It’s hard to fathom how someone could abuse a vulnerable older person, especially a family member. Unfortunately, elder abuse is growing – by some estimates, one in 10 Americans 60 or older have experienced some form of elder abuse.

It’s hard to fathom how someone could abuse a vulnerable older person, especially a family member. Unfortunately, elder abuse is growing – by some estimates, one in 10 Americans 60 or older have experienced some form of elder abuse.

Funding needs to increase at the federal, state, and local levels to address the causes, consequences and solutions to this issue. As a society, we need to come to terms with this challenge and do a better job of taking care of our elderly population, according to panelists at AHCJ’s October workshop on aging and health in Los Angeles.

Despite an obvious need, funding is not keeping pace with rising caseloads, according to Laura Mosqueda, M.D., dean of the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California. An adult who is abused in one way is often abused in other ways, a concept known as polyvictimization, she said. This may include emotional/psychological abuse, financial abuse, scams, and neglect.

When it comes to elder abuse, there is, unfortunately, a lot of material to cover. This post focuses only on one piece of the problem, physical abuse. Follow-up posts will look at other forms of abuse.

Physicians face numerous challenges when reporting physical abuse, which can range from pulling a person’s hair to hitting, punching, slapping, throwing food or water on a person … or worse. “These are all things I’ve personally seen,” Mosqueda said. It’s pretty rare that someone gets arrested for it, however. It’s difficult getting victims to actually admit and identify the problem to health providers or law enforcement and following through.

Mosqueda spent much of her time highlighting the issue of neglect, the most common type of abuse. Neglect is a failure to provide the basic necessities of life — food, clothing, shelter, and medical care.

Some estimates range as high as 5 million elders who are abused each year, although according to the NCOA, only 1 in 14 cases of abuse are reported to authorities. NCOA also includes willful deprivation as part of these statistics, which encompass “denying an older adult medication, medical care, shelter, food, a therapeutic device, or other physical assistance, and exposing that person to the risk of physical, mental, or emotional harm — except when the older, competent adult has expressed a desire to go without such care.”

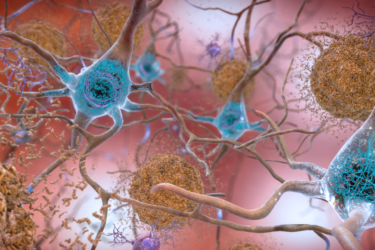

Mosqueda thinks those figures are even higher. “One in six is our best estimate, and for those with dementia, it could be as high as one in two.” The reality is, the majority of elder abuse is committed by family members, and may begin unintentionally.

She acknowledged that being a family caregiver is “incredibly difficult,” especially if the loved one has cognitive impairment. “But that in no way makes an excuse or makes it acceptable to abuse or neglect somebody.” Sometimes neglect can be connected to long-time family dynamics, and it’s incumbent upon physicians to try and find the root cause. She has developed an abuse intervention model that can “help dismantle a very complicated problem.”

Not only is it difficult for an older person to defend themselves physically, they also may be in denial that a child, or grandchild has actually inflicted physical or emotional harm on them. Emotional abuse may include playing on their fear of losing what remaining independence exists, Mosqueda said. “For example, if you don’t do X, I will put you in a nursing home.”

Abuse impacts more than just the person involved, she said. “What does that say about us as a society that we’re allowing this to happen?” One of the most disturbing things she’s heard is for when someone says abuse doesn’t matter so much if the person has Alzheimer’s because they’ll forget about it anyway. “To me, that’s just a heartbreaking comment to hear and makes you wonder where our humanity is.”

It can be difficult for physicians to diagnose physical abuse, because there often aren’t red flags, they’re more like pink flags. It requires a look at interaction between caregiver and older adult, interview techniques, and laboratory evidence. Perhaps someone has an injury with big or impossible explanations, or a pressure sore that’s allowed to fester until it’s stage four and down to the bone. There may be bruising patterns inconsistent with a fall, or malnutrition, or hygiene issues. Often a caregiver will try to justify a problem with a claim such as “of course they have a pressure sore, they’re old. Of course they have a fracture, they’re old.”

Ensuing wellbeing among older adults includes understanding the role of ageism in our culture, and providing resources that empower older adults and families. That may include respite care, mental health or social service support. Journalists can do their part by reporting on these issues and ensuring that seniors and family members are aware of available community help.

During the Q&A session, Mosqueda challenged reporters to take different tacks with abuse stories, because “a lot of times reporters say they can’t do a story unless they have a victim.” She doesn’t think it’s fair for someone who experienced any type of abuse to be “victimized” again by sharing their story.

Of course, that depends on the editor or media outlet. But Mosqueda’s point about finding more creative or offbeat angles to report on this topic is certainly worth considering.

- This How I did It from Tracy Breton explains how the she worked with student reporters to tackle the issue for a special series in the Providence Journal.

- This article by Charles Pillar looks at how one hospice death turned into an investigative series.

- The CDC has a list of data and other resources to assist in your reporting.

- The Administration for Community Living recently launched the national adult maltreatment reporting system (NAMRS); it’s designed to improve prevention and intervention.

- Reporters in California should also visit UC Irvine’s Center of Excellence on Elder Abuse and Neglect website, which offers multiple resources for professionals; you may find some story ideas or sources here.

- While there wasn’t time during the presentation to take a deeper dive into the issue of abuse in nursing homes or assisted living facilities, it’s also an important segment to investigate. This GAO report, released in August, compared federal requirements for reporting and investigating elder abuse in nursing homes and assisted living facilities.