During my research on the reasons why health reporters should be covering malaria, I spoke with William Moss, a professor of infectious disease epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Moss, an expert particularly in malaria and measles. He highlighted three big reasons malaria deserves attention from the media — starting with the fact that it’s still a major cause of death of children.

“There’s malaria death every minute,” Moss told me.

While most reporters are aware of the burden of the disease, they may not realize the other two reasons Moss highlighted: progress on fighting the disease has stalled for myriad reasons, and new tools are on the horizon that might hold promise of easing the stalled progress. Here’s an edited version of that conversation, rich with insights about the disease and story ideas for reporters to pursue.

This conversation was lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Can you discuss some of the reasons why progress has stalled in beating back malaria in recent years?

Reasons for stalling progress include insecticide resistance in the mosquito and drug resistance in the parasites. These are both really complex organisms that continue to evolve and evade our tools, so we’re in dire need of new tools to fight malaria. We do have these two new vaccines, RTS,S and R21. They’re quite similar in structure and how they work, but we’re just beginning to see kind of the rollout and scale up of these vaccines. They’re not the ideal vaccines — we still need better vaccines — and we need strategies to prevent malaria transmission outdoors.

A lot of our insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor residual spraying are vector control strategies that are effective, but they largely target indoor transmission, and we’ve seen changes in the behavior of the mosquito to bite more outdoors, for example.

There are a number of new technologies on the horizon, whether it’s sterile males (also see here, here and here) or genetically modified mosquitoes (also see here, here, and here) or altering the microbiome of the mosquitoes. These have not yet really been tested on a large scale.

With climate change, we’re still figuring out what the impact of that may be. It can lead potentially to increasing breeding sites and conditions for mosquitoes to breed, but it also can lead to profound drought that could wipe mosquito populations out.

To what extent does malaria pose a threat within the U.S.?

Most people probably don’t realize that malaria was endemic up the east coast of the United States in the early 1900s, and we still have the vectors here that can transmit malaria. We’re not going to see outbreaks of malaria in the United States, but we will have these small pockets, clusters like we had in Florida and Texas or the isolated case in Maryland.

The one in Maryland is particularly interesting, because it was Plasmodium falciparum (the most deadly malaria parasite), whereas the others were Plasmodium vivax. I don’t want to overstate this, because, again, malaria will not be a big problem in the United States. But that it can happen here, and then can be transmitted, was what was so unusual about these recent cases. That was the first local transmission in about two decades.

Can you talk a little bit about what the limitations of the vaccines are and why it’s so hard to make a vaccine against malaria?

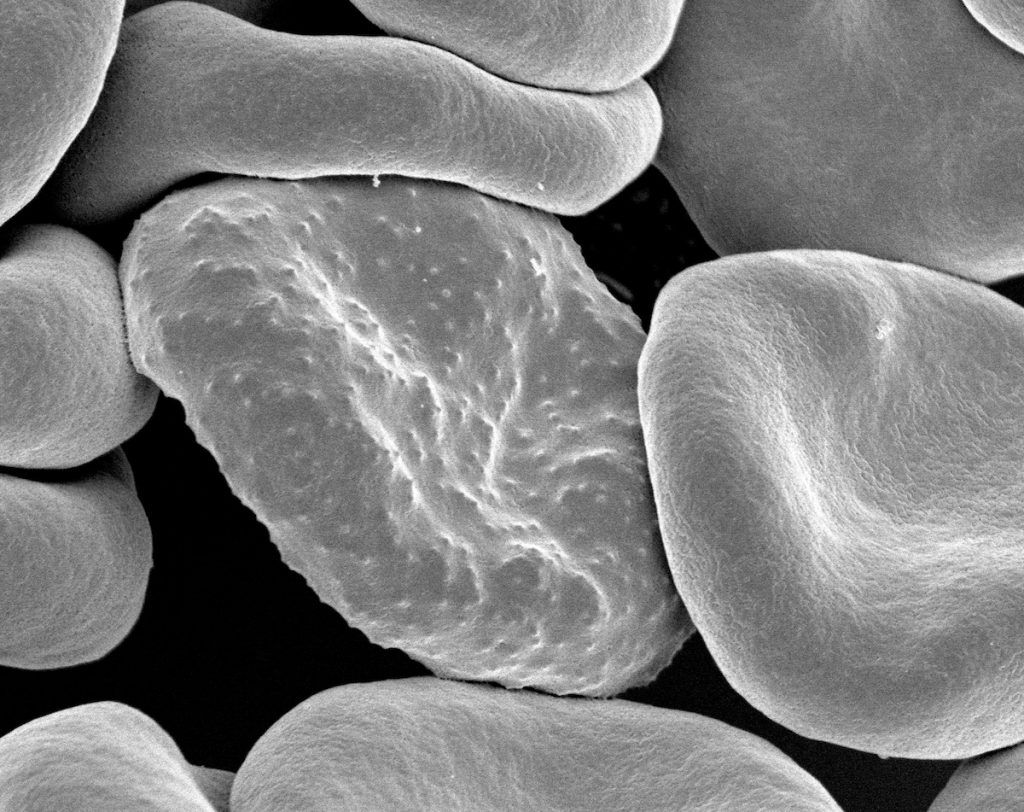

Plasmodium parasites [which cause malaria] are complex unicellular organisms that have chromosomes, and they have a very complex surface coat that can change. It’s evolved mechanisms to evade our immune system, and thus, it can evade vaccines. It’s very hard to develop a single vaccine that’s going to really prevent infection.

Another thing is that vaccines have to be extremely efficacious because one of the amazing things about the lifecycle of Plasmodium is that they have these massive amplification steps in our bodies. So if one spore gets through into the liver, it will form 10,000 merozoites, so there’s this huge amplification step, and then it is amplified again in the red blood cells. To prevent disease from happening, you almost have to completely block all the sporozoites.

For diseases where the natural infection induces lifelong immunity — measles is the classic example — you can replicate that with a vaccine, but for infections like HIV or with Plasmodia, where even natural infection doesn’t induce sterilizing immunity, or complete protection, it’s just really a big ask of a vaccine to do better than nature.

How do the current malaria vaccines work?

Both the RTS,S and R21 vaccines target a protein on the sporozoite. The sporozoite is the form of the parasite that’s injected by the mosquito [before the parasite reproduces and creates many more organisms in the body]. The sporozoite is an ideal target because the number of parasites you’re targeting is small. The vaccines basically induce an immune response to the surface protein on the sporozoite and prevent those sporozoites from entering liver cells, which is the next stage in the development of the parasite in humans.

There are other vaccines in development that target the red blood cell stage. There are interesting vaccines that target the gametocyte, which is the sexual stage of the parasite that’s actually transmitted, that the mosquito takes up and then [goes through] a developmental process in the mosquito. Those are called transmission-blocking vaccines. At some point, I imagine we might see a combination vaccine that targets these different stages, maybe the sporozoite, the red blood cell stage and the gametocyte sexual stage.

Malaria was successfully eliminated in the U.S. primarily through outdoor vector control. Why has that kind of outdoor vector control not been successful in other countries where malaria is endemic?

It’s an issue of economics and malaria being a disease of poverty. I’ll give you an example. I worked on malaria in northern Zambia, where the transmission is probably as high as anywhere in the world. It’s just swampy, and in the United States, and in the Roman Campagna, the swamps around Rome, they were able to drain the swamps and control irrigation systems to minimize effective breeding. In an impoverished area in rural Sub-Saharan Africa, where it’s just swamps everywhere, it’s just too big a task to try to drain those areas. They just don’t have the resources and the ability to do it. It’s largely just the enormity of the problem and the logistics.

There is a lot of work on what are called spatial repellents, and, you know, actually my colleague here, Conor McMeniman, is studying what odors of a human body attract mosquitoes and being able to either develop repellents based on that or developing baits where you attract mosquitoes to kill them. Up in northern Zambia, in some households, we can capture 1,000 mosquitoes in one night.

The real advance is screens. Air conditioning helps because it allows people to close off their household in hot weather and stay indoors, but in rural, Sub-Saharan Africa, where it can be very hot in some places, people have these open eaves under the roof, and if you don’t have air conditioning and you don’t have screens, you have to keep your window open to be able to sleep.