More than 1 billion people live in areas where the heat and the humidity will surpass the survivability limit by the end of this century. For comparison, the COVID-19 pandemic killed an estimated 15 million people in its first two years, according to the United Nations. So, such extreme heat could be orders of magnitude worse than the pandemic in terms of mortality if the world does not prepare for temperature spikes and quickly reduce carbon emissions.

The survivability threshold for an athletic, fit human body is pretty consistent across studies: 95°F — but that’s not the air temperature you would read on your weather app. It’s the wet-bulb temperature, which is the temperature reading at 100%humidity. Many of us have survived a 95°F day, measured as the air temperature reported on our weather apps — even though that heat level does pose risks for outdoor laborers or vulnerable populations. But above a wet bulb temperature of 95°F, the body can’t survive past about six hours, because sweat no longer cools the body.

In desertous places, a wet-bulb temperature of 95°F will be a much higher air temperature, whereas in humid places it will be much closer to 95 degrees. That’s why we know to check the heat index on our weather apps. But the wet bulb temperature is a more accurate measure of safety. The heat survivability threshold is the point where the laws of physics determine whether a human body can survive. And to further complicate things, elderly people, pregnant people and infants and children all are at risk at wet-bulb temperatures lower than 95°F, which have not been well studied.

The hottest places on Earth have already exceeded the heat survivability threshold, at least for short periods of time. Places in the Persian Gulf, for example, have logged some of the hottest temperatures. While these heat waves are dangerous and concerning, countries like Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Saudi Arabia are well off, with widespread electricity and cooling available. The risks are rising for such events to hit places that do not have these resources and are vastly underprepared.

“What happens when that comes to northern India and Bangladesh?” Anna Bershteyn of NYU Grossman School of Medicine asked AHCJ’s fall summit audience in November. “Bangladesh has the world’s largest refugee camp, where you have massive informal settlements with way too many people to evacuate.”

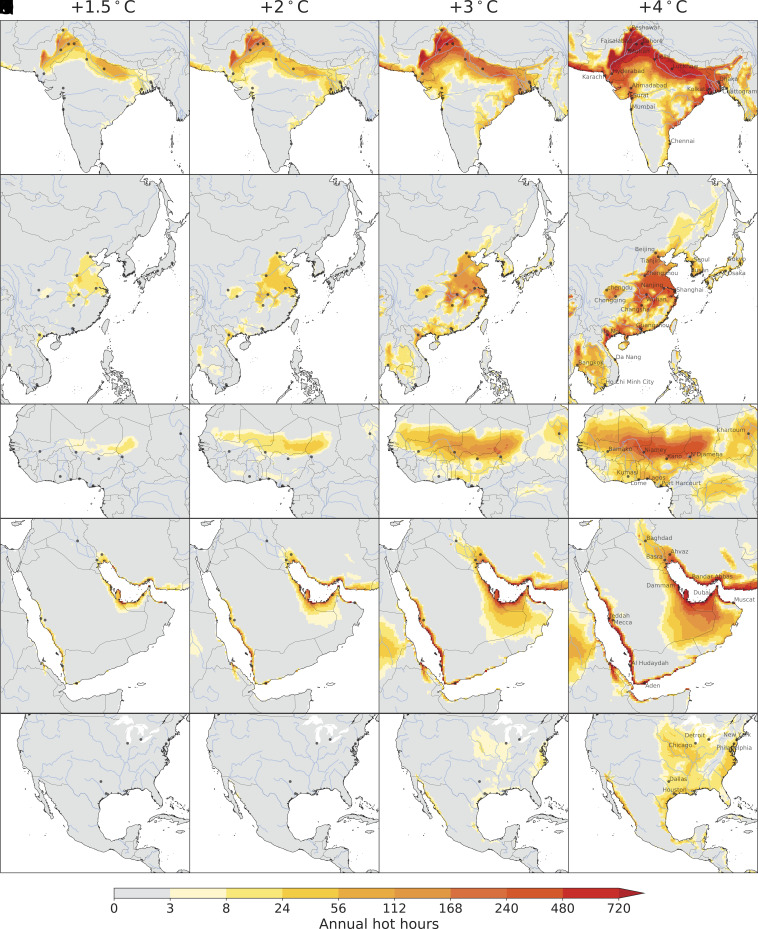

We know that the occurrence of heat events that exceed the survivability threshold will worsen because of climate change. But how bad they get depends on how much climate change the world can avoid by reducing carbon emissions more quickly. At 2°C of warming in the average global temperature, southern Pakistan, northern India, Bangladesh, North Africa and the coast of the Arabian Gulf start experiencing heat events that surpass the survivability threshold. At 4°C of warming, about half of the United States will start experiencing these extreme heat events.

Preparing for the Hottest Weather

The good news, Bershteyn said, is that we have time to prepare. “We don’t know exactly how much time we have, because temperature is so stochastic,” she explained at the fall summit.

Through Project HEATWAVE at NYU, which Bershteyn directs, she and her team plan to build a digital policy lab that will let policy makers play out what happens when they apply different interventions under different warming scenarios to help them make decisions about preparation within this uncertain environment.

Bershteyn said we need improved air conditioning and medical innovations. “We know what medications make people more prone to heat stroke, but we don’t know what medications make people less prone to heat stroke,” Bershteyn said. “Is there something we could mass distribute in a heat emergency?” In settings where air conditioning is unavailable and evacuation is not possible, such an innovation could save many lives.

Researchers need to use this time to develop new tools, according to Bershteyn. “We just don’t have the technologies today that we need to save lives in that ‘Ministry for the Future’ scenario,” Bershteyn says, referring to the imagined event described in the first chapter of Kim Stanley Robinson’s climate fiction novel.

Unlike that book, our story isn’t yet written. How we use the time before climate fiction becomes climate reality will determine what the story of heat extremes looks like for billions of people.