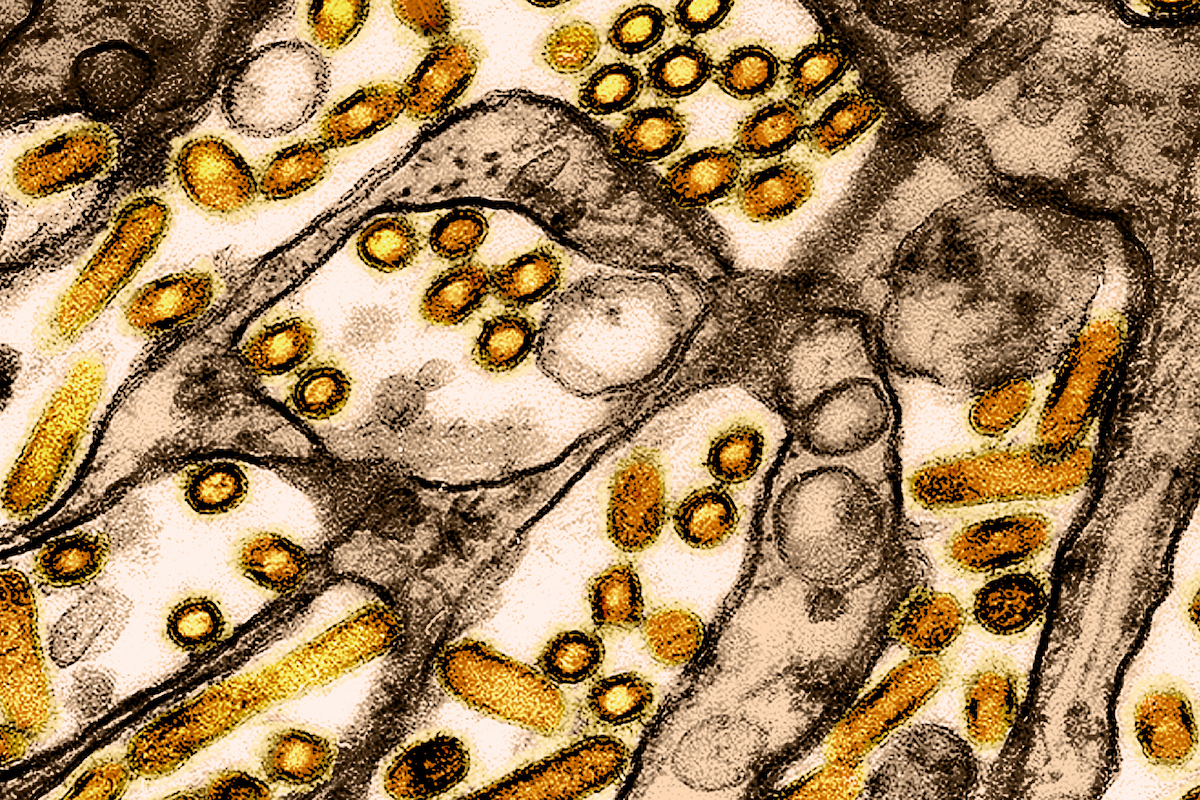

We don’t know if the bird flu outbreak currently in dairy cows and poultry flocks will “jump” into humans and cause an influenza pandemic. Right now, there is no reliable way to predict the likelihood of that. Although 70 people, as of May 2025, have been infected with H5N1 avian flu, all these cases were transmitted by animals and did not result in human-to-human transmission. Hence the CDC’s current assessment that risk to the public is low.

The virus would have to mutate to achieve human-to-human transmission to allow for a pandemic. Even then, the possibility of a pandemic developing from human-to-human transmission depends on multiple factors, such as the virulence and course of the disease in humans, the basic reproduction number, local and national response to a detected outbreak, and so on.

But here is the bottom line: This strain of H5N1 is here to stay, it’s evolving, and we don’t have the information we need to catch bird flu early if it spreads human-to-human. It is already having economic effects and has killed pets and one person — and more stories need to be told.

“This is the largest animal disease outbreak we’ve ever had,” Maurice Pitesky, veterinary researcher at the University of California Davis (who will be on the bird flu panel at AHCJ’s annual conference in May), told Knowable Magazine in April.

And it has the potential to become much more. Local journalists in particular are frontline soldiers and need to be on the lookout for effects that may not be caught by state and national public health and agriculture agencies reeling from cuts and, often, the inability to release information.

Over the next week, we’ll provide several tip sheets to outline the big picture with bird flu, what stories need coverage, how to seek out undercovered stories, and where to find essential data.

What to know about H5N1 in humans

Though the risk to humans overall remains low, as the CDC and WHO have stated, the risk is low to moderate for workers who have contact with infected animals, and the overall risk to humans could change without warning. For a long time, it wasn’t thought that H5N1 could easily leap into humans, or that it would not have much of an effect if it did.

But that’s exactly what happened in Hong Kong in 1997, when it killed a 3-year-old boy and five others. That was the first evidence that bird flu could cross into humans without an intermediate step in a pig or other mammal. Though that specific strain was killed off, its parent strain spread, kicking off a global event well-described in Amber Dance’s excellent piece at Knowable.

That incident also underscored how little we understand this family of viruses and what they’re capable of. It also hints at how ill-prepared we may be for another pandemic, particularly since we cannot assume a bird flu pandemic in humans would pan out the way the COVID-19 pandemic did. Plenty of reflection has been examining mistakes made during the pandemic, some of which arose from assumptions based on past pandemics, such as SARS, the 2009-2010 H1N1 flu and the 1918-1919 flu.

Another pandemic?

Each pandemic is different, and journalists should become familiar with the mistakes being discussed from COVID-19 and differences between COVID-19 and other pandemics to provide context on what to look for if another does occur. Some ways it could differ:

- The specific population(s) at risk may differ: It’s mostly older adults with COVID-19, but it was younger adults with 2009’s H1N1.

- Transmission could differ: Even if it’s respiratory, the incubation period and amount of asymptomatic and/or presymptomatic spread could differ, which would impact what types of public health measures are recommended to reduce the risk of spreading it — don’t assume they will be the same as with COVID-19.

- Point of origin and subsequent epidemiology could differ: Instead of the cities being hit hard in the beginning, it’s possible rural areas with farms will experience the biggest burden first.

- Antiviral treatment and vaccines will certainly differ.

The impact of a bird flu pandemic on national and global supply chains, the economy, education and schools, employment and other realms of life may also be very different, and journalists need to be prepared for those possibilities and questioning experts about them.

Current surveillance in humans

Tracking bird flu infections in humans in the U.S. falls under broader national flu surveillance, but the recent cuts to U.S. Health and Human Services — including veterinarians working on bird flu and food safety — raises questions about how comprehensive and functioning this system currently is.

The CDC issued a health alert on Jan. 16 advising that all positive influenza A tests be subtyped — identify the H and N types to see if it’s H5N1 or another strain — but it’s a recommendation, not a requirement. It also only applies to hospitalized patients, so subtyping may not be occurring with positive tests in clinics, and mild infections in people who don’t visit a clinic or hospital will be missed entirely.

Guidelines also exist for surveillance in close contacts of people infected with a confirmed novel influenza A strain. But people can refuse this testing. And testing may not occur at all in someone with mild symptoms, even if the virus causing those symptoms can cause more severe disease in someone else.

Key point: Surveillance is very sparse and decentralized for bird flu, and there are undoubtedly many missed cases. The burden falls on local hospitals, vets, clinics and public health and agriculture departments to identify these cases. Some worthwhile story angles involve finding out what kind of surveillance those local places are using and how they are preparing for possible cases.

Vaccine development for bird flu

Since the threat of a bird flu pandemic has been recognized for several decades, scientists have already made progress on possible vaccines. This process starts with creating a candidate vaccine virus (CVV), based on the appropriate influenza subtype, that can be used to make a vaccine against that virus. You can find past and present lists of existing CVVs at the WHO’s Global Influenza Programme page.

The U.S. currently has three licensed H5N1 vaccines, but these are specific to the strains, or clades and sub-clades (genetically similar groups of viruses), circulating in 2024-2025 and may not be as effective against a future clade. It won’t be possible to develop a functional vaccine for humans for a pandemic strain until the specific composition of that theoretical strain becomes capable of human-to-human transmission.

Fortunately, existing flu vaccines can be fairly readily manipulated to target new clades/strains. The best overview of the current status of bird flu vaccine development is this American Society for Microbiology article.

Key challenges with a bird flu vaccine, if a pandemic occurs, will share similarities with those of COVID-19 vaccines: production capacity, rapid distribution, access (and disparities in access), and vaccine hesitancy and uptake. But a new challenge, in the face of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s leadership of HHS and his history of anti-vaccine advocacy, will be whether the U.S. health agencies are willing to fund, approve or recommend a bird flu vaccine, as a recent HHS vaccine contract “review” has shown.

Resources

- Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) Virus Report for HPAI H5N1, prepared in June 2024 by the CDC Influenza Division.

- Risk to People in the United States from Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Viruses from the CDC, though this has not been updated since Feb. 28, and it’s unclear whether the current administration would acknowledge if the risk actually changed.

- Everything you need to know about bird flu by Amber Dance at Knowable Magazine.

- Avian Influenza (H5N1) Vaccines: What’s the Status?, American Society for Microbiology.

- Zoonotic influenza: candidate vaccine viruses and potency testing reagents, WHO.