About this time every year, the story of Dan Jennings, a man I got to know fairly well, always seems to come to mind. It was Sept. 14, 1999, when his odyssey as a patient zero of medical errors began, and became a wake-up call for me, a journalist, who realized how easy it is for lapses in simple safety protocols to ruin lives.

Jennings was 46, an educator for a San Diego company that sold devices to treat patients with sleep apnea. He traveled around the country teaching doctors about diagnosing and treating the disorder and demonstrating the correct use of continuous positive airway pressure devices, or C-PAPs.

But as he got off a plane one day after yet another educational trip, he felt severe pain in his stomach. A few days later, his doctor admitted him to a large San Diego hospital for elective surgery. He needed a repair of a common bowel problem. The surgeon, Dr. Fred Hammill, told him not to worry. He performed these procedures all the time.

That day of the week, Tuesday, was special because it was what Hammill called his “marathon” day, when he would operate 14 hours straight through, Jennings said. Jennings would be his last patient.

After a few days, Jennings was discharged home. Piece of cake.

But that pain he was promised would go away just wouldn’t. He repeatedly complained, calling Hammill and the hospital. What’s more, he couldn’t bend his body without feeling excruciating pain. And it just got worse. Two weeks went by. He was told not to worry. He would heal. The pain would go away as he recovered.

But it didn’t.

Desperate, he persuaded a friend to drive him to the hospital. The friend carried him down the stairs from his second-floor apartment to his station wagon on a board, so he could lie flat and wouldn’t have to sit or bend. The hospital brought him in for X-rays to see what might be causing the pain.

“Please get off the table, because there’s some sort of object on it,” the technician told Jennings after the first set of images. But there it was again. “Put on a different gown,” the tech said. Now move to a different X-ray machine.

By the third series, the technician was frantically calling Jennings’ surgeon.

A fuzzy light gray image about 14 inches by 2 inches appeared on the screen. A metal retractor was still inside his abdominal cavity. Jennings would have to undergo another surgery to remove it.

But damage was already done. During removal, surgeons saw that necrotizing fasciitis infection, which can occur when tissue reacts to metal, had plowed through Jennings’ intestines.

He would undergo multiple subsequent surgeries and try to control pain with drugs for the rest of his life. He couldn’t return to work. A lawsuit was filed, and Jennings got about $250,000 in pain and suffering, the max due to California’s MICRA law. Hammill, the surgeon, stopped practicing for awhile, apparently after another round of litigation on a different case.

Around this time every year I used to call Jennings to find out how he was doing since my first story about him ran in the San Diego Union back in 2001. Often, he would sound so depressed, still in pain, unable to work or move around very well, and every year his bitterness seemed to grow. He would always thank me for writing about his case, to draw attention to the suffering one medical mistake can cause. His story and picture, retractor and all, even made the New York Times.

We call these types of surgical errors by many names now. Retained foreign object seemed too clinical. It tended to de-emphasize the severity. So organizations began calling them forgotten surgical bodies or items, to convey the idea that they didn’t just magically appear from a foreign agent. They were inserted and were supposed to be removed but teams of nurses and doctors forgot them.

Often when the tools are made of cloth, they are given fancy names like gossypibomas, textilomas or cottonoids. Do patients understand what those are? Imagine being told, “Oh I’m sorry, Ms. Clark, but we see you have a gossypiboma. Don’t ask. We’ll need you to come back for another surgery. How’s tomorrow?”

Sophisticated tagging and cataloging strategies, even a door hanging shoe container, have tried to keep track of every item used during surgery to make sure that whatever tool goes in to a human cavity comes out and stays out. But the problem has not gone away. Time outs, double counting, triple counting have helped but have not resolved the issue.

One surgeon has made this a cause and I interviewed her years ago. Dr. Verna Gibbs, professor of surgery at the University of California San Francisco, started the campaign, “NoThing Left Behind,” a project to eliminate retained surgical items everywhere.

Regulatory statements of deficiencies filed against surgery centers or hospitals have documented long lists of forgotten bodies with a mind-boggling variety:

Nuts, bolts, screws, gauze, clamps, sponges, electrodes, drains, drill bits, guide wires, towels, tubing, tissue specimens, broken pieces of a scalpel blade, cautery fragments, plastic items, wound protectors, sensors, surgical thread, catheters — even a denture and jewelry — have been discovered, often after patients complained of pain or fatigue that turned out to be caused by that – “Oops. Where did that tool go?” event.

In one case documented in the Journal of Emergency Medicine in April, a surgical thread was found in an 84-year-old woman who had undergone a hysterectomy 21 years previously.

A PubMed search turned up a variety of case studies and reports about the issue, including one suggesting that the incidence of retained surgical bodies remains “between .3 to 1.0 per 1,000 abdominal operations.” Apparently, the abdomen is a hiding place of choice for many of these materials.

I wrote up my story about Dan Jennings as a column about 10 years ago when I worked for HealthLeaders Media. Back then, the organization encouraged comments on content, and a few weekes later when I went back to the site to grab the link, I saw this post:

Sherry Chaffin (9/19/2010 at 8:41 PM)

This article written my Cheryl Clark 12/2/2009 is about my cousin, Dan Jennings. I just wanted to add for anyone that may be interested that Daniel passed away on 9/10/2010 in his home in Fredricksburg, TX after 10 years of pain & suffering & depression from this horrible mistake. If you can let Cheryl Clark know, it would be greatly appreciated, as we appreciate her writing this article. Thank You, Sherry Chaffin

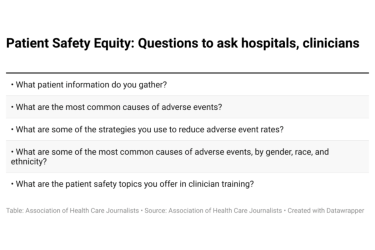

I’m excited to be writing about patient safety again as the Association of Health Care Journalists’ core topic leader on patient safety. It is still a huge and important issue. It kills people. And I hate that, especially this time of the year.