One of the most thorough analyses of the quality of hospital and health plan price transparency data got little attention when it was published last fall. Nonetheless, the 185-page report from the Purchaser Business Group on Health (PBGH) in Oakland, Calif., is useful for health journalists nationwide because it shows the problems employers face when contracting with health insurers and hospitals for workers’ health coverage.

What may be the most concerning finding is that the report identified fees that are hidden from employers, PBGH said in a press statement. Not only do hidden fees impede price transparency, they also raise questions about what other data hospitals and health plans have concealed since the price transparency rules went into effect in 2021 for hospitals and 2022 for health plans.

Another important finding is that many of the hospitals do not have the quality to match their reputations, PBGH President and CEO Elizabeth Mitchell told me in an interview. “A potentially striking lesson is that all of the so-called ‘value networks’ that the health plans sell really are not,” she added. “If you’re a health insurance company, theoretically, that is your day job. Yet insurance companies are not effective at managing costs in a way that translates for self-insured employers and their workforce.”

Evaluating hospital price, quality and safety together

Published Oct. 14, the report combines price, quality and safety metrics that address the need self-insured employers have for comprehensive data when contracting with hospitals and insurers, as Peter Wehrwein explained in Managed Healthcare Executive.

The report also shows how you can report on rising health care costs as an economic and health issue: When employers pay more every year to health insurers, hospitals and other providers, those increases force companies to reduce wages and layoff workers, as we reported here. A 1% rise in health prices leads to more deaths of about one per 100,000 (2.7%) because about one in every 140 individuals who become unemployed die from suicide or drug overdose, the research showed.

The PBGH report allows employers and journalists to compare what they paid against what they should have paid in 10 large health care markets: Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, New York City and Northern New Jersey, Northern California, Phoenix, Oregon, Seattle and Puget Sound, and Southern California. For the report, PBGH collected data from three of its large employer members: Boeing (182,000 workers), Qualcomm (52,000 workers), and the City and County of Denver (11,000 workers). Those three employers are among the 40 members of PBGH who together spend $350 billion on health care annually for their 21 million employees.

In other words, the findings show that employers could — and should — negotiate better deals with hospitals, Mitchell commented. Better deals have the potential to lower health care costs for employers and their workers.

Hidden hospital fees

“For decades, the health care industry has fought to keep pricing hidden because opacity enabled them to overcharge employers and employees,” Mitchell said in a press statement. “This project finally puts the truth in employers’ hands. It shows them not just what they paid, but what they should have paid — and that discrepancy is where hidden fees and profiteering live.”

Hidden fees raises questions about what other data hospitals and health plans have concealed since the price transparency rules went into effect. Under those rules, hospitals and insurers must provide clear, accessible prices online in machine-readable files (MRF) and on a list of shoppable services (meaning non-urgent) in a consumer-friendly form.

The data will help employers negotiate more favorable health insurance contracts this year and in the coming years and give them the information needed to expose hidden costs and demand lower prices.

With that data they can hold hospitals, insurers and other vendors accountable for their charges, PBGH said. Also, the report could transform how businesses contract with insurers and hospitals, since it shows which hospitals and health systems deliver safe, high-quality care.

A transformative analysis

Almost half of all Americans (48.6%) get their health insurance coverage from employers, according to KFF, and most of those employers are self-insured, also called self-funded. Self-insured employers do not buy insurance directly from health plans. Instead, they contract with insurers to limit the rising cost of care and manage their networks of hospitals and health systems. Self-insured employers set aside funds to cover all employee’s health costs except for unexpectedly high costs for which they buy reinsurance.

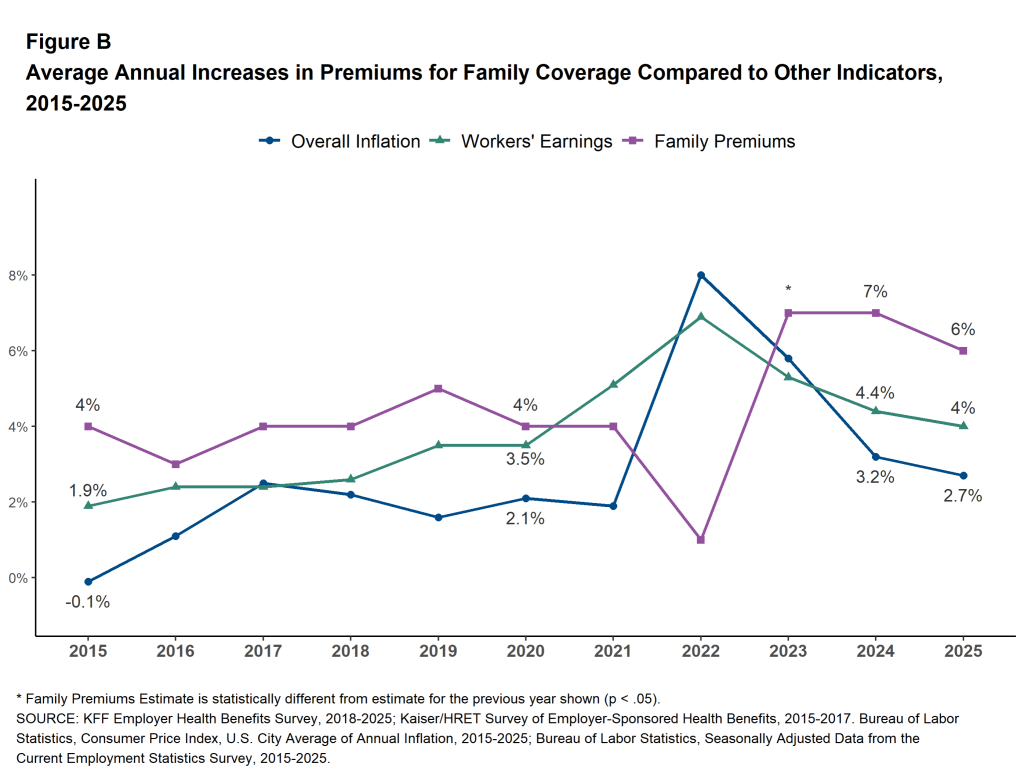

KFF’s annual report, the 2025 Employer Health Benefits Survey, shows health insurance costs rise almost every year faster than other costs. Last year, health insurance costs rose 6%, wages 4% and general inflation 2.7%, the report showed. Rising health costs cut into what employers pay in wages and thus limit what consumers can spend on groceries, utilities, rent and childcare.

But, for health insurers, rising health costs allow them to report higher income and profit to investors. “They [health insurers] are completely disincented from reducing health care costs,” Mitchell explained. “They have the opposite incentives of self-insured employers and families.”

Resistance from insurers

Gathering the data took more than a year, due in part to resistance from insurers and hospitals, Mitchell commented.

“There are a lot of results we couldn’t share because of agreements with the employers and, in many cases, the health insurance companies put serious restrictions on what we could do with the data,” she said. “That is antithetical to transparency.”

The next step will be a deeper dive into the results to understand how insurers and hospitals use employers’ funds.

“The report is the tip of the iceberg for the utility of the data,” Mitchell said. “We are embarking now on analyses for our members to understand why they differ as much as they do.”

Here’s an example: “If the cost of a service as reported by a hospital is, let’s say, $100, and, yet, the negotiated rate that the insurer paid was $200, where did that other $100 go?” she asked. “That means there’s room to cut costs.”

Employers’ fiduciary role

For employers, the report can help them meet their fiduciary role to cut health costs for themselves and their workers, Mitchell added. Under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, employers have a responsibility to run their health plans solely in the interest of participants and beneficiaries. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 added to employers’ fiduciary requirements.

That fiduciary role is significant because U.S. employers provide health insurance to as many as 164.7 million people under age 65, according to KFF. That’s more than Medicare (69 million or 14.8%) and Medicaid (76.7 million or 20.4% of low-income Americans, including 7.2 million children in the Children’s Health Insurance Program).

The fiduciary role might seem arcane, but it’s important for another reason, Mitchell noted. “High health care costs get built into the price of goods, like cars, groceries and most other products,” she said. “Just last year, the teachers in my neighborhood went on strike for a wage increase, and they got it. And all of it went to increased [health insurance] premiums. So they didn’t even see any actual increase in their pay. That happens all the time.”

Resources

- A conversation with Elizabeth Mitchell, president and CEO of PBGH, Peter Wehrwein, Managed Healthcare Executive, February 2026

- Trump Urged to Go Further on Health Price Transparency Rules, Lauren Clason, Dec. 4, 2025, Bloomberg Law

- PBGH aiming for accurate pricing for employers with data project, Jeff Lagasse, Healthcare Finance, Oct. 19, 2025

- PBGH launches data project arming employers with accurate pricing information, Paige Minemyer, Fierce Healthcare, Oct. 14, 2025