If statistics tell a story, the one about the staggering cost of health care in the U.S. starts with chronic condition trends. According to the CDC, 90% of the $4.1 trillion that we spend on health care in the U.S. goes to treating diabetes, depression and other chronic conditions that are more common among some people of color, who represent more than a third of the population.

As some groups age faster than others — census data show that Hispanic Americans are getting older more rapidly than non-Hispanic populations — policymakers at all levels of government are faced with tough funding decisions related to access to care and insurance programs. Federal, state and local lawmakers hope that broader social and economic policies that are being adopted today will help promote health equity, and undo the harm of discriminatory policies from past decades.

It’s not difficult to see what’s coming. Since most non-white people are developing chronic conditions at younger ages compared to their white counterparts, they’re living with these conditions longer, putting more strain on the health system in both use and cost, with some groups, notably Black and Indigenous people, dying younger than those who remain healthier into older age. In 10 or 20 years’ time, these trends will squeeze Medicare and Medicaid even further, a story journalists should follow closely.

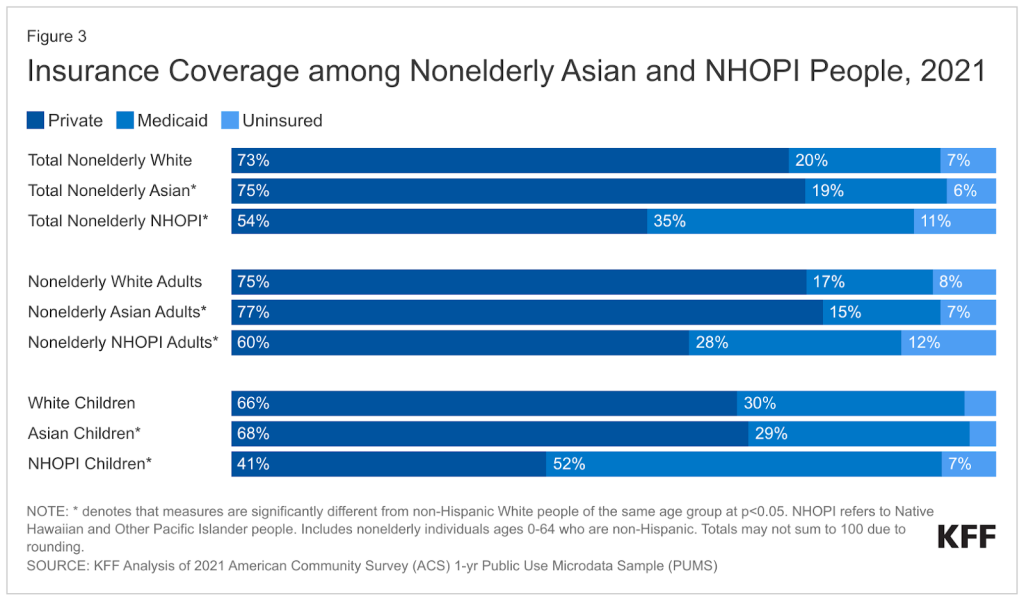

Federal data show that there are notable differences in the health profiles of U.S. racial and ethnic groups. For example, Black, Hispanic, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander adults are more likely than their white counterparts to say they are in fair or poor health. And the data show a larger proportion of adults ages 18-64 in those groups are uninsured.

According to a 2023 KFF analysis of public health statistics and census data, researchers found that Black, Hispanic and Indigenous people fared worse than white people across the majority of examined measures of health and health care and social determinants of health, critical influences on people’s access to providers and experiences and attitudes about medical care. Asian people fared the same or better than their white counterparts on most measures.

While there was some variation in this data, for certain types of cancer screenings and health measures, possibly due to improved care among certain subsets of these populations, among most non-white, non-elderly demographic groups, the analysis found:

- Greater lack of health insurance.

- Lower rates of key preventive care and screenings.

- Less access to care and regular health providers.

- Higher infant mortality rates.

- Increased incidence of food insecurity.

- Greater likelihood of self-reported fair or poor health status.

For purposes of this article, we identified racial and ethnic groups as non-Hispanic white (white), non-Hispanic Black or African American (Black), non-Hispanic Asian (Asian), not-Hispanic Native American and Alaska Native (Indigenous or Native American and Alaska Native), non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, (Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander) and Hispanic.

Tools to take a closer look at national, state and local trends

This interactive mapping tool of Medicare disparities, pinpoints national state, and county areas of variance between subgroups of Medicare enrollees in chronic disease incidence, health outcomes, use and social determinants of health such educational attainment and health access and quality. It is critical to understand why access to providers and services and insurance coverage alone doesn’t guarantee people will have better health outcomes.

Some policymakers have taken notice. In an opinion piece in The Hill, FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, M.D., and Haider Warraich, M.D., senior clinical advisor for chronic disease to the commissioner — both cardiologists — wrote “the U.S. is suffering from lower life expectancy than comparable nations.” They cited chronic disease as a major contributor, with many of the people most likely to need evidence-based care not receiving it. This leads to “the unintended consequence of widening the gap between the haves and the have-nots.”

And, an analysis by a team of Yale researchers found 1.63 million excess deaths in the Black population compared with white Americans, representing more than 80 million excess years of potential life lost. The study, published in JAMA in 2023, pointed to a pressing need to make health equity a reality, and for policymakers and clinicians to address structural racism and health disparities. According to researchers, since the pandemic, the U.S. has moved backward in closing the disparities gap, leaving patients no better off than they were in 1999.

But it will take more than a few studies and op-eds to address the widening gap in health equity among minority populations, and the increasing incidence of chronic diseases among younger, non-white adults.

Findings from a recent investigation into stroke trends in Ohio and Kentucky showed that the rate of new cases had decreased in Black people over that time. Still, the researchers said that “Black:White disparities have not decreased over a 22-year period, especially among younger and middle-aged adults, suggesting the need for more effective interventions to eliminate inequities by race.”