Last month, New York Times political writer Ezra Klein posted an interview with top Democratic pollster David Shor, head of data science at Blue Rose Research, whose forecasts have highlighted important political patterns during a time when conventional wisdom has often failed. Although Klein’s interview angle is about what Democrats can learn from polling data, I found the information relevant for people in science journalism who want to reach bipartisan audiences in a deeply polarized information environment. Trump voters, people of color, young adults and nonvoters tend to be disengaged from traditional media, so journalists working in today’s information environment often struggle to reach these audiences.

“People who follow news really closely, who get their news from traditional media, who say that politics is an important part of their identity, they became more Democratic [over the past four years] in absolute terms,” says Shor. “But for people who don’t follow politics at all, they became a lot more Republican.” This pattern reinforces an information gap: People who consume news are more likely to be Democratic. Journalists need to be reaching everybody.

This pattern has particular relevance to people who report on science. The polarization around topics such as climate change has been studied for a long time, and vaccination has also become politically polarized in recent years. Speaking generally, Shor pointed out the global trend that people without college degrees are moving to the right, while college-educated people are moving to the left. Most science audiences are college-educated, and so, combined with the effects of national political rhetoric, science is becoming increasingly associated with the left, even though it affects everyone. As I listened to Shor and Klein’s discussion about what polls well with Americans, I kept thinking about how Shor’s data revealed science journalism angles that could reach bipartisan audiences.

Some of the most vulnerable people are not taking in information about how science is relevant to them. “It’s not just that New York Times readers are more liberal than the overall population — that’s definitely true — they’re more liberal than they were four years ago, even though the country went the other way,” says Shor. “And so there’s this great political divergence between people who consume all the news sources that we know about and read about, versus the people who don’t.” Although this problem may not seem new — political polarization in the information system has been recognized for a long time. Shor says that the patterns here are new. “There have been dramatic shifts in the media consumption habits of [the people who care the least about politics],” he says.

Many of the phenomena Shor highlights are well supported in a variety of research outlets. But his data graphics helped me put together a whole picture of media and demographic patterns that I hadn’t appreciated before. Below are five take-home points from this interview that I will be keeping in mind in my science journalism practices moving forward:

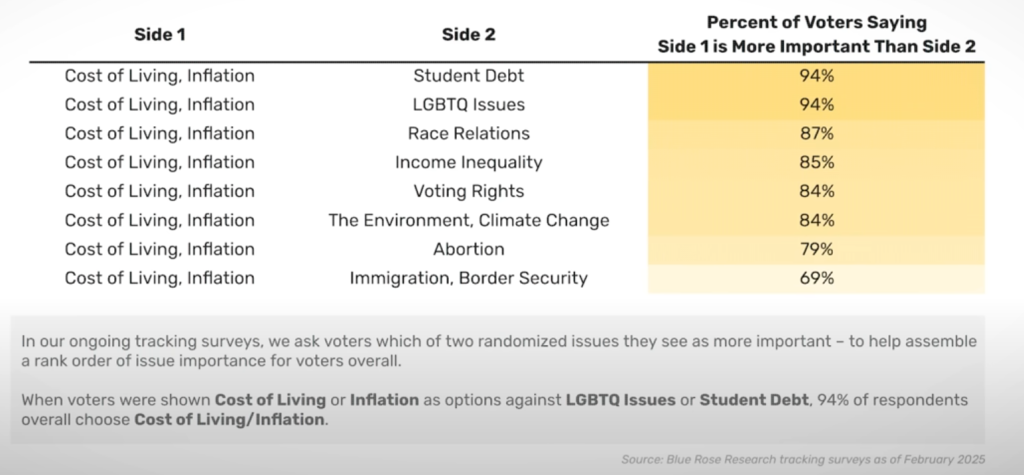

1. People distinguish between science issues and economic issues in their politics. People just aren’t connecting science issues like health care, mental health, climate change, the environment, and abortion to economic issues like cost of living and inflation. That’s despite the fact that the single biggest factor in inflation was the COVID-19 pandemic’s influence on supply chains and despite the fact that climate change and health care have myriad effects on everyday Americans’ cost of living.

These issues should be cross-partisan, and journalists can help engage audiences of many political persuasions by pulling together those two topics. But, “it’s very hard to get media attention on cost of living and the economy,” Shor acknowledges.

2. Cost of living and the economy are the most important issues to the audience that is disengaged from traditional news media, Shor says. Journalists and scientists — myself included — are failing to connect issues around democracy and science to everyday economic issues. Many of us have assumed that audiences could see the connections between the erosion of democracy and science with the erosion of the economic well-being of the working class. We need to make those connections explicit, repeatedly, in our reporting.

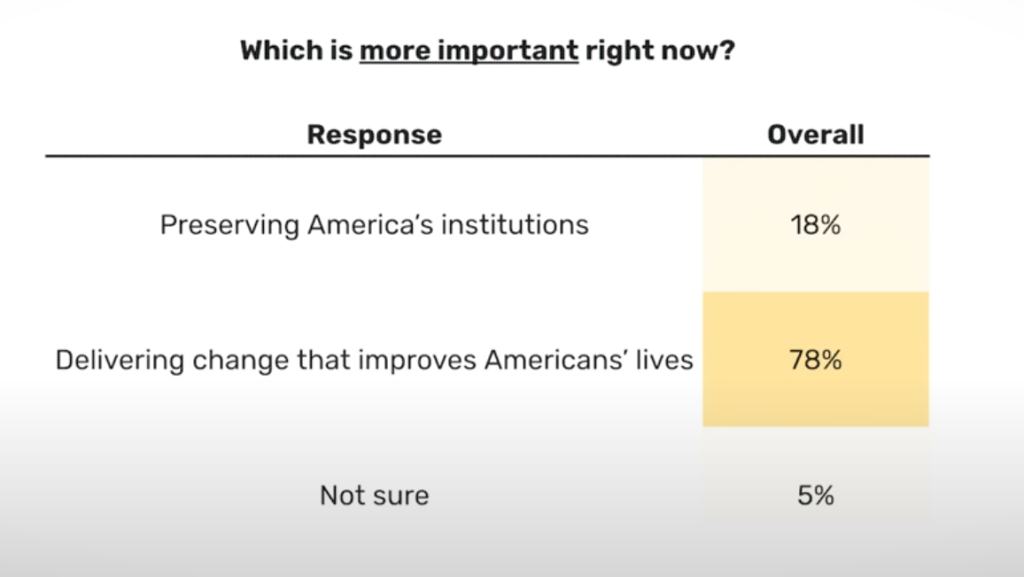

When “preserving America’s institutions” is pitted against “delivering change that improves Americans’ lives,” 78% of survey respondents chose the latter. (I personally refuse to answer questions like this, where the two options are so obviously related.) Nevertheless, what this survey result indicates is that journalists need to constantly point out how the erosion of America’s scientific and health care institutions is affecting Americans’ lives, especially when it comes to the cost of living.

“The kind of people who set media decisions at CNN or who work in politics are the kinds of people who are going to be much more concerned about [issues of democracy and authoritarianism] than working class folks are,” says Shor. Journalists can’t assume people understand how the erosion of democratic norms will affect their own livelihoods; it needs to be spelled out.

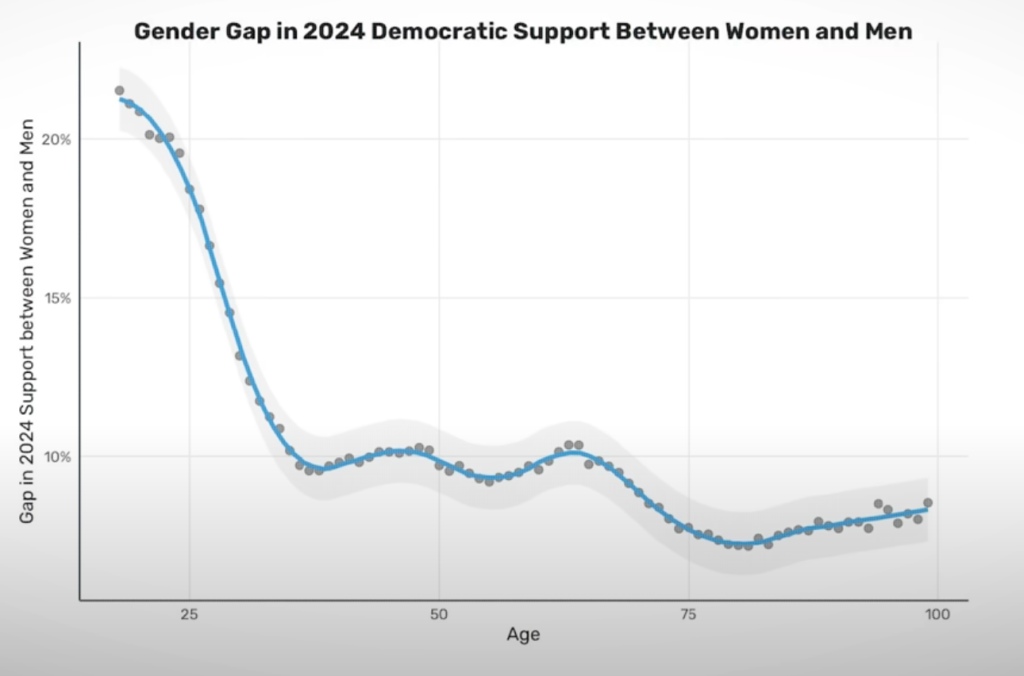

3. The gender gap among young voters has increased dramatically, and this phenomenon is global. This massive and growing gender gap indicates an information gap, potentially driven by algorithmic segregation on social media platforms. So, journalists are more likely to reach their own gender online, and media platforms need to represent all genders in order to reach the widest audience.

I personally don’t want my work to reach mostly women. I like engaging with men and gender-diverse audiences, too. The more that journalists can cross this divide — engaging with and resharing content that disrupts rather than reinforces this gender gap — the more we can disrupt this disturbing information segregation.

4. Include coverage that speaks to Zoomers’ values (people between the ages of 13 and 28). “We’re in the midst of a big cultural change that I think that people are really underestimating,” says Shor. “If you look at Zoomers, there’s a lot of interesting ways that they’re very different in the data. They’re much more likely than previous generations to say that making money is extremely important to them.

They have a lot higher levels of psychometric neuroticism than the people before them … All I can say is, young people today seem to have fairly different values than they did 10 years ago.” What I immediately see a need for here is more reporting on housing affordability, mental health, cost of living and economic inequality, and how those issues intersect with one another and with other salient news topics.

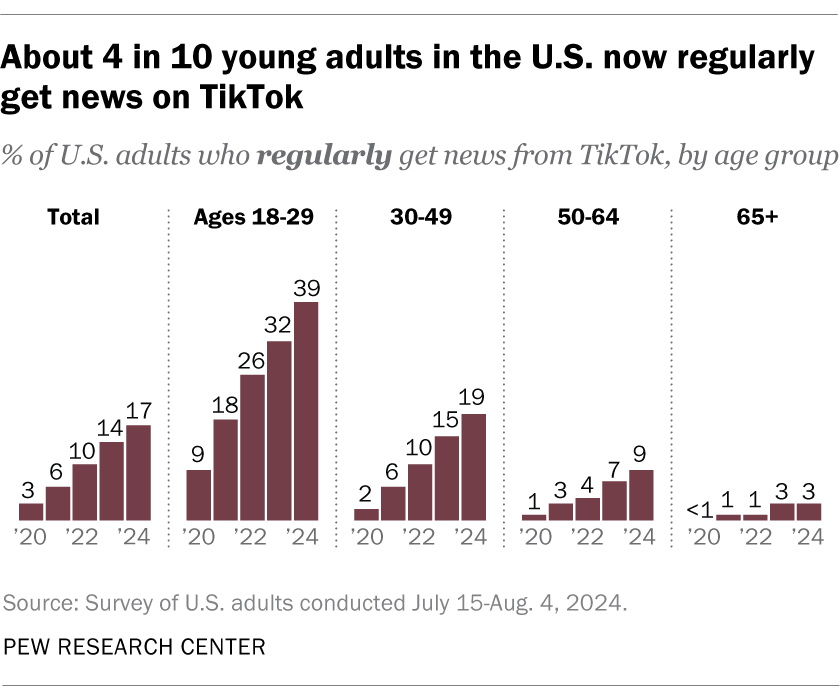

5. Keep an eye on TikTok. “The share of young voters who get their news from TikTok more than quadrupled in the last four years,” says Shor. “This is the biggest and probably fastest change in media consumption that has happened in my lifetime.” What’s more, Shor says, TikTok use was correlated with a change in partisan support, and his data indicate that TikTok was causal in some way.

“When you zoom in particularly to people who get their news from TikTok who don’t care very much about politics, this is a group that is 8 percentage points more Republican than they were four years ago, and that’s a lot,” says Shor. Klein and Shor discuss potential causes, including the platform’s algorithms, but right now it’s unclear why this change happened. “I think that TikTok represents something fairly radically different than social networks that came before it,” says Shor.

“TikTok is the first social media platform that is really truly decentralized. It’s not based on follower graphs. If you look at Reels or Twitter or other platforms, how many people see a piece of content is highly correlated with how many followers that person has. TikTok is a lot more random, and there’s very interesting machine learning reasons for why. But I think it allowed a lot of content that never would have gotten a lot of views on Twitter or television to suddenly escape containment and get directly into the eyes of people who don’t care much about politics … For whatever reason, this big change really did help Republicans, and it’s just an example of how the world has really changed a lot.”

There’s much to discuss here around regulating social media, of course. But given that that’s unlikely in the United States in the deregulatory, pro-tech environment of the current administration, journalists can pay more attention to what is doing well on TikTok, especially among politically disengaged groups.

“I think that TikTok is genuinely strange relative to platforms before it in that its audience is more politically disengaged and more working class,” says Shor. TikTok has entirely changed the information environment for young people, politically disengaged people, and working class people.

Of course, reaching a broad audience is always an uphill battle in today’s fractured and politically polarized media environment. Ultimately, individual journalists can only do so much to disrupt the power imbalances, fragmentation, and polarization in our media system. But at the very least we can avoid playing into divides when they become apparent.