Covering mental health issues among older adults first means understanding the differences between issues of social isolation, loneliness, depression, and the effect of cognitive decline. Each issue may affect a person or several may be occurring simultaneously. Don’t interchange the terms however, because they’re not the same condition.

At last week’s Journalism Workshop on Aging and Health in Los Angeles, panelists stressed the importance of getting it right. You can be alone, but not lonely, or socially isolated. You can be socially isolated but not lonely. You can be either, or both.

Loneliness is subjective, according to Carla Perissinotto, M.D., associate chief for geriatric clinical programs, University of California, San Francisco. Loneliness relates to discrepancies between actual and desired relationships and causes a sense of discomfort. Social isolation is something more quantifiable in terms of the number of relationships.

“It’s not about quality but how much are you engaging with other people,” she said.

And either can exacerbate depression. That presents a real challenge for physicians; many of whom don’t really have the skill set to identify these conditions in patients, according to Perissinotto.

Loneliness doesn’t automatically equate to depression either. The literature shows the majority of people who are lonely are not depressed, she said. There can be overlap but it’s not the same.

Depression is a state and feeling of diminished self-worth. “We often use term depression when the person may or may not express sadness, something perhaps negative, or demoralizing,” said Lon Schneider, M.D., professor of psychiatry and the behavioral sciences, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine.

It’s important for health providers to know the individual’s mood state, especially if they have dementia. “They may not be depressed; they may be apathetic,” he said. Stop to consider the differences between apathy, depression, and loneliness.

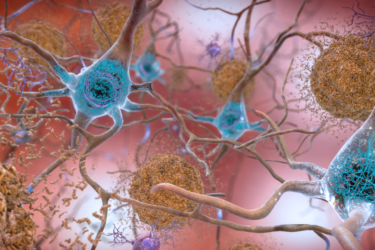

When writing mental health stories, journalists should also make sure they understand the difference between Alzheimer’s disease, other dementias and cognitive impairment, said Patrick Arbore, Ed.D., director and founder, Center for Elderly Suicide Prevention & Grief Related Services, Institute on Aging.

Dementia is a syndrome which impairs mostly memory to such a degree that there is impact on activities of daily living. Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia, and most people start showing symptoms in after their mid-60s, according to the National Institute on Aging. This AHCJ tip sheet can help reporters understand the various forms of dementia and their impact.

“People who have dementia syndrome versus mild cognitive impairment may actually have substantial cognitive impairment, but there’s less interference in ADLs, so you can get around,” Abore said.

All of these conditions are connected to another issue that’s equally concerning and little discussed: suicide among older adults. Between 1999 and 2017, suicide rates increased by 30% for entire population according to Abore, who also founded Friendship Line as a means to address this public health problem, and recruit volunteers of all ages who specifically chosen to counsel older people.

He said older adults weren’t calling crisis lines, because they didn’t see themselves as being in crisis. Instead, they were suffering from chronic loneliness and undiagnosed depression. Many older people just want a conversation.

“They’re isolated, lonely and often depressed.” Abore said. Notably, half of the calls to the Friendship Line are from seniors in California.

“If we could reduce loneliness and social isolation, we’d have a fighting chance on depression and suicidality.” Reducing the stigma surrounding mental health treatment among minority populations is also a huge challenge, he said. There’s a need to recruit more minority mental health professionals. “If staff doesn’t look like you, if participants in a support group don’t look like you, it’s a barrier.”

He advised journalists to be cautious when looking at suicide rates for seniors. Since the older population is increasing, it can appear that rates are decreasing. Parse the data carefully. For example, white men 85 and older have a rate of suicide that’s four times national average. But getting down into the weeds on these figures is a challenge, due to what Abore called a “lack of interest in the oldest old.”

It’s also important to look at the root causes of isolation, loneliness, and depression, according to Perissinotto. We can connect people to services but without addressing the causes, it doesn’t matter what your intervention is. Figure out where the roadblocks are, whether that’s income, safety, physical health issues, medication effects, or other causes.

While mental health issues affect older adults across populations, they can be worse in historically underrepresented communities, due to lack of resources, lack of representation, inability of social and healthcare systems to be responsive and involved, said Schneider.

However, research in minority communities is sparse. There may be significant barriers to care and treatment, such as access and affordability, as well as social or cultural stigma. There are also concerns about isolation and loneliness among immigrant populations and among older LGBTQ adults. However, a lack of large studies makes it difficult to confirm data gathered to date.

Reporting on these issues can help shed additional light on the need for community-based, culturally appropriate services, point out barriers to care, and help destigmatize mental health issues among all older populations, panelists said. It can be an uncomfortable topic to report on but making it part of the aging conversation may even help save lives.

Related

Health Affairs: Social Isolation, Loneliness, And Violence Exposure In Urban Adults