It’s easy to understand the economic arguments against exposing people to medical treatments and tests that many experts say are unlikely to help them. But it’s been tougher to quantify medical reasons for avoiding what researchers call “low value” care.

A paper published July 23 in JAMA Health Forum may bring more clarity to the discussion.

About 1% of admissions for certain procedures widely considered to be of low value were linked to subsequent complications such as infections, foreign objects left in patients, falls and bedsores, wrote the authors of this paper, “Adverse events and hospital-acquired conditions associated with potential low-value care in Medicare beneficiaries.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate hospital-acquired harms for U.S. Medicare beneficiaries associated with low-value care,” the authors wrote.

Four of the authors are Kelsey Chalmers, Valérie Gopinath, Shannon Brownlee and Vikas Saini, all affiliated with the nonprofit Lown Institute in Brookline, Mass. The other co-author is Adam Elshaug, MPH, Ph.D., a professor of health policy at the University of Melbourne.

This paper should serve as a “wake-up call for hospitals to crack down on low-value services, for the sake of their patients,” wrote Judith Garber, also of the Lown Institute, in a blog post for the organization’s website. “All procedures, particularly invasive procedures in hospitals, carry some risk — and the risk of harm to patients is the same regardless of whether or not the procedure is necessary,” Garber wrote.

The study focuses on data from claims in Medicare’s traditional program from 2016 through 2018. The Lown Institute researchers looked for cases in which patients underwent treatments cited in previously published papers as having little benefit.

Among the studies guiding their choices was the widely cited “Measuring low-value care in Medicare,” which appeared in 2014 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

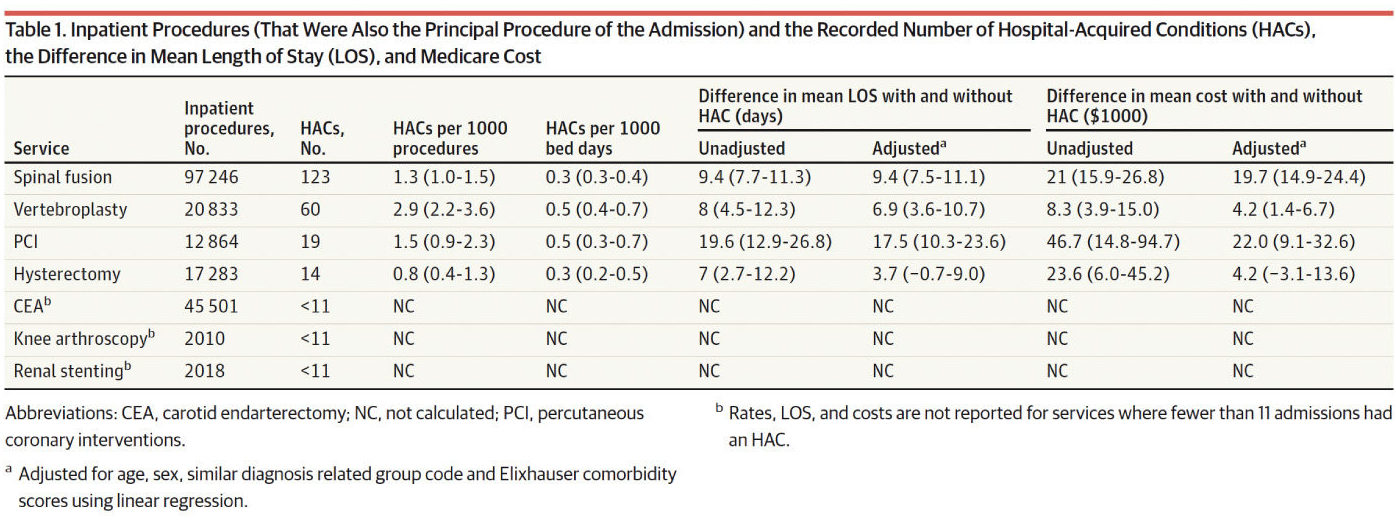

For their study, the Lown Institute researchers and Elshaug focused on seven procedures: knee arthroscopy, spinal fusion, vertebroplasty, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), carotid endarterectomy, renal stenting and hysterectomy for benign conditions.

Chalmers and her co-authors identified from the claims data 197,755 admissions where the low-value procedure was the main driver of the admission. Of these, 1,995 cases (1.0%) were linked to at least one of a set of complications, classified as either patient safety indicators (PSIs) or hospital-acquired conditions (HACs).

The complications included:

- bedsores (pressure ulcers) of different levels of severity

- collapsed lungs considered connected to medical care (iatrogenic pneumothorax)

- bleeding or swelling from tissues around an incision made during surgery (perioperative hemorrhage or hematoma)

- postoperative respiratory failure; blood clots in lungs (perioperative pulmonary embolism) or deep vein thrombosis

- catheter-associated urinary tract infection

- surgical site infections.

Study limitations included its narrow focus on the set of seven procedures and a select pool of potential harms, Chalmers and co-authors noted.

“The procedures included in this study represent a fraction of services that may be routinely overused and may lead to downstream harm,” they wrote. “There has been a groundswell of studies documenting new low-value care measures, but most are for unnecessary tests and imaging.”

The research was funded by Arnold Ventures, a philanthropy that is focused on efforts to redress low-value care.

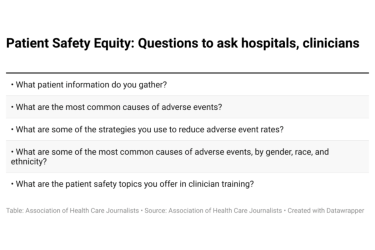

AHCJ asked the American Hospital Association (AHA) and several medical societies for comment on the paper. Lisa Satterfield, MS, MPH, senior director for health economics and practice management at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), disagreed with the Lown Institute researchers’ assumption that hysterectomies are “low value” if they are performed for benign indications.

Hysterectomies are regularly performed for benign indications, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, endometriosis and prolapse, Satterfield wrote in an email, adding that cases at higher risk for complications included those associated with more significant conditions.

Akin Demehin, director of policy at the AHA, urged caution in interpreting the study’s findings, due to its reliance on only one data source, Medicare claims. Demehin also questioned the use of patient safety indicators, saying they are often unreliable. Still, AHA concurred with the general aim behind the Lown Institute researchers’ proposal.

“We agree there are important opportunities to identify and reduce the volume of procedures whose benefit is not outweighed by costs or risks,” Demehin wrote to AHCJ.

This new JAMA Health Forum paper adds to a growing body of research about low-value care. Researchers are seeking to draw greater attention to the potential harms of treatments and tests judged to have little benefit for patients.

To try to generate more discussion about potential harms from low-value care, Deborah Korenstein of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and her colleagues created what they call a conceptual map. They published it in a 2018 article JAMA Internal Medicine titled “Development of a conceptual map of negative consequences for patients of overuse of medical tests and treatments.” It serves as a reminder that patients can suffer physical and psychological harm from low-value care, as well as financial losses.

This article was part of the “Less Is More” series that JAMA Internal Medicine, then called the Archives of Internal Medicine, kicked off in 2010. It highlights situations in which the overuse of medical care may result in harm and in which less care is likely to result in better health.

In addition, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign works with medical societies to help patients avoid tests and treatments considered unlikely to benefit them. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, for example, worked with Choosing Wisely on a set of recommendations. These include a caution against PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention) in stable, asymptomatic patients with normal or only mildly abnormal adequate cardiac stress test results.

What journalists can do

Journalists can help their audiences by explaining what studies have shown over the years about use of angioplasty for people with stable heart disease, cardiologist and researcher William E. Boden, M.D., told AHCJ in a telephone interview. Boden is a professor at Boston University School of Medicine and scientific director of the V.A. New England Healthcare System’s clinical trials network.

“We seem to have a really big problem, an evidence-practice gap if you want to call it that,” Boden said. “There’s a disconnect between what the evidence tells us and what physicians choose to do in terms of clinical practice.”

Boden is the lead author of a 2007 New England Journal of Medicine paper that reported the results of the COURAGE trial. That study found that although the addition of PCI to optimal medical therapy reduced the prevalence of the chest pain known as angina, this procedure did not reduce long-term rates of death, nonfatal myocardial infarction and hospitalization for acute coronary syndromes.

In a 2012 article in the Washington Post, “Why do cardiologists often pass up safe, low-tech treatments for chest pain?” journalist David Brown delved into why it proved difficult to convey to cardiologists the basic message of the COURAGE study, which was that they were “jumping to angioplasty and stenting too quickly in lots of patients.”

“It may lie in the culture of American medicine, which with little exaggeration can be summed up by the sentence: `Don’t just stand there, do something!’” Brown wrote. “When cardiologists see a big blockage in an artery during cardiac catheterization, most want to go after it.”

More evidence against use of PCI for stable angina arrived in 2017. A study known as the ORBITA trial marked a rare occasion when a randomized clinical trial was performed to see how much a surgical technique helped patients.

While this kind of placebo-controlled approach is common in studies of new medicines, it’s extremely rare in studies of surgical techniques. But for this study, 200 patients who had chest pain and blockage in arteries were randomly assigned to get either PCI or a procedure that mimicked it.

PCI did not increase exercise time more than the effect of a placebo procedure, reported Rasha Al-Lamee of Imperial College in London and her co-authors in an article in the Lancet, “Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomized controlled trial.”

For someone suffering a heart attack, PCI is the right treatment, as it can be in other cases, Boden told AHCJ. But it’s very difficult to help patients understand the “extremely nuanced” difference between cases where a procedure is appropriate and where it’s not, he said.

“You can certainly understand that our patients can get confused,” Boden said. “The lay public can’t really readily discern the difference between opening up a blocked artery in the setting of an acute heart attack versus unblocking a narrowed coronary artery in a patient with angina” or chest pain.

He called on journalists to try to make it easier for people to understand these distinctions. “Americans are smitten with high technology,” Boden said. “We assume that more is better. We assume high technology is better than taking medication (in the case of stable angina). So there’s a need for getting the truth out there.”

Here are some resources for reporting on efforts to address low-value care:

- Arnold Ventures: low value care webpage

- ABIM Foundation: Choosing Wisely

- Health Affairs: series on the ORBITA trial

- JAMA Internal Medicine “Less Is More” series: The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has been looking for several years at the issue of low-value care. In a March 2021 report to Congress about the state of the giant health care program, MedPAC estimated that in 2018, between 22% and 36% of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare received at least one low-value service. Estimated Medicare spending for these services ranges from $2.4 billion to $6.9 billion, MedPAC said.

Friday: Experts seek to reframe debate on medical care judged to have little benefit for patients.