Shingles affects one in three people in their lifetime, according to the National Council on Aging. A new study from the University of Southern California has found that the shingles vaccine may do more than just prevent painful rashes. It might actually be associated with slower biological aging.

But researchers say it’s too early to call the shingles shot an anti-aging intervention.

Vaccinated people showed improvements in biological aging markers equivalent to several months to years, depending on the specific measure used. The benefits appeared strongest in three key areas: reducing inflammation, slowing molecular aging processes and improving overall biological health.

Using data from nearly 4,000 older Americans in the Health and Retirement Study, researchers discovered that people who received the shingles vaccine showed signs of slower aging across multiple biological systems. Specifically, vaccinated people had lower levels of chronic inflammation, which is linked to heart disease, frailty and cognitive decline. They also showed slower epigenetic aging, a measure of how quickly cells are deteriorating at the molecular level and better overall biological health markers compared to those who hadn’t been vaccinated.

Why this matters

In light of ongoing vaccine hesitancy and barriers such as access, cost, and awareness among some older Americans, this study reinforces the benefits of receiving age-appropriate vaccinations.

Journalists can examine these barriers and misconceptions, look at current efforts and what health care providers, health systems, city and county health departments, and insurers can do to ensure that anyone eligible is aware of and has access to this vaccine.

For example, the CDC recommends the shingles vaccine for people 50 and older. Thanks to a zero cost-sharing policy under the Inflation Reduction Act, there was a noticeable increase in vaccine uptake by people on Medicare Part D compared with those who are commercially insured, the Pharmacy Times reported in fall 2024. Are there similar programs to offset costs for people on exchange or employer plans?

If the vaccine also provides aging-related benefits, this could strengthen the case for improving vaccine access and uptake, particularly among populations with historically lower vaccination rates.

Preventing shingles and more

The shingles vaccine works by keeping the varicella-zoster virus, the same one that causes chickenpox, from reactivating in the body. That virus sits dormant in nerve tissue after childhood infection, occasionally flaring up to cause shingles. Researchers suspect the virus may contribute to triggering ongoing low-grade inflammation even when it’s quiet.

Shingles not only cause blistering and a painful rash, but can lead to a long-term condition called post-herpetic neuralgia, or pain caused by damaged nerves. According to the Shingles Support Society, people over 50 are 15 times more likely to get it than those under 50, especially if they have another health issue like diabetes, a weakened immune system, an injury that can reactivate the virus, or suffer from chronic stress. Severe shingles can also lead to serious complications requiring long-term medication, hospitalization, limit daily activity and adversely impact quality of life.

And, researchers noted that by preventing those viral flare-ups, the vaccine may be reducing a condition known as “inflammageing,” a chronic, simmering inflammation that accelerates aging throughout the body.

“By helping to reduce this background inflammation — possibly by preventing reactivation of the virus that causes shingles — the vaccine may play a role in supporting healthier aging,” researchers wrote.

The vaccine might also work through trained immunity, a process where immune cells get reprogrammed to respond more effectively to future threats. Some recent studies suggest that the newer Shingrix vaccine can trigger these beneficial immune changes, according to the study authors.

The benefits appeared to follow different timelines depending on the biological system. Improvements in molecular aging markers were strongest within the first three years after vaccination, while reductions in inflammation emerged later, after four or more years. This suggests the vaccine may influence different aging processes on different schedules, however, that question was beyond the scope of the current study.

Study limitations

- This study only looked at people at one point in time — it didn’t follow people before and after vaccination. This means the findings show an association, not a causal link between the vaccine and slower aging.

- Researchers also tried to account for “healthy-user bias,” the phenomenon in which people who get vaccines tend to be wealthier, better educated, and generally healthier. They used statistical techniques to adjust for these differences, and the association still held.

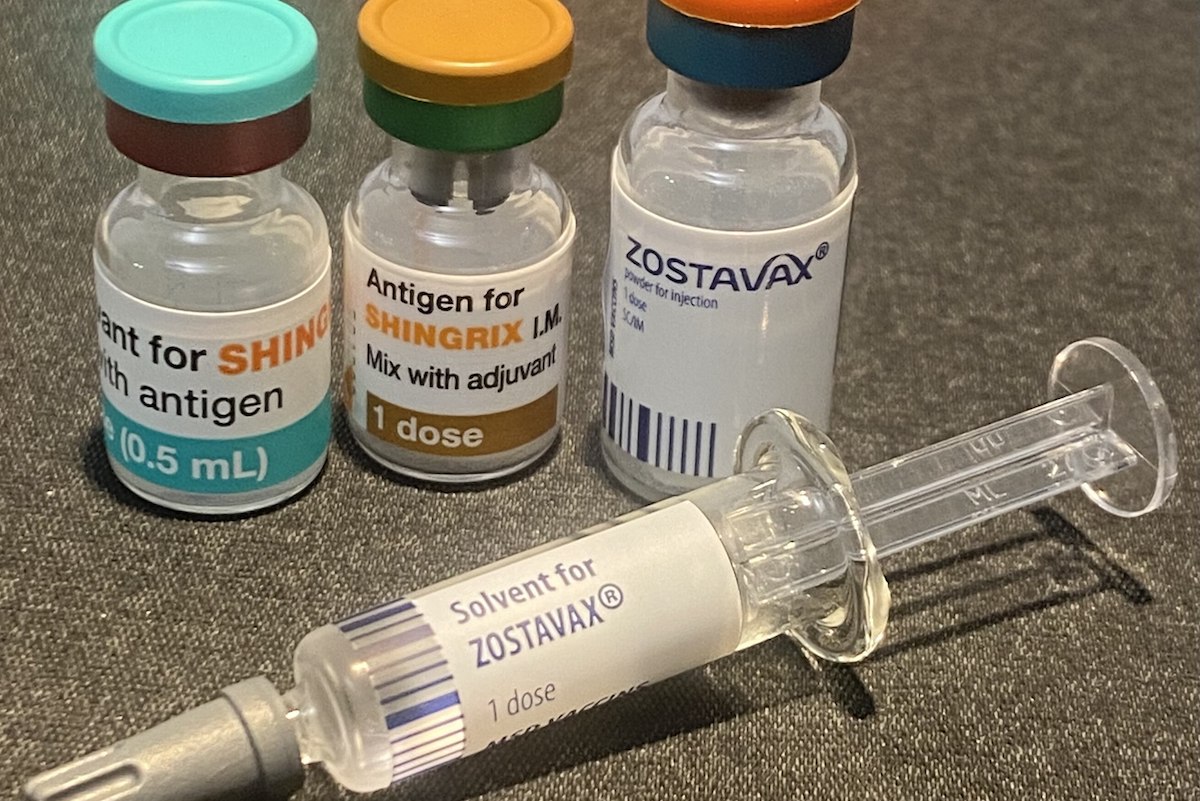

- The study only captured data from people who received the older Zostavax vaccine, which is less effective than the newer Shingrix vaccine introduced in 2017. Whether the newer vaccine has similar or better effects on aging is still being studied.

- Despite previous research linking shingles vaccination to reduced dementia risk, this study found no significant associations with brain aging biomarkers, or significant effects on cardiovascular health measures like blood pressure and pulse rate. This suggests the vaccine’s potential brain benefits may work through indirect pathways, such as reducing overall inflammation, rather than directly affecting brain tissue, the authors noted.

Promising patterns emerge

This research is part of a larger, emerging picture: vaccines might do more than prevent specific diseases. Recent studies have suggested the shingles vaccine may reduce dementia risk, while influenza vaccination has been linked to better cardiovascular outcomes in older adults.

If confirmed in future studies, these findings could reshape how we think about vaccines. Rather than simply preventing acute infections, vaccines might serve as low-cost tools for promoting healthy aging more broadly.

However, the authors stressed that more research is needed, particularly long-term studies that follow people before and after vaccination, and studies of the newer Shingrix vaccine, before anyone can definitively say the shingles vaccination slows aging.

“Further research is needed to determine whether such effects are transient or sustained, vary by vaccine type or timing, and whether they translate into clinically meaningful outcomes such as improved function or longevity,” the researchers cautioned.

In the meantime, vaccines may represent “practical, low-cost population-level” interventions for healthier aging, they said. But no one should consider them anti-aging treatments.

Resources

- The Shingles Support Society (UK)

- Everything you need to know about shingles (Yale New-Haven Health)

- Shingles Symptoms and Complications (CDC)

- Shingles Vaccine for Older Adults (National Council on Aging)

- Can you work with the shingles virus? (California Learning Resource Network)