Much of the post-Thanksgiving media coverage has focused on Omicron, the SARS-CoV-2 virus variant detected circulating in South Africa and labeled a variant of concern (VOC) by the World Health Organization on Nov. 26. The other variants of concern are Delta, Alpha, Beta and Gamma.

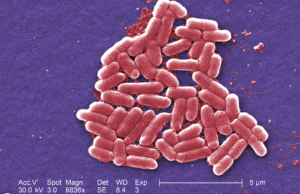

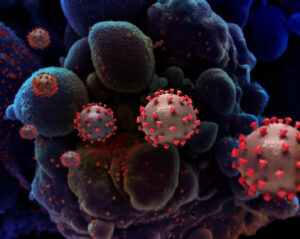

WHO added Omicron to the VOC list based on available evidence, including the fact that the variant contains more than 30 mutations in the spike protein, the primary antigen that all WHO’s approved COVID-19 vaccines rely on to evoke an immune response. These mutations are all distinct from the genome of the ancestral (original) virus discovered in Wuhan in late 2019, and many of them already exist in the Delta and Alpha variants.

Some of these mutations have the potential to make the virus more transmissible (like Delta does), cause more severe disease or reduce the effectiveness of vaccines that prevent COVID-19 disease (like Beta does). However, there isn’t enough clinical evidence (real-world evidence from actual infections) to say yet whether the Omicron strain is more transmissible, more pathogenic, or less susceptible to protection from the vaccine.

Journalists should therefore keep in mind that the science of the variant is still evolving and report stories with the caveat that there remain a lot of unknowns, a normal aspect of the scientific process. The public is going to have to wait for more definitive information. Anthony Fauci, M.D., chief medical advisor to President Biden and head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases told Biden on Nov. 28 that he expects it will be another two weeks until scientists have more definitive answers. That feels like an eternity in COVID-time, and it’s okay to acknowledge that, but it’s also warp speed in real-science time, which is also important to keep in mind and convey to readers.

In the meantime, nothing changes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s advice for protecting oneself and others from COVID-19: get vaccinated, get boosted, wear a mask indoors in places with people outside your household, avoid large indoor crowds and get tested if you have symptoms.

“We still have no scientific updates on Omicron’s impact on immunity escape or transmissibility,” wrote Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist with the University of Texas Health Science Center in a blog post. “If you’re hearing anything right now…it’s purely speculation. Hypotheses are important to discuss, but not the solid evidence we need. Getting answers takes time because good science takes time. I give it a week or two until the evidence starts rolling in.”

What is Omicron and why does it have this name?

A variant designated B.1.1.529 [now called Omicron] was first discovered in Botswana on Nov. 11 and then was detected in Hong Kong and South Africa several days later. On Nov. 26, South Africa health officials alerted the WHO that the strain had 32 mutations and was spreading quickly. The WHO then determined it was a variant of concern [other determinations include variants of interest and variants under monitoring] and named it ‘Omicron’ based on the Greek alphabet. [This naming convention has been used with previous variants including alpha and delta, but both Nu and Xi were skipped because the former was confusing verbally (“Nu variant” could be mistaken for “new variant”) and the latter is a common surname.]

Is it circulating in the U.S.?

Though Omicron hasn’t been detected in the U.S., Fauci said on Nov. 27 that he “wouldn’t be surprised” if it were already spreading in the U.S. The CDC updates data on variants in the U.S. on Tuesdays. One thing to note is that Omicron was first identified in South Africa, but that doesn’t mean it arose in South Africa. South Africa has an extremely robust viral surveillance infrastructure and extensive resources for monitoring new variants that don’t exist in most countries in the world, so it’s not surprising that two variants of concern were identified there.

Why are scientists so worried about Omicron?

The initial reports about Omicron identified 32 mutations on the virus’s spike protein, the part of the virus that the immune system uses to identify it as an intruder and begin making antibodies against it. However, it’s important to keep in mind that the total number is less important than how those various mutations might affect the virus’s ability to survive, replicate, spread, and potentially evade the immunity conferred by either vaccination or prior infection.

The spike protein includes the receptor binding domain (RBD), where the virus attaches to cells and infects them. Several of the mutations are ones seen in Delta that are associated with increased transmissibility. There were more than 15 to 17 mutations observed on the delta variant, which is more than twice as transmissible as the original Alpha variant, which was more transmissible than the original coronavirus first detected in Wuhan. “If we were looking out for mutations that do affect transmissibility, it’s got all of them,” University of Oxford evolutionary biologist Aris Katzourakis told Science.

The detection of Omicron has coincided with a rise in cases in South Africa. In one region of South Africa, the test positivity rate jumped 300%. What isn’t known, however, is how severe infections are, how many of those infections are Omicron versus a different variant, and how many of those who tested positive were vaccinated. Just 21.6% of the South African population has received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine. The variant has been identified in about a dozen other countries as of Nov. 28. Again, there is no further information about how severe cases are or how many of those cases were among vaccinated or unvaccinated people.

South African scientists and vaccine manufacturers are currently studying how well vaccines prevent infection from the Omicron variant. Fauci said that manufacturers are preparing to make changes to their vaccines if necessary.

How worried should Americans be?

Additional worry is not necessarily helpful, and not enough information is available at this time to speculate on what Omicron means for people in the U.S. Vaccination is likely to provide protection, but it will take another few weeks to begin to have a fuller picture of how well the currently available vaccines can protect against infections with Omicron. “I’m afraid patience is crucial,” Jeremy Farrar, head of British nonprofit Wellcome Trust, told Science.

Human immune systems do have the ability to adapt to SARS-CoV-2 mutations, so those who have been vaccinated, or have previously been ill with COVID-19 are likely to have some protection from the new virus. One way vaccines work is by causing the immune system to produce antibodies that are specific to a single pathogen, including whatever that pathogen’s current genome is. Often, however, antibodies can provide cross-protection against a pathogen that looks similar to the one they were designed to fight, which is why current vaccines can still offer protection against the variants detected since the vaccines were developed.

But vaccines also work by stimulating two types of immune system cells: T cells and B cells. T cells have two basic functions — killing the pathogen and teaching B cells what the pathogen looks like. B cells are the antibody factories. Vaccines can induce “memory” in both T cells and B cells so memory T cells and memory B cells can remember what to do when they see a pathogen again, even if antibody levels are low. (This is why even low antibody levels from waning over time don’t necessarily mean you’re not protected.)

B cells are adaptable and can adjust their antibodies based on what an arriving pathogen looks like. What all that means: when a body with anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies of any kind encounters Omicron, the T cells and B cells will be able to start mounting a defense against it more quickly than they would if the body had no anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies of any kind. So yes, it is extremely likely that vaccination will offer some protection, at the very least against more severe infections from Omicron, though it’s not possible to say how much yet.

On Nov. 28, Fauci told Biden that it will take approximately two more weeks to have more definitive information on the transmissibility, severity, and other characteristics of the variant and that he continues to believe that existing vaccines are likely to provide a degree of protection against severe cases of COVID, according to the White House press office.

What is the U.S. doing about it?

The U.S. imposed a travel ban from South Africa and other countries on Nov. 27 for non-U.S. citizens. Not all the countries included in the travel ban have detected cases of Omicron. The travel ban is controversial, with strong negative backlash from many infectious disease experts, because it is likely that Omicron is already circulating in the U.S., and the ban may be viewed as punishing South Africans for reporting the variant to global health authorities. Proponents of the ban say it could help slow its circulation in the U.S., but it’s not clear what data supports that claim.

The CDC also said that it is monitoring COVID-19 to determine if and when the variant is spreading in the U.S. However, the U.S.’s genomic surveillance is not as advanced as that of several other countries, particularly the UK and South Africa; U.S. surveillance could easily miss low levels of Omicron if it is already here. So far, the U.S. has not imposed any travel bans on the other countries where Omicron has been detected in arriving travelers.

What does Omicron mean for international travelers?

Until researchers have more data on Omicron, it’s not possible to offer specific recommendations regarding travel. People may choose to suspend or delay non-essential travel to countries where the variant has been detected, but the variant is likely already circulating in countries that have not yet reported detecting any cases. Anyone who travels internationally should follow the CDC’s recommendations for international travel, including being fully vaccinated before traveling and wearing a mask on public transportation, in airports and during flights.

Resources for journalists

- Take a look at this AHCJ tip sheet with names of vetted experts to call. It is also a guide to covering SARS-CoV-2 variants.

- Here is a list of variant experts to follow on Twitter: htps://twitter.com/i/lists/1341114313768091652 (some of these folks may be reached via Twitter for comment) Other experts not on Twitter include Cecile Viboud, Martha Nelson, Mark Denison, Adam Rambaut, Oli Pybus, Katrina Lythgoe, and Katia Koelle.

- The New York Times variant tracker appears to be updating most quickly where Omicron is being detected. The map denotes detection from an incoming traveler versus local transmission.

- The CDC keeps an updated list of the countries whose residents are restricted from traveling to the U.S. presently.

- Our World in Data has an explorer that allows you to track infections by variant.

- For those interested in the nitty-gritty details of the mutations and the science of the variant, two very helpful Twitter threads include this one by Jeffrey Barrett, director of the COVID-19 Genomics Initiative at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the UK, and this one by Trevor Bedford, Ph.D., an associate professor at Fred Hutch.