By Margarita Martín-Hidalgo Birnbaum and Joseph Burns

Epidemiologists, physicians, sociologists and health equity experts are increasingly shedding light on the relationship between quality of health and educational attainment, insurance coverage, access to safe home environments and other social factors. That means journalists are expected to give more context about health trends — even if the story is about the latest diabetes statistics in U.S. race, ethnic and Indigenous groups.

In this tip sheet, we share resources to help journalists give more nuance to current and future health trends in Native American and Alaska Native people. The Native American Journalists Association also offers relevant materials such as a style guide and link to a media archive. Below you’ll find information on tribal and federal public health agencies, names of academic centers and private research institutions, and Twitter accounts of reporters and media outlets.

-

Need social demographic data? Turn to tribal governments and U.S. Census Bureau. For example, you can find comprehensive population information about the Navajo Nation on this site. If information is not readily available on a tribe’s website, reach out to their communications representatives.

Media representatives and researchers at the U.S. Census Bureau are eager to share information. Lean on them to find and understand it. Also, the agency offers webinars and how-to videos to find statistics and hard numbers on income, housing, broadband access and more. And the data dissemination specialists are a great resource in part because they offer trainings. For more information on that program, check out this webpage.

-

For health data, reach out to tribal and federal health agencies. A 1996 federal law established Tribal Epidemiology Centers, more commonly known as TECs. There are 12 of them spread around the country; they help tribal health departments promote public health campaigns and track disease incidence and prevalence.

Keep in mind though, that a significant challenge in covering Native American and Alaska Native health is that existing data may not be accurate, up-to-date or comprehensive. In a recent report, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) said that not all of the TECs can access non-public data from the federal U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) or from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Some of the TECs could not get CDC data on positive COVID-19 tests or IHS data on patient diagnosis codes. It said that such vital data were not available to the tribal centers because:

-

There were few policies affirming the authority of the TECs to access HHS data.

-

There was little guidance on how TECs could request the statistics.

-

There were few procedures on how HHS and CDC should respond to such requests.

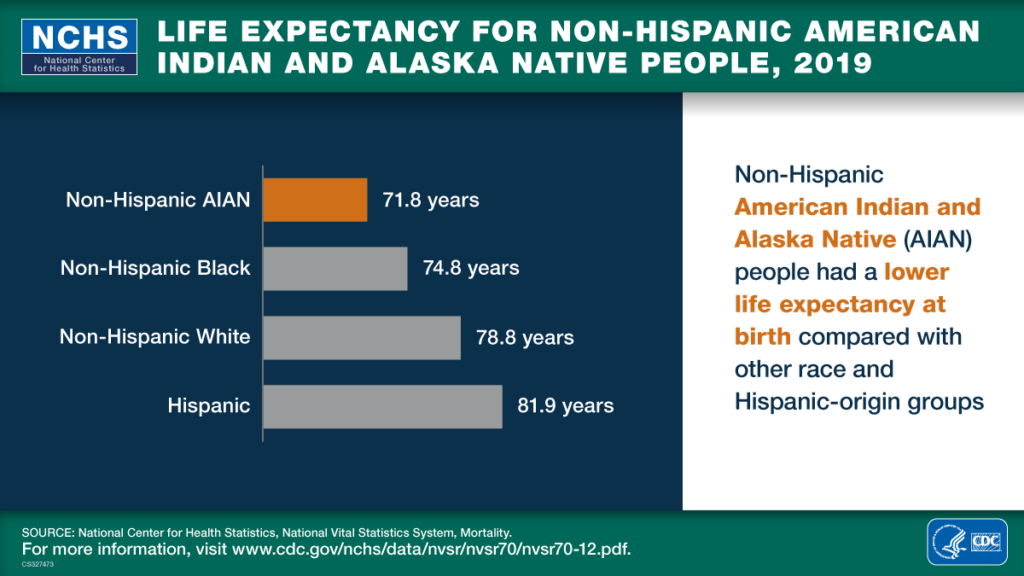

Although the Indian Health Service is the government agency dedicated to providing health care to the 574 federally recognized tribes, other federal entities also serve Native American and Alaska Native adults and minors. They include Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and the Veteran’s Administration. The National Center for Health Statistics and the CDC may have some of the most current reports on Native American and Alaska Native health trends.

Remember that if there’s not enough data, that’s a story. If the data is unreliable, that’s a story too.

-

When the story warrants it, interview sources who study Native American and Alaska Native history, customs and culture. Historians, food studies experts, identity researchers, economists, public policy experts and other scholars complement the nuances you’ll get from physicians, epidemiologists, psychologists and other health care and medical services providers. In “Rezilience: Surviving Manifest Destiny,” a series about Native American and Alaska Native health, journalist Céline Gounder, M.D., S.c.M., F.I.D.S.A., interviews an agricultural expert and a Native American studies professor to explain how forced relocation, attacks on the food supply by U.S. government forces and policies that limited access to fresh foods have played a role in the current worrisome health trends in Native American and Alaska Native people.

Find and vet experts looking at their online profiles. Take the time to find studies on PubMed that may help you narrow down who your best sources may be. If you need help setting up interviews, ask communications staff at universities, community colleges and think tanks to help you find them.

-

Don’t overlook reports and studies that look at the relationship between health equity and public infrastructure, broadband access, zoning laws, environmental pollution and other social determinants of health. That data is particularly useful in stories that look at trends over long periods of time. The Commonwealth Fund and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation are among policy research institutions that look at these concerns. Some universities and colleges have entities dedicated to research about issues affecting Native American and Alaska people, including the American Indian Policy Institute at Arizona State University, the American Indian Center at the University of North Carolina, and the Native American Center for Health Professions at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

-

Use Twitter, Facebook and other platforms to follow media outlets, reporters, and podcasts. See the list below for Twitter accounts of some of those sources.

-

Navajo Times: @navajotimes

-

Native News Online: @nativenews_net

-

Indian Country Today: @IndianCountry

-

Native Public Media: @NativePublicMed

-

Bryant Furlow, reporter New Mexico in Depth, ProPublica Local Reporting Network and The Lancet: @bryantfurlow

-

Felicia Fonseca, reporter at the Associated Press: @fonsecaap

-

Savannah Maher, reporter at Marketplace: @savannah_maher

-

National Congress of American Indians: @ncaii944

-

American Indian Policy Institute, ASU: @aipinstitute