Editor’s note: This article has been updated to correct an error in describing language that stigmatizes addiction.

Do you cover drug addiction in your community? If so, you should be aware of how, among other things, word choice leads to more evidence-based, factual reporting. ReportingOnAddiction.org offers journalists some guidance.

Reporter Ashton Marra, M.S., and psychologist Jonathan Stoltman, Ph.D., co-founded the site to push back against news coverage of opioid addiction across Appalachia that Marra and Stoltman, the site’s co-directors, consider problematic. Among other suggestions, they want journalists to explain that opioid addiction is a “chronically relapsing brain disease,” not simply a disorder that a person can permanently recover from.

Marra, executive editor of 100 Days in Appalachia, and Stoltman, director of the Opioid Policy Institute, say ReportingOnAddiction.org is designed to help journalists with fact-checking, find quality sources and add more depth and context to their coverage.

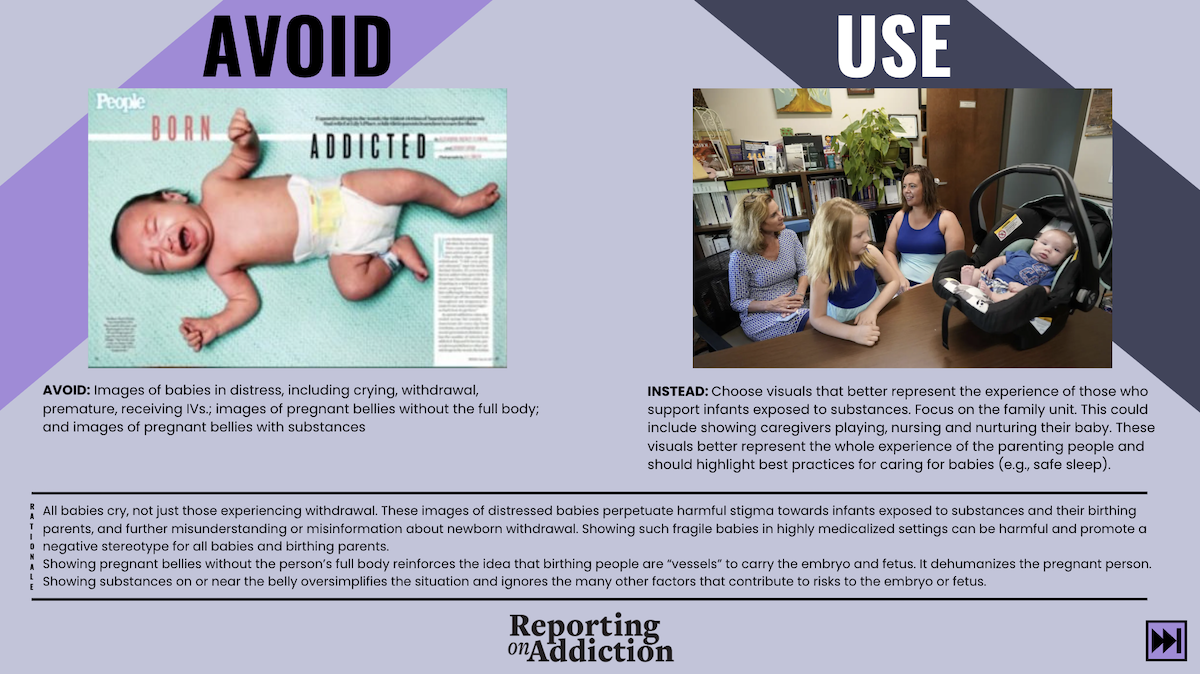

The site’s online language style guide, published in English and Spanish, suggests that resources for addiction treatment be included in every story and that coverage routinely include stories of “hope, healing and recovery.” The project also provides a visual style guide for photographers, videographers, graphic designers and multimedia content developers.

What follows is an abridged version of AHCJ’s interview with Marra and Stoltman, who have trained student journalists, journalism professors and reporters for The Wall Street Journal, KFF Health News, NPR and others.

What prompted the launch of your website and training program?

Marra: I was really offended by a particular story by a reporter who’d been newly, exclusively assigned to covering opioid addiction. The story itself … said there was a lack of response to the opioid epidemic in Appalachia, without acknowledging the lack of resources and lack of investment in our communities.

Initially, the idea was to come up with just a final sentence to get journalists to use at the end of their stories, similar to how the 988 number [for mental health emergencies] is being included at the end of some stories on suicide. Why are we not also pointing people with opioid addictions to help?

And that evolved into a much larger idea of not just a sentence, but actually helping journalists improve the reporting that they’re doing.

Stoltman: Regarding that news article, Ashton is being kind. Appalachia isn’t always represented in the best light. And the article felt very much like punching down: “What the hell’s going on in Appalachia?” … As opposed to really recognizing that there are very good people trying to do that work there. …

There are a lot of structural barriers to implementing some of the evidence-based solutions. And, unfortunately, there’s a lot of politicization around this. That just was not represented in the piece at all.

Why do you think a similar sign-off, on where to get help, hasn’t been attached to most new stories on opioid addiction?

Stoltman: Stigma and discrimination around addiction, generally, continues to be the case. It’s often treated, still, as an issue that is separate from health care. Even with suicide and mental health — routine inclusion of the suicide hotline in news stories started in mid-2000s — there’s been a long fight to bring those issues into broader health care.

Addiction still is this weird little gray space, including for some journalists and professionals in health care. Right now, some hospitals treat addiction, some hospitals don’t. It’s as if you have to go to a church basement to get services. Part of it is that it’s such a blind spot, including for journalists. But how great would that be for someone who has a family member affected by this to read that helpful information? Why can’t we do something to help them take that next step?

Many journalists — and, perhaps, veteran reporters in particular— may be especially mindful of keeping a strict line between reporting and what may look like advocacy. Has that caution been a factor?

Stoltman: We do hear that. And journalists are still trying to figure this out. But we don’t think, in this case, that it’s advocacy. It’s public health messaging.

You mentioned that harm reduction — providing safe places for addicted people to use their substance as, presumably, they are trying to quit — is a contentious issue for your region and other regions. How so? And why is that reality important to the opioid story?

Stoltman: With the syringe programs, politicians ended up eliminating funding and stripping providers of their licenses to offer free, clean syringes.

And, actually, the CDC had to come in because of a big HIV outbreak in the region. When you have a syringe service program, there’s not an HIV outbreak. All of this was covered really well by the local journalists, including at the Charleston [Gazette-Mail].

Taking a bigger step outside of Charleston, broadly speaking, access to opioid medications — naltrexone, methadone and buprenorphine — and services is a problem in a lot of places where doctors aren’t necessarily prescribing [medication-assisted treatment] and pharmacists aren’t filling those prescriptions. These are actually things that reporters should be doing a better job of covering.

Marra: We don’t have community clinics in the same way that a lot of places do. And, then, you pile on top of that the complications of our geography and our topography and being [in the] mountains.

These barriers block people’s access to resources, including health care. And addiction is absolutely a health care issue.

What’s your No. 1 tip, your cheat sheet for reporters covering the opioid epidemic?

Marra: Coverage of addiction is an ethical imperative for us as journalists.

I know that sounds extreme to some people. But I do genuinely believe that unintentional stigma in our reporting, that unintentional perpetuation of certain narratives … leads to people not being provided with care that they need. They die.

We’ve got to stop perpetuating these false narratives. We’ve got to stop telling these stories that harm an entire community of people.

Additional resources

- “The role of the media in promoting the dehumanization of people who use drugs,” published in March 2023 in The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse.

- “Reporting on Addiction: An Innovative, Collaborative Approach to Reduce Stigma by Improving Media Coverage and Public Messaging about Addiction Treatment and Recovery,” published in September 2022 in Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Written by Stoltman and Marra, it builds on their argument that words such as “in recovery” and “rock bottom” mischaracterize addiction.

- “Changing the language of addiction,” a commentary, published in JAMA in 2015.