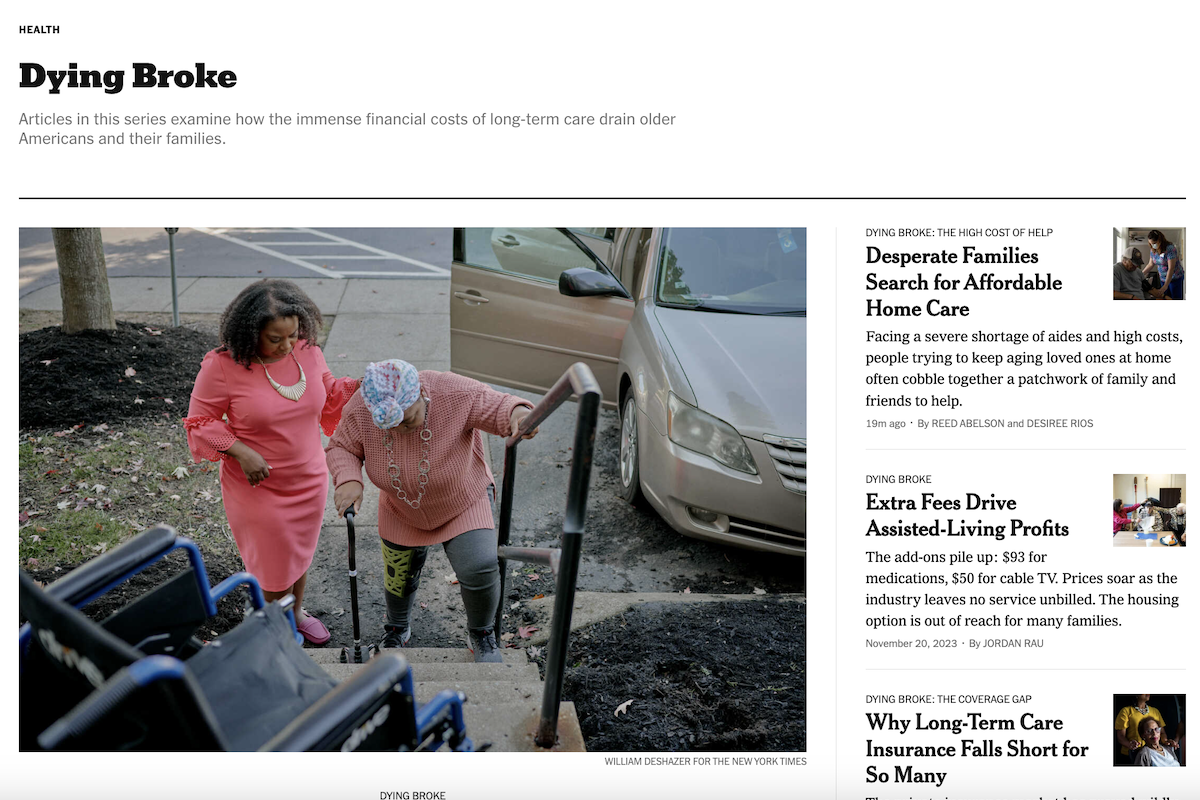

Nearly one in five Americans provide unpaid care to a family member. Many caregivers say it’s just something they must do, as they devote countless hours and financial and emotional resources to help a parent, relative or friend in the last part of their life.

Adult children often sacrifice their own retirement savings, while also getting squeezed as part of the sandwich generation, as they struggle to balance their own lives and manage the emotional and physical toll.

Some people have the means to afford assisted living or hire home care aides to help ease the burden and stress. But even those with long-term care insurance often discover too late that their policies are inadequate to meet their growing care needs.

New York Times reporter Reed Abelson and KFF Health News journalist Jordan Rau teamed up to take a deep dive into America’s long-term care system. They spoke with dozens of families and experts over the course of a year to find out why there aren’t better solutions to this obvious crisis of care.

Abelson and Rau answered questions from AHCJ about their series, “Dying Broke,” which documented these experiences from multiple perspectives and took a hard look at what the long-term care “industry” is doing — or failing to do — to meet the growing needs of eldercare in the United States.

(Answers were provided via email and written jointly by the two journalists.)

Your series chronicles the financial and emotional challenges of caring for vulnerable older adults. What prompted you to dive into this topic?

The number of older people who are going to need long-term care will explode over the next few decades as the boomers hit their 80s and 90s. The idea of this project was to look at this sprawling topic of long-term care for the elderly through a focused prism on the financial repercussions on the middle-class — both the older Americans needing care and their children. While we touched on a lot of things, such as quality of care and the Medicaid safety net, the spine of the project was always the financial challenges for people needing help doing activities of daily life or having dementia.

Did you have trouble finding people willing to open up and discuss their situations and challenges?

Getting people to talk frankly about finances proved to be harder than getting them to talk about the emotional and physical elements of taking care of their parents. There were many interviews where a person would bare very private details about their families and how their lives were affected but balk at going on the record about how they were paying for care. We were able to find people by networking through a variety of sources we both had cultivated from so many years covering the beat. We also used callouts posted on the Times website that solicited some strong stories. Because the project took a long time, we kept in touch with the people we were profiling and developed trusting relationships.

How long did it take to investigate and report out? What kind of roadblocks did you encounter?

It was well over a year, but not continuously; we worked on other stories along the way. The data was a challenge because we were focusing primarily on services people pay out of their pocket, like assisted living facilities or private home health aides. There’s little good information on that — particularly when it comes to finances for long-term care — in comparison to the extensive data you can get about Medicare. Our data journalist colleagues, Albert Sun at The New York Times and Holly K. Hacker at KFF Health News, did a fantastic job pulling out some strong material from the Health Retirement Study, a longitudinal survey of older Americans that collects information both about their health and finances.

The other major challenge was that peoples’ situations kept changing over the course of putting together the project. For instance, someone whom we were profiling as an example of being cared for at home, would move to a facility, and we’d have to readjust and rewrite. More than a few of our subjects died during the course of the project, which isn’t surprising since it is about the end of life, but it required a lot of revisions. It also demanded a sensitivity in talking with people because you never knew how their situations had changed since you had last interviewed them.

Was there an “aha!” moment when all of these interviews came together as a theme? There’s so much to unpack in these articles.

There was a point when the results of the data work came in and the findings echoed what our interviews and anecdotes were revealing. That made us confident that the people we profiled were representative of what millions were facing. But overall, we had a good idea pretty much from the start about what the story was and how to break it into its installments, looking at the burden on families, the cost of professional care — both in facilities and at home — and the inability of the private insurance market to address the problem and the lack of effective government intervention.

We’ve been trying to “fix” the long-term care system for a long time, but it remains fragmented, unreliable and precarious, often due to lack of available trained and paid workers. Do you see any good solutions on the horizon?

One of the most disconcerting things from our reporting was the lack of scalable solutions out there. There’s no organized effort to do more than just tinker around the edges of the existing “system.” Neither Republicans nor Democrats in Congress expressed any interest in fundamentally overhauling the system. The last major effort, the CLASS Act, a voluntary long-term care insurance program that was part of the Affordable Care Act, was repealed for being unworkable even before it launched. That said, Washington State has enacted a long-term care insurance program that’s mandatory for most workers, though its maximum payout of $36,500 isn’t going to cover costs for an extended period of time. Starting in January, California will stop looking at the value of most assets when determining Medicaid eligibility, which will allow more people to obtain long-term care services. But there is also a fundamental shortage of home health aides for those who want to stay at home, and so far, there aren’t significant steps being taken to address the need for more caregivers.

What advice do you have for local reporters who may want to follow up on long-term care issues in their communities?

This is one of those stories that’s easier to do on a state or local level than nationally. It’s not as hard to find people whose stories you can tell when you’re closer to the ground. Keeping the focus in one state allows you to be a lot more specific about Medicaid rules and what options people have among facilities and home care people. It was harder for us to generalize because each state’s Medicaid program is so different about how much money they allow people to earn to keep qualifying for Medicaid and what kind of protections exist for someone’s primary house, or what kind of programs exist to pay for care outside of a skilled nursing home. Cultivate Medicaid estate planning attorneys and elderly assistance groups to find people to profile, but also network. Everyone knows someone in this situation; that’s why the articles have resonated so widely.

Read more in the series:

- Desperate Families Search for Affordable Home Care

- Facing Financial Ruin as Costs Soar for Elder Care

- ‘I Wish I Had Known That No One Was Going to Help Me’

- What to Know About Home Care Services

- What to Know about Assisted Living

- Extra Fees Drive Assisted-Living Profits

- Why Long-Term Care Insurance Falls Short for So Many

- Long-Term Care Poll

- What Long-Term Care Looks Like Around the World

Jordan Rau is a senior correspondent for KFF Health News in Washington, D.C., and covers hospitals, nursing homes and the health care industry.

Reed Abelson has been a reporter for The New York Times since 1995. She covers the business of health care, focusing on health insurance and how financial incentives affect the delivery of medical care.