On its surface, the central argument in Jonathan Metzl’s most recent book is a surprising one and a departure from his previous books and public statements. One of those books, “Dying of Whiteness,” made a strong case for why gun violence needs to be treated as a public health crisis.

In “What We’ve Become: Living and Dying in a Country of Arms,” Metzl doesn’t say the public health approach to gun violence is wrong. Rather, he said it can’t work as the sole solution.

A “prevention-based model alone cannot adequately conceptualize or meaningfully address the larger issues posed by guns,” he writes.

The “public health model” for reporting on firearm violence began to gain traction in the early 1990s as researchers and policymakers sought to find ways beyond “gun control” to reduce the number of gun deaths each year in the U.S. One year ago, the Surgeon General issued an advisory, declaring firearm violence a public health crisis — rescinded by the current administration.

Metzl, who talked about his book at HJ25 in Los Angeles, said the role of politics, identity, racism and power need to be a part of a more effective prevention model.

He never said stronger gun laws and public health policy doesn’t work. But he does make a strong case for why the messaging around those solutions isn’t working and is failing to reach gun owners.

Metzl also offers solutions to broaden the public health prevention framework to be more effective at preventing gun violence and regulating firearm ownership.

Public carry

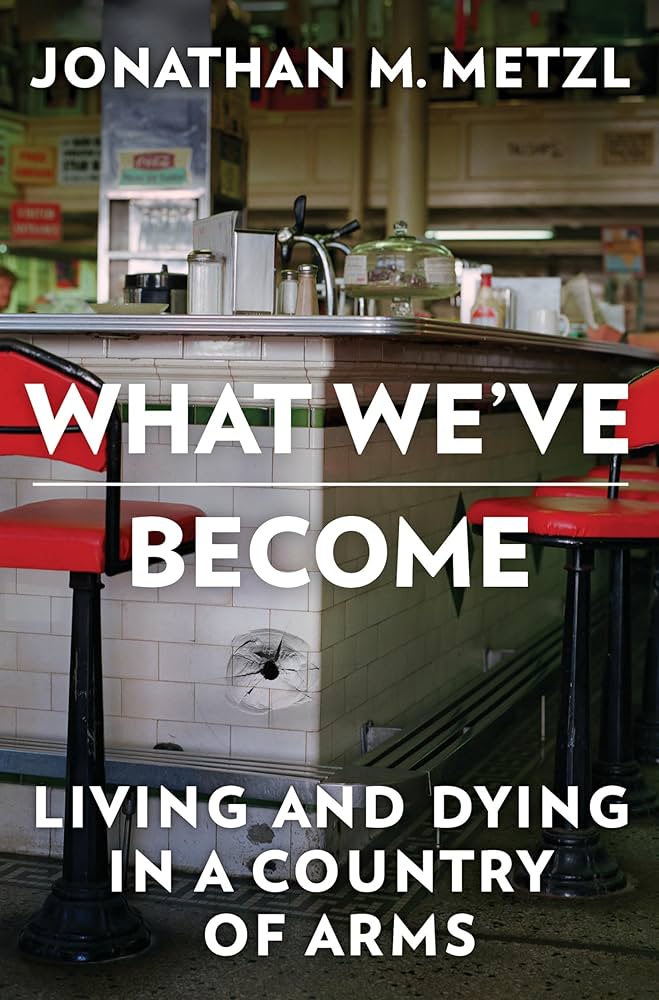

The thru-line of Metzl’s book is a mass shooting at a Waffle House outside of Nashville in 2018. Travis Reinking, a white man from Illinois, fatally shot four young people of color and injured four others with an assault-style rifle inside the restaurant.

While there were many contributing factors to that deadly moment, Metzl said Reinking’s right to carry guns in red-state America was a major part of why he carried out the shooting.

One of the main issues Metzl focuses on is unregulated public carry of guns, which he said should not be seen as inevitable.

“Changing course also means coming up with better strategies to address the issue of public carry and building consensus around the public sphere, that area of social life where people can come together to freely interact, exchange commerce and ideas, discuss and identify societal problems, and devise shared solutions,” he writes.

But public carry threatens that, especially in states that don’t regulate guns in public spaces.

“And the traditional public health responses, like point-of-sale background checks, red flag laws, and assault weapons bans, provide insufficient counter to the decisions of pro-gun courts and judges in a world in which guns increasingly become inevitable actors in American daily life.”

In that vein, gun owners need to be a part of the solution and researchers need to do more to understand their motivations, especially related to their perceptions of public safety.

Guns aren’t cigarettes or cars

Public health models played a key role in reducing deaths and injuries from public health threats like automobiles, cigarettes and alcohol. And as the idea that gun violence is a public health issue became more mainstream, researchers thought the same models that reduced deaths and injuries from cars and cigarettes could be applied to guns.

“Guns — like cars, stiff drinks, and cigarettes — caused corporate-sponsored injuries and deaths,” Metzl wrote. “Public health scholars could show that gun deaths were ‘preventable’ … Untoward effects could be prevented from occurring in the first place by ‘targeting policies and interventions at the known risk indications for the problem, quickly identifying and responding to problems if they do occur, and minimizing the long-term effects of the problem.’”

But that didn’t work, Metzl argues. Guns are a different beast from cigarettes, cars or any other dangerous products under public health’s purview. That’s largely thanks to the efforts of the NRA.

The organization was “not just selling a product; it was building a sphere of influence” and creating a strong identity, Metzl said.

Expand the public health framework

Metzl lays out several solutions in his book, but one of the main arguments he makes is expanding the public health framework. That means researchers need to understand and listen to gun owners.

For example, Metzl said, they should look into gun culture, their perceptions of safety, how they view responsible gun ownership and the social, cultural and political landscapes surrounding guns and gun laws.

“Gun ownership is far from monolithic: different groups of gun owners increasingly carry guns and imagine personal and public safety in divergent ways,” Metzl writes.

He also points out how health-based research has struggled to engage with Southern, white, working-class populations when it comes to changing individual behaviors. They’re more likely to buy into an anti-government and anti-establishment narrative that stokes economic and racial grievances — a narrative pushed by the NRA, Metzl writes.

“Research with conservative white gun owners must keep those tensions in mind,” he writes.

Another solution he offers is investing in structural solutions, such as creating safer and more cohesive neighborhoods. Researchers have found a strong link between investing in a community’s infrastructure and reducing violent crime.

Metzl calls this a “structural competency approach” to gun violence prevention and it takes on the core assumption of the argument for open carry, (that public spaces should be safe for everyone) and intervenes upstream to foster public safety.

“Few of these interventions involve trying to mandate individual-level behaviors,” Metzl writes, “but instead aim to build structures that engage broader categories of shareholders and constituents to build what political theorists call ‘strategic influence’ by creating long-term sustainable relationships that fulfill practical benefits to citizens.”

He also points out that closer attention to economic realities and financial structures would counter the criticism that public health fails to factor in economic factors.

By tying economic improvements to gun safety in rural communities, that counters “rural resentment” feelings and focuses on improving rural life.

Metzl concludes that we need a unified narrative that focuses on values rather than regulations and is “proactive rather than reactive.”

“We need to do a far better job of defining and promoting our vision of public engagement by highlighting the way in which effective gun laws enhance the rewards and satisfaction of living in peace with one’s neighbors and male public spaces safer for children,” Metzl writes.