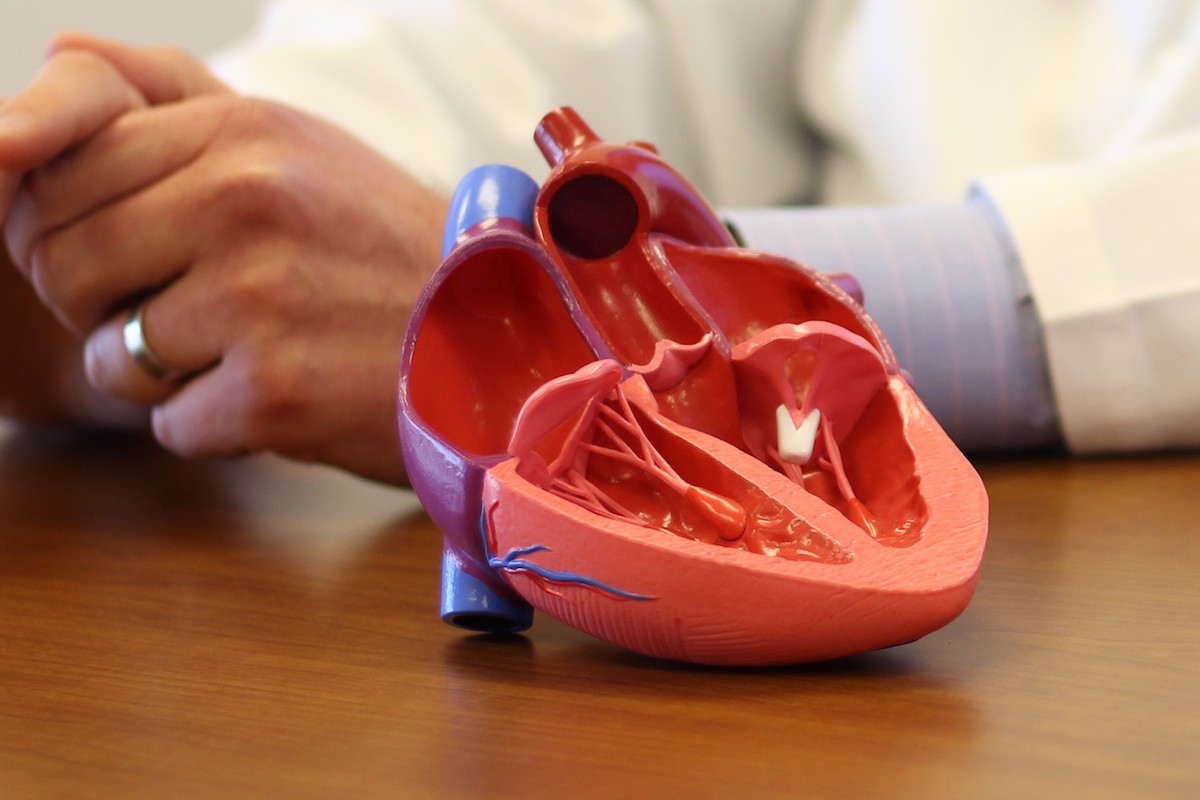

People with congenital heart disease are born with hearts that don’t resemble a typical organ. They may have holes between chambers of the heart, for example, or a complete absence of one or more valves, according to the American Heart Association, necessitating surgical procedures to correct such defects.

But because the conditions are rare (impacting about 1% of births each year) and present with highly individualized anatomy, some surgeons have been turning to a new tool when planning operations: 3D printing.

Journalists can find interesting stories by speaking with surgeons or other clinicians about how they are incorporating 3D-printed models of the heart in their procedure planning, or by interviewing patients about how the tools help them understand anatomy and what the procedure will entail.

How it works

Kanwal Farooqi, M.D., a pediatric cardiologist and director of cardiac 3D printing at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City, described how she incorporates 3D models in a recent webinar for Becker’s Hospital Review.

First, specialists such as Farooqi incorporate images from patient CT scans, MRIs and echocardiograms and, through a process called segmentation, translate cross-sections of those images into precise dimensions for the 3D printer.

Just as people use GPS navigation systems for directions, the 3D models provide an added depth perspective surgeons can use to guide where they can insert catheters or place patches. It also ensures that surgical teams have all necessary materials before starting an operation and makes them more confident about what they can achieve through surgery, information that is helpful when counseling families in presurgical visits, experts at Johns Hopkins told me last year while I was reporting an article for one of the medical center’s publications.

“We see everything in 3D, but most of our imaging techniques are usually 2D. We have to reconstruct that 3D part in our head,” Sruti Rao, M.D., a pediatric cardiologist, told me.

Models can be printed using different materials, from a hard resin allowing clinicians to assign different colors to different parts of the heart, or a flexible clear silicon allowing specialists to practice routing patches. Models also can be made at different scales, allowing for a larger replica of a newborn heart for better study.

Cardiologists and heart surgeons also can use the models to plan placement of ventricular assist devices (heart pumps), Farooqi said, and procedures such as heart valve replacements, printing models that mimic the physiological qualities of real valves, the Hindustan Times reported.

Models are also being incorporated into education, both of patients/families and of medical students and other trainees, Farooqi said. “It’s not atypical to see me carrying a number of 3D models in my white coat with me when I go into the ICU or when I’m rounding,” she said.

3D printing in orthopedics — and other areas of medicine

Orthopedic surgery is another area that has been embracing 3D-printed models. For example, the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City has been using 3D printers to manufacture custom joint replacements when standard devices won’t work for a particular patient’s anatomy, according to a hospital news release. Orthopedic surgeons with the hospital’s Complex Joint Reconstruction Center see patients with severe deformities, massive bone loss or failed joint replacements needing to be redone, where custom implants made from titanium can restore function and mobility, or even save a limb, the writeup said.

3D printing enables the creation of patient-specific surgical guides, making some challenging procedures more precise, implants that are better fit for complex anatomy and anatomical models for better surgical planning, Michael Rivlin, M.D., a hand and wrist surgeon at Rothman Orthopaedics in Philadelphia, told Becker’s Spine Review. In the postoperative period and during rehabilitation, he said, 3D printing allows for custom-fit devices like braces, splints and casts that provide superior comfort and functionality for patients.

Additional specialties are making use of printed models for surgical planning, too. Pediatric otolaryngologists at Seattle Children’s Hospital made a 3D model of the airway of an infant girl with right bronchial stenosis, a condition where the breathing passage leading to the lung is very narrow, KIRO 7 News reported. They used it to practice the procedure before treating the patient.

Other areas of medicine using 3D models include: general surgery, such as to plan tumor or kidney stone removal; head and neck surgery, such as to plan repair of jaw defects; neurosurgery, to visualize blood vessels when planning complex operations; urology, to simulate renal and prostatic cancer surgeries; and anesthesiology, to plan airway management, according to a review paper in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Resources

- Inside an In-Hospital 3D Printing Lab: How Columbia University Medical Center Uses Anatomical Models to Plan Complex Cases – webinar from Becker’s Hospital Review

- Improving Heart Surgery with 3D Printing – Johns Hopkins

- 3D printing becoming ‘standard practice’ in orthopedics – Becker’s Spine Review

- Seattle Children’s Hospital uses 3D printing to save lives – KIRO 7 News

- Custom 3D-Printed Orthopedic Implants Transform Joint Replacement Surgery – Newswise

- The Roll of 3-D Printing in Planning Complex Medical Procedures and Training of Medical Professionals – International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

- The future is now: 3D-printed heart valves may improve surgery outcomes – Hindustan Times