We don’t yet know the severity of COVID-19’s long-term effects on the brain, but a group of international researchers is aiming to find out.

The Alzheimer’s Association and scientists in 30 countries are forming an international consortium to track and assess COVID-19 patients. According to a paper announcing the study, scientists will look for any lasting effects on the central nervous system which may lead to late-life cognitive decline, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and other brain disorders. The World Health Organization is providing technical help.

Teams will collectively assess some 22 million COVID patients and other people already participating in other brain health studies, looking for markers of their underlying biology. The Washington Post’s Tara Bahrampour wrote this excellent story detailing the initiative and what researchers hope to learn.

There are some striking similarities between COVID-19’s biology and Alzheimer’s, according to the paper’s co-author, Heather Snyder, Ph.D., vice president, medical & scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association. “We know that COVID-19 triggers a massive immune response, an inflammatory response; some individuals with COVID_19 have a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Those are also key pathways that we see in Alzheimer’s,” she said in a phone interview.

Many questions about COVID and the brain have yet to be answered, Snyder said. Among them: why there is commonly a loss of sense of taste and smell, which can be linked to brain function, and similar reports of “brain fog” for weeks or even months after patients recover from the illness. Some people are likely to face long-term consequences, according to this NPR story.

Long-term neurological effects of COVID-19 also have potentially serious policy implications, according to Walt Dawson, D.Phil., an assistant professor at Oregon Health Science University with the Layton Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease Center. He notes that about a quarter of COVID-related deaths among older adults had been those with Alzheimer’s or other dementias. This is primarily due to the prevalence of people with the disease in long-term care settings.

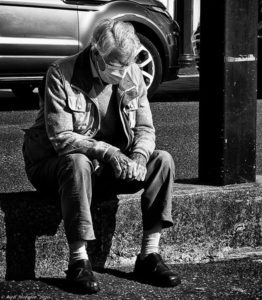

Additionally, the very measures taken to protect people and reduce the spread of infection also have resulted in increased social isolation and loneliness, particularly among older adults who may be at high risk for dementia. “The impact of that isolation and the disruption of our social networks and of our daily routines in itself is a huge risk factor for increased rates of dementia,” Dawson said in a phone interview.

Last July before the election, President-elect Joe Biden’s team proposed more funding for family caregiving across the lifespan, targeting $775 billion for improving home and community supports for children, the elderly and individuals with disabilities. He also proposed a new tax credit for family members caring for aging relatives.

“There is an opportunity to think broader than just the caregiving pieces, there is a real opportunity to think about how do we create a better long-term care financing system,” said Dawson. “There’s a role for a much more coordinated national strategy to fund and support access to quality long-term services supports that don’t impoverish or bankrupt people. This is a this is an opportunity to really tackle that.”

The global study will look at the long-term consequence of the virus in people of different ages, those in different care situations and people from different genetic backgrounds, Snyder said. In the United States, African Americans are two times more likely to develop cognitive changes seen in Alzheimer’s and Hispanic and Latino individuals are one-and-a-half times more likely. Initial data from the study likely will be published in early 2022.

Meanwhile, the U.S. needs a plan to care for what could be a coming wave of older people with increased cognitive impairment, according to Dawson. “We need a national strategy and a comprehensive approach to providing better long-term services and supports that don’t rely on state budgets that are cyclical. When there’s a substantial shock and crisis like that, they’re absolutely put under pressure and folks will unfortunately suffer.”

Journalists may want to explore how COVID-related cognitive impairment is impacting the older population in general and how it is disproportionally affecting different racial and ethnic groups and the families who help care for them. What services and supports are available at the state or community level? What does insurance pay for — or not? Have families had discussions about aging in place or end-of-life wishes due to lingering effects of COVID? Are health care providers seeing an uptick in cognitive issues among their patients?

The Alzheimer’s Association suggests that journalists also talk with local individuals who are experiencing brain fog and build up anecdotes on the record until there is data. Talk to the local clinician until there is data. Tell the anecdotal story so that it’s on the record.