Lung cancer is by far the leading cause of cancer death among both men and women. It accounts for almost 25% of all cancer deaths. The American Cancer Society estimated that in 2021, approximately 235,760 new cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed and 131,880 people will succumb to the disease.

Lung cancer screening provides an opportunity to detect lung cancer at an early stage when surgical intervention can be curative. Screening guidelines strongly influence who gets referred for screening and what tests insurance providers will cover for whom. But the current screening guidelines may overlook vulnerable populations with disproportionate lung cancer burden and inadvertently lead to delayed diagnoses and poorer outcomes. Research shows that Black people are at a higher risk of lung cancer than the general population, even if they smoke less over time.

Few people understand how screening guidelines are developed and their impact on personal health. Health journalists can use research about lung cancer screening disparities to shed light on the process and help people advocate for the screenings they deserve.

Racial and ethnic lung screening disparities

The lung cancer screening guidelines are based on clinical trials conducted with subjects who are predominantly white Europeans. The 2011 National Lung Cancer Screening trial studied more than 53,000 current or former heavy smokers to determine the cost and effectiveness of a form of screening called low-dose computed tomography (LDCT). Fewer than 5% of participants were Black.

A European trial on the same topic, the NELSON lung cancer study, also studied LDCT screening with 7,557 participants. The researchers made no mention of people of African ancestry. Including more people of color in clinical trials could have a significant impact on screening guidelines.

Based on these studies, the 2013 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines recommend screenings for smokers age 55 to 80 who have a 30 pack-year (years smoked multiplied by the number of packs smoked per day) history and who still smoke or have quit within 15 years.

A Vanderbilt University study published June 27, 2019, in JAMA Oncology found that the guidelines were perhaps too conservative for Black Americans because they leave out many people at high risk for the disease. Among smokers diagnosed with lung cancer, researchers found that 68% of Black smokers were ineligible for screening at the time of their diagnosis compared with 44% of white smokers. Among patients diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer, the median age for diagnosis for whites was 63 compared to 59 for African Americans.

The USPSTF cited the study as a factor in lowering their recommended screening age for lung cancer from 55 to 50 and reducing the number of pack years from 30 to 20. Lowering the minimum age and pack years will greatly expand eligibility to an additional seven million Americans.

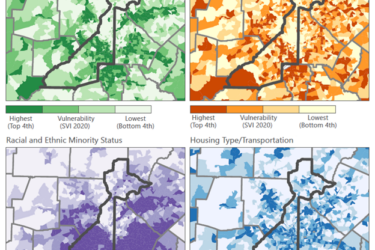

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Lung Cancer Screening Eligibility published in the September 21, 2021, issue of RSNA Radiology evaluated the impact of revised USPSTF guidelines on racial and ethnic disparities in LCS eligibility. Data from the 2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey shows that racial and ethnic minority groups remain less likely to be eligible for lung cancer screening because the new USPSTF lung cancer screening guidelines may still exclude large numbers of high-risk Black smokers.

A higher proportion of Black adults within this expanded eligible group will be uninsured. As a result, even these new guidelines could have the unintended consequence of worsening instead of improving screening for Black people, according to Lung Cancer Screening Eligibility and Screening Patterns Among Black and White Adults in the United States published in JAMA Network Open October 2021.

There is some good news on the lung cancer front, however. The number of new cases continues to decrease, partly because people are quitting smoking. Advances in early detection and treatment have also resulted in a decline in the number of lung cancer deaths.

Resources for reporters