Editor’s note: This article was updated on Feb. 3, 2026, to include more recent and relevant information for the 2026 measles outbreak.

It’s been just over a year since a measles outbreak began in west Texas that eventually exceeded 800 cases and contributed to some of the 48 additional outbreaks in 44 states in 2025, resulting in more than 2,000 cases and three deaths last year.

This year is off to an even worse start with 588 measles cases reported to the CDC as of Jan. 30, most of them in a major outbreak in South Carolina. While the CDC’s update as of Jan. 30 only lists 467 cases there, the state’s dashboard has already updated that number to 847 cases.

An additional 16 other states have also reported cases, particularly North Carolina, Utah, Arizona, and Florida. (You should treat the CDC numbers as substantial underestimates because of delays in reporting and consult individual state department of health websites for the most up-to-date information. For example, the CDC lists 10 cases in Arizona, but their state website shows 24 cases.)

These numbers are already higher than what Texas saw at the start of last year — and last year saw the highest total cases of this disease since 1992. Measles was eliminated from the U.S. in 2000, which means it did not continuously circulate in the country and all cases that occurred were imported or arose from an imported case. However, public health experts are now bracing for the U.S. to lose its measles elimination status, as Canada did at the end of last year.

Adding to these concerns are new reports of measles cases at a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facility in south Texas. Measles is the most contagious disease known to humans and is particularly difficult to control in places where people live in close quarters.

You’ve probably already spent a significant chunk of time reporting on measles last year, but you should be prepared to continue reporting on this disease and on the declining measles vaccination rates that are helping fuel these outbreaks.

You will also likely have to continue countering inaccurate or misleading information propagated by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert Kennedy, Jr., a longtime anti-vaccine advocate who already exacerbated a deadly measles outbreak in American Samoa in 2019. Hawaii Gov. John Green even alleged Kennedy was responsible for causing additional deaths during that outbreak.

We’ve updated our measles post from last year to include additional information about the new outbreaks, tips for reporting on vaccine hesitancy, and more reliable resources than the CDC about measles, the vaccine, and other infectious diseases. Despite the ongoing coverage of measles last year, many communities have not (yet) seen an outbreak, and you should be prepared to educate and inform your audiences in those areas if a case does occur.

Facts about the measles vaccine

The only way to prevent measles is with the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, which is 93% effective with one dose and 97% effective with two doses against measles. The vaccine was tested in placebo-controlled trials and is very safe. The most common side effects are soreness at the injection site, temporary pain or stiffness in the joints and a mild fever.

About four in every 10,000 children who get the vaccine between 12-15 months old will experience a febrile seizure — a seizure caused by a fever — in the 7-10 days after getting the vaccine, but these seizures do not have any long-term effects. The risk of a febrile seizure is actually higher (9.5 per 10,000) for children who get the vaccine between 16-24 months. A rarer risk is a temporary low platelet count, called immune thrombocytopenic purpura, which can occur in 1 out of 40,000 children receiving the vaccine. The rarest risk is anaphylaxis, estimated to occur in one to two per 1 million children.

More than a dozen studies have confirmed that there is no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Only one death has ever been linked to the MMR vaccine in the U.S., a 21-month-old who developed measles inclusion-body encephalitis eight months after vaccination in 1999.

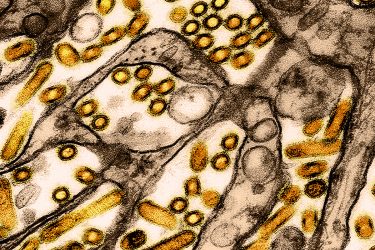

How contagious is measles?

Measles is the most contagious human disease known. It’s airborne, and the droplets remain in the air up to two hours after an infectious person leaves an area. At least 90% of susceptible (non-immune) people exposed to the virus will develop measles.

The contagiousness (or transmissibility) of a disease is calculated as the basic reproduction number, expressed as the R-naught (R0). The R0 refers to the number of susceptible people a single individual with the disease will infect during the course of their illness. The number isn’t static — it can shift based on multiple factors — but for measles, it’s roughly 12-18.

What is the incubation period and infectious period for measles?

People infected with measles show the first symptoms, usually a rash, approximately 10-14 days after exposure to the virus. However, they are contagious starting about four days before the rash appears until about four days after the rash appears.

Measures taken to quarantine and track cases must take this math into account, so you should be prepared to ask public officials and others managing an outbreak to answer questions about exposure windows for people who were at locations where an infected individual was present.

What is the herd immunity threshold of measles and how does it relate to current vaccination coverage?

The herd immunity threshold is the percentage of residents in a community who must be immune to a disease to prevent its spread through the population. Since measles is so contagious, the herd immunity threshold is high at 95%.

Based on the vaccination coverage of U.S. kindergarteners in the 2024-2025 school year, only 92.5% received both recommended doses of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, a drop of 0.2% points from the 2023-2024 year. The average national vaccination rate is therefore below the herd immunity threshold and still declining. Further, that 92.5% represents the average, not the rate in individual states or communities. Rates vary considerably between and within different states; journalists can download this Excel file from the CDC showing how many kindergarteners lacked documentation of the MMR vaccine to see the numbers for their state.

In California, for example, which in 2016 eliminated non-medical exemptions for school vaccination requirements, 96.1% of kindergarteners were fully vaccinated against measles. West Virginia, which has never had non-medical exemptions, had the highest rate, 98.3%, in 2023-2024, but the state did not report their rate in 2024-2025.

On the flip side, only 78.5% of kindergarteners are vaccinated against measles in Idaho (a drop from 79.6% last year), which restricted non-school vaccine mandates in spring 2025 and previously halted the health department’s ability to administer any Covid-19 vaccines.

Within states, immunization coverage can also vary widely, especially in states with looser laws on vaccination requirements. It’s the pockets within a state — such as the highly unvaccinated region of Texas where the largest outbreak started — that indicate a community’s susceptibility to an outbreak.

Why is measles returning at such high numbers when it was eliminated?

The answer is both simple and complex: in simple terms, vaccination rates have declined, creating large pockets throughout the country where measles can and has easily gained a foothold. But the reasons for the drop in vaccination is far more complex.

It’s important to familiarize yourself with the complexities and nuances of vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal, and anti-vaccine advocacy before reporting on any of these since many misconceptions about them exist. Inadvertently propagating those misconceptions through well-intentioned reporting, or approaching a story on vaccine hesitancy without a strong foundation in the research and nuances, can inadvertently contribute to additional vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccine sentiment.

For an excellent primer on these issues, check out SciLine’s package on “How to cover vaccines responsibly,” which includes the following:

- Why it’s urgent that journalists understand the science behind vaccines, disinformation

- Covering vaccines: Understand the science, be thoughtful about framing

- For journalists covering vaccines, advice on understanding hesitancy

- Covering vaccine mandates and policy in a polarized community

- Reporting on common vaccine conspiracies and misinformation

- Pulling back the curtain on religious and cultural resistance to vaccines

- Understanding vaccines: Use these free social-friendly graphics

- Vaccines in the news: What to cover and how

- Vaccine safety tip sheet

What are the complications and death rate of measles?

Common complications include ear infections, diarrhea and pneumonia. More serious complications include encephalitis (in approximately one of every 1,000 cases) or severe pneumonia (the most common cause of death in children with measles).

In the U.S., an estimated one to three children per 1,000 with measles will die from complications of the disease during acute infection. That said, three people died of measles last year out of 2,267 total cases, including two children, so these numbers are only approximations.

The most serious — and terrifying — complication of measles is subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a rare, progressive neurological disorder that develops when the measles virus invades the brain and nervous system and causes inflammation. The subsequent neurological impairment causes memory loss, irritability, language loss, mood changes, cognitive decline, vision loss, seizures, and eventually coma and death.

SSPE is always fatal as there is no cure, but symptoms do not present until seven to 10 years after the infection, and deterioration lasts an average one to three years, rarely beyond four years, though at least one case lasted 13 years. SSPE had previously been thought to occur in only five to 10 out of 1 million people who had measles, but the 1989-1992 measles outbreak resulted in a rate of four to 11 cases out of 100,000 cases. Another study in 2016 found a rate of one in 1,367 cases, with an even higher rate (one in 609) among children who had measles before age 1. The time to presentation was also longer, an average of 9.5 years.

How does measles harm the immune system?

One feature about measles that was only somewhat recently discovered and thought to be unique relative to other viral diseases is that it can cause “immune amnesia.” That is, a measles infection can cause the immune system to “forget” how to fight other diseases it’s already learned to fight: it destroys many of the immune systems’ existing antibodies to other diseases, so it no longer recognizes those pathogens. This phenomenon was first described in a 2015 study in Science, which found that measles can cause an increase in overall childhood infectious disease deaths even among those who initially survive the measles infection because the disease disables immune memory until reinfection or re-vaccination.

Is measles worse for kids or adults?

Measles can be serious at any age, but children under age 5 and adults over age 20 are at greater risk for complications. Others at higher risk include those who are pregnant or immune-compromised. Children under age 2 appear to be at higher risk for the compilation of SSPE.

Does vitamin A treat or prevent measles?

The only way to prevent measles is vaccination. The primary treatment of measles is supportive care, which means treating the symptoms and complications. There is no cure or direct treatment for measles. Vitamin A cannot prevent measles. In fact, cases of vitamin A toxicity have been reported in west Texas as Kennedy was inaccurately and irresponsibly promoting vitamin A as a way to prevent the disease.

Measles does, however, deplete the body’s stores of vitamin A, and the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases does recommend that physicians administer an age-appropriate dose of vitamin A to children hospitalized with measles, but it should not be administered by caregivers without a doctor’s recommendation or supervision.

Who needs a booster for measles?

Two doses of the MMR vaccine have been recommended for children since 1989. Most people born between 1957 and about 1983 likely only received one dose and would be eligible for a booster. People born before 1957 are presumed to have had a childhood infection and be immune. Those who got a vaccine between 1963 and 1967 may have received a less effective vaccine and might want to consider a booster.

Some physicians may advise people to check their titers (antibodies) to find out whether they are immune to measles before getting a booster. However, the MMR vaccine induces two types of immunity, only one of which is antibodies, so titers can be low even in people who are protected. Titers are therefore not necessarily clinically useful for determining whether someone needs a booster.

See this Q&A in Scientific American and this Yale Medicine article for more on who needs a booster.

Resources

- CDC measles outbreak dashboard

- Red Book Online for Measles

- South Carolina Department of Public Health and their measles dashboard

- “How to cover vaccines responsibly” tip sheets by SciLine

- Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at University of Minnesota and their Vaccine Integrity Project

- State exemption policies for vaccination requirements

- Vaccination Coverage and Exemptions among Kindergartners (includes 2024-2025 data)

- Coverage with Selected Vaccines and Exemption Rates Among Children in Kindergarten — United States, 2023–24 School Year, MMWR from October 17, 2024, including state coverage rates (for comparison to this year)

- Measles can ravage the immune system and brain, causing long-term damage – a virologist explains

- KFF’s Race-Based Vaccine Myths Spread Amid Measles Outbreaks

- List and short summary of 25 studies showing no link between MMR vaccine and autism

- Clinical information on measles (The Yellow Book)

- Measles Clinical Diagnosis Fact Sheet for health care providers

- Expert Vaccine Analysis Team for experts on infectious disease and vaccines

- Infectious Disease Society of America

- American Academy of Pediatrics info on measles and their Healthy Children site for parents