Editor’s note: The study’s findings were disputed by government data experts.

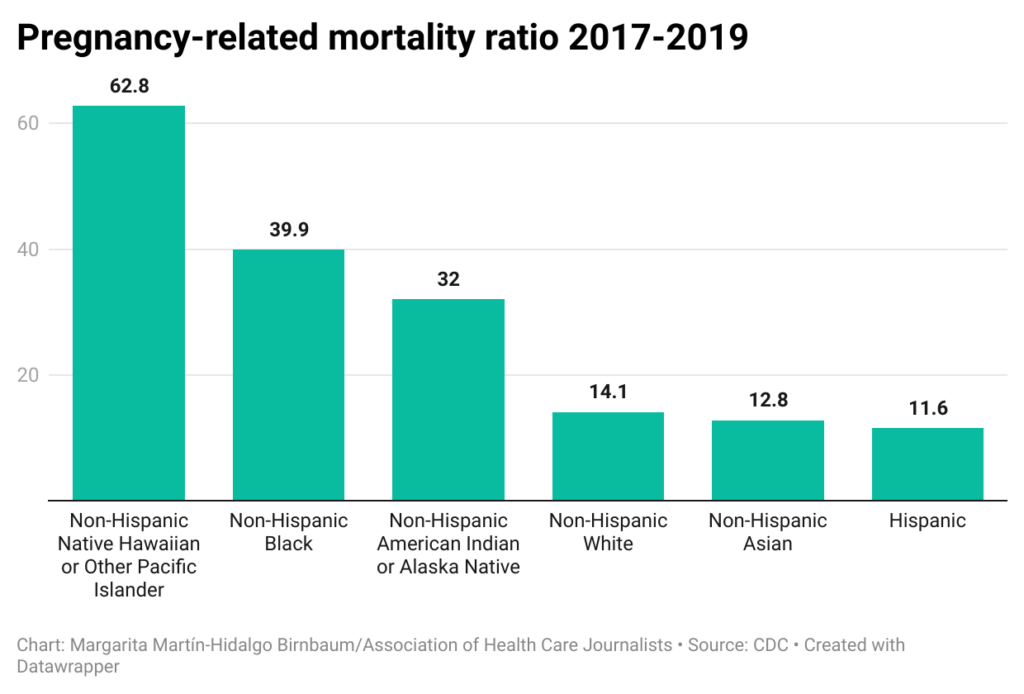

The maternal mortality rate in the U.S. has doubled in the last 20 years, a recent analysis found. What’s more, the study showed that Black, Native American and Alaska Native mothers are much more likely to die from pregnancy-related issues than their peers of other racial and ethnic groups.

While the population trends raise significant questions about access to obstetric and gynecological care available to U.S. mothers, the regional trends underscore just how common pregnancy-related deaths have become here and how widespread the problem is.

The disparities exposed in the analysis published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in July are critical to include in any article about maternal health care. Here are some of the key findings from the study that looked at maternal death rates from 1999 to 2019:

- The maternal death rate for Native American and Alaska Native women more than tripled from 1999 to 2019.

- The maternal mortality rate increased in all U.S. race and ethnic groups, but not equally in all of them.

- Black, Native American and Alaska Native mothers are much more likely to die in childbirth than peers from other racial and ethnic groups.

- The Midwest saw the most significant rate increase relative to other regions.

Writing about the maternal mortality crisis

As new reports increase awareness about maternal mortality in the U.S. and the factors driving it, we’re challenged with reporting on the most up-to-date and nuanced information while avoiding publishing the same story over and over again. That’s especially true when we have to address how insurance coverage, quality of care, shortcomings in medical practice and other factors drive disparities.

When writing about maternal health care in your community, consider researching trends and issues in other counties and states. Those can include:

- Maternal health education campaigns created by hospitals, governments, and nonprofits,

- Population disparities in causes of maternal deaths,

- The economic and emotional impact of maternal deaths on children and families,

- Local, state and federal funding for maternal health

- Efforts to improve tracking of maternal health measures.

Reaching out to colleagues who cover the health beat in different cities or regions is another way you can find new story ideas. They could be writing about things you haven’t thought of, help you identify credible sources in their communities, and share resources you weren’t aware of.

Among the news articles that ran immediately after the study’s release, AP reporter Laura Ungar’s story stands out because of the findings she chose to highlight, the sources she talked to and the issues addressed in the interviews.

Study co-author Allison S. Bryant, M.D., M.P.H., told Ungar that the findings are a “call to action” for physicians to understand the underlying causes of these troubling statistics. She added, “some of it is about health care and access to health care, but a lot of it is about structural racism and the policies and procedures and things that we have in place that may keep people from being healthy.”

Guardian reporter Michael Sainato covered a lot of ground in a recent story about the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act. A group of bills introduced in 2020, the proposed law mandates research to learn more about the maternal morbidity and mortality trends in Native American and Alaska Native women and supports studies looking at how housing and nutrition affects health.

It also allows the government to award grants to help mothers get treatment for postpartum depression and drug addiction, among other mental health and substance use disorders. The package was included in the Build Back Better Act in 2021. While it failed to pass by one vote, the bill was reintroduced in May 2023.

By reminding readers that U.S. Olympic track star Tori Bowie died in May during labor, and that Beyoncé and Serena Williams had their own harrowing experiences with pregnancies, Sainato underscores that the problem cuts across socioeconomic lines.

A higher level of educational attainment — and by extension, a higher income — may not protect Black women. In a 2020 analysis, researchers from The Commonwealth Fund found that college-educated Black mothers have a “60% greater risk for a maternal death than a white or Hispanic woman with less than a high school education.” The 2017 story of the death of a CDC epidemiologist, co-published by ProPublica and NPR, brought that point home.

“Nothing protects Black women from dying in pregnancy and childbirth,” reads the article’s headline. “Not education. Not income. Not even being an expert on racial disparities in health care.”