Noting that so many companies in the prescription drug supply chain are vertically integrated, the Federal Trade Commission voted unanimously on Tuesday to investigate the role pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) have on consumers’ costs and access to prescription drugs.

Given that health insurers own most of the largest PBMs and therefore own their affiliated mail-order and specialty pharmacy companies, the FTC ordered six PBMs to comply with requests for information on their operations: CVS Caremark (which owns Aetna), Express Scripts (a division of Cigna), OptumRx (a UnitedHealth Group unit), Humana (an insurer), Prime Therapeutics (which contracts with multiple Blue Cross Blue Shield plans) and MedImpact Healthcare Systems (which contracts with employers and government and commercial health insurers).

PBMs are middlemen that negotiate rebates and fees with drug manufacturers, create drug formularies and reimburse pharmacies for patients’ prescriptions.

For four years, Darrel Rowland (@darrelbrowland) has covered PBMs closely for The Columbus Dispatch in Ohio. The headline on his story about the FTC decision focused on the potential benefit of such a probe on consumers’ costs: “FTC agrees to ‘shine a light’ on how drug middlemen impact your prescription prices.”

Rowland quoted the newest commission member Alvaro Bedoya (confirmed May 11) who was candid in a written statement about PBMs’ role in the drug supply chain. “… nearly everyone is affected by PBM business practices,” Bedoya wrote. “For most Americans, pharmacy middlemen control what medicine you get, how you get it, when you get it, and how much you pay for it. Yet PBM practices are cloaked in secrecy, opacity, and almost impenetrable complexity.” Bedoya’s two-page statement is worth reading in full.

As Bedoya noted, the FTC inquiry is significant because PBMs operate one of the most complex organizations in health care, making them hard to understand — even for health care journalists — and their operations are challenging for readers to grasp as well.

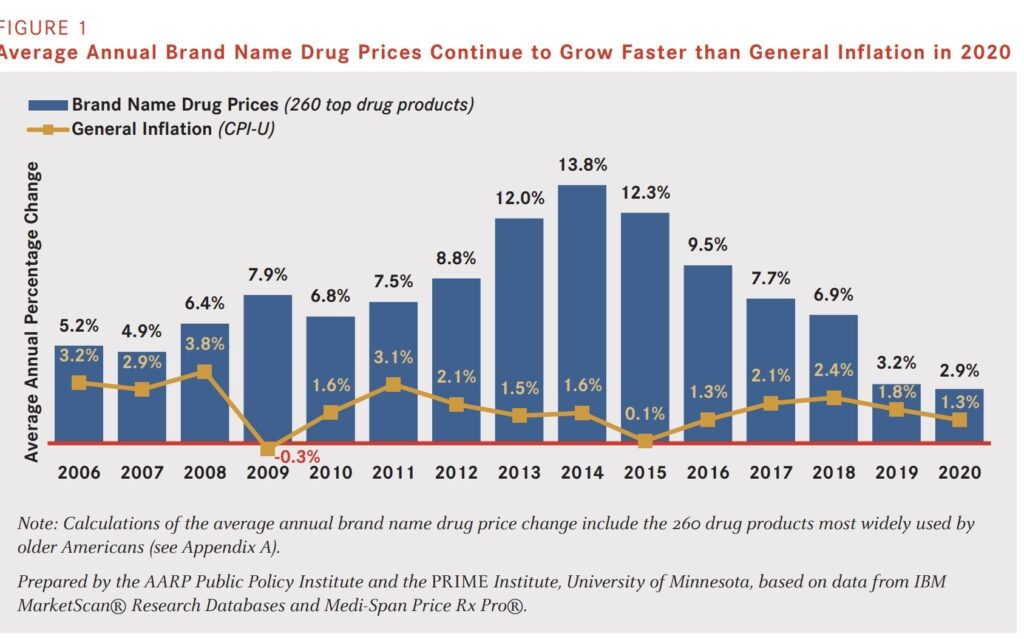

In recent years, PBMs have gotten larger and gained more control over what consumers pay for prescription drugs. In March, Bob J. Herman reported for STAT News that the five largest PBMs managed more than $422 billion in gross drug revenue last year, a 9% increase over the gross revenue they managed in 2020, and 56% more than the industry managed in 2015, he explained.

The five largest PBMs are CVS Health’s Caremark, Cigna’s Express Scripts, UnitedHealth Group’s OptumRx, Humana pharmacy, and Anthem’s IngenioRx, all of which are divisions of health insurers. Three of the PBMs — Caremark, Express Scripts and OptumRx — are so big they managed almost 90% of the nation’s gross drug revenue last year, Herman added.

Herman’s colleague, Ed Silverman, put the FTC probe into context, explaining that PBMs have a unique position in the drug-supply business because they help health insurers determine which medicines they should cover and the prices consumers should pay at the pharmacy.

The lack of transparency into how PBMs determine which drugs to cover and how much consumers and taxpayers pay for drugs has led to increased scrutiny into their business relationships with pharmaceutical companies and state Medicaid programs, Silverman wrote. “The complaints have mounted as a growing number of Americans say they are unable to afford their medicines,” he added.

The opaque nature of how PBMs work inflates drug prices and caused many independent pharmacies to close, reducing competition and allowing large chains to dominate local communities, he explained. “As an example, pharmacies point to CVS Health, which owns both the CVS Caremark PBM and the CVS chain of retail pharmacies,” he noted. In December 2017, the U.S. Department of Justice approved the merger of the health insurer, Aetna, and CVS Corp., which until that time had run a chain of pharmacies and a PBM.

In addition to setting prices, PBMs have an enormous influence on which drugs doctors can prescribe to patients and which pharmacies patients can use, the FTC noted.

In its inquiry, the agency said it will analyze the following practices:

- Fees and clawbacks are charged to unaffiliated pharmacies

- Methods to steer patients towards PBM-owned pharmacies

- Potentially unfair audits of independent pharmacies

- Complicated and opaque methods to determine pharmacy reimbursement

- The prevalence of prior authorization and other administrative restrictions

- The use of specialty drug lists and policies

- The effect of rebates and fees that PBMs get from drug makers on formulary design and the costs of prescription drugs to payers and patients

After requesting comments from the public on Feb. 24, the FTC received more than 24,100 responses.

For more details on how PBMs work, check out this comment letter from the Community Oncology Alliance to the FTC on May 25 and the accompanying footnotes: “COA Formal Comments to FTC on Harm of Pharmacy Benefit Manager Integration.” PBMs have 90 days to respond from the date they receive the order, the agency said.