Michael Hawthorne, a Pulitzer-finalist investigative reporter who focuses on the environment and public health for the Chicago Tribune, has been reporting on PFAS for more than 20 years. He was one of the first reporters outside of West Virginia to write about PFAS, also known as ‘forever chemicals.’ And he won the Society of Environmental Journalists (SEJ) Outstanding Beat Reporting in a large market for his reporting on PFAS.

What are PFAS?

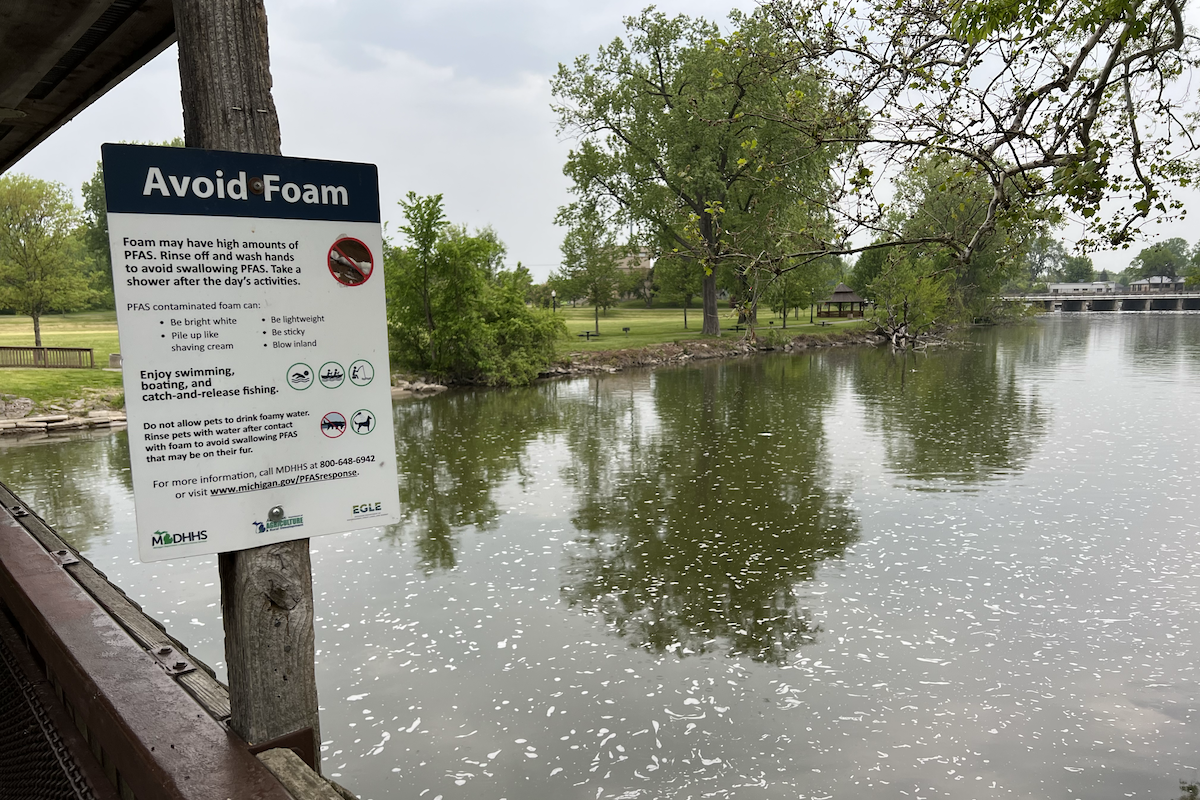

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic chemicals that do not fully break down in the environment or human body. Their chemical properties allow them to reduce friction and resist oil and water and, as a result, they have been widely used in industry and consumer products for decades.

These commonly found chemicals are used in industrial processes, firefighting foams and even nonstick cookware. PFAS are also used as protectants for paper packaging products, carpets, and textiles that enhance water, grease and soil repellency.

Although researchers are still studying the full impact of PFAS on public and environmental health, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry shows evidence that there are negative health outcomes associated with exposure to PFAS chemicals.

While working for the Columbus Dispatch in Ohio, Hawthorne reported on a coal-fired power plant that produced blue clouds of sulfuric acid mist that would descend on the nearby town. He worked with a geologist to test the soil and she said, “You think this is a story? I’ll tell you a story,” and proceeded to tell him about PFAS chemicals and Washington Works, which was Dupont’s main teflon producing plant. That is what led Hawthorne to the proverbial peeling back the layers of the onion and reporting on PFAS chemicals.

In this “How I Did It,” Hawthorne shared his approach to reporting on PFAS chemicals and where to source data for this elusive, unregulated topic.

The following conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

How did you find sources to interview and reliable data? What were the most valuable sources, and why?

I would say the No. 1 source is the state EPA drinking water testing data. You can request the data in a spreadsheet, and then figure out how many people are potentially affected.

The Safe Drinking Water Information System (SDWIS) allows you to look up individual water districts in a state and see how many people are served by that water district. You can mesh that data with the water testing data to get an idea of how many people are being exposed.

If you look at the state of Illinois, the state EPA gave what I thought was a misleading report by saying how many systems PFAS chemicals were found in, and it was a relatively small number compared to the total number of water systems in the state. But then, when you look at the number of people served, it’s a majority of the population in the state. This was another way that the state EPA minimized the potential risk to its citizens that it’s there to protect.

ECHO wasn’t the source for the regulatory documents, there are some documents in the federal regulatory docket about PFAS chemicals. The EPA will occasionally post these documents on regulations.gov where you can find the Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. This is basically a signal to lawyers who are part of the regulatory community, that says the EPA is thinking about doing something and here’s who would be affected. In most cases, we don’t know who is discharging PFAS pollution because the chemicals aren’t regulated. But there are standardized industry codes called NAICS. Based on U.S. EPA research, industries with certain NAICS codes are likely the sources of this pollution.

So then, you go back into the echo database and you search under those codes and it will spit up every factory and everybody that has a permit, air or water permit in the country, and there’s your list of known or suspected PFAS polluters.

This data is pretty readily available and you can figure out how many companies in your community are potentially putting PFAS chemicals into the sewers. Then, you can start asking what is being done to limit that pollution and figure out if PFAS chemicals are there. In many cases, the answer is probably going to be, we don’t know. That is going to change. Hopefully, pretty soon. The EPA put out a memo a couple of years ago saying that they are going to start requiring regular testing for these chemicals when we renew your water pollution permit.

What was the most challenging part of reporting on PFAS?

This stuff is complex, and your challenge as an environmental health reporter is to essentially be a translator. You want to use the technical language, in some cases, to signal to the people who are doing the work that you know what you are talking about, but also you want to make it understandable. When you get all this data, you want to ask yourself, how do I make sense of this and how do I grab people’s attention, and I too struggle with that.

I eventually just laid it out and said, these PFAS chemicals are here, this is what they do. Here is a brief explainer of what they are and here is where it is at. Keep it simple, which is tough to do when you are dealing with anything public health or health in general. These are complex subjects, and with the environment, you are dealing with complex chemistry.

What should health care reporters who are less familiar with PFAS know? Were there findings that stood out to you?

The National Academies of Science is urging doctors to test their patients’ blood for these chemicals. That’s a starting point, and from there, you can ask if any physicians are testing for PFAS chemicals in your community. There are a lot of scientists and public health experts out there now who can talk about this.

Reporters should also try to figure out if their state tested drinking water supplies for these PFAS chemicals. And if so, what are the results and how do they compare to the EPA’s proposed legal limits. If they are over the limits, then you can ask your mayor and sewage treatment managers what they are going to do about it.

The Biden administration has put out a lot of funding to address the PFAS chemical problem, so I would encourage reporters to see if any of that money is going to their community. And if so, how is it being spent?

What was it like making the PFAS tool for the public to use? What is your advice to health care reporters who want to do something similar?

Keep it simple. What I did was just take the raw data and simplify it. The tool asks you to type in your water system, and after you enter that, a little box comes up that says which PFAS chemicals were detected. If the amount of PFAS that was detected exceeded Illinois EPA health guidelines, we put them in bold with an asterisk explaining that it exceeded the limit.

We wanted to simplify the measurement nomenclature so that the average person could understand or find it relevant. We wanted to communicate, “A” is it there? And “B,” does it exceed the health guideline or legal limit?

How does reporting on PFAS chemicals vary depending on location? What tips do you have for reporters looking at forever chemicals in other states?

Some states don’t test for PFAS chemicals at all, so I would go back to some of the strategies mentioned earlier. You can at least find the potential industries using the ECHO database, and that can be a starting point for asking questions. I would also recommend seeing what kind of PFAS investigation has already been done by other reporters, nonprofit groups or the state.

There are some communities where this has become a really big issue, like Dalton, Ga., which is home to the American carpet industry. Some of these PFAS chemicals were used to stain proof carpets for many years. In Georgia, local papers have been writing about the PFAS chemicals for a long time.

When I was using the ECHO database to find potential PFAS polluters, I found a lot of metal plating shops, which there are a lot of in the Chicago area. These often small shops don’t stand out, and they are often in nondescript buildings without smokestacks, so they don’t look like an obvious polluter.

Do you plan on pursuing more stories related to this topic?

There was a big legal settlement recently where all of these cases from communities across the country sued 3M and Dupont, and some of the other PFAS manufacturers. In the settlement, the companies agreed to spend many billions of dollars on clean water projects in the communities that sued. Anyone who is writing about this should look into if their community is in line to get any of this money and what they have to do to clean up this water supply.

I will continue looking into sludge in the Chicago area. There is a scientific advisory board to the EPA that’s looking into what the EPA should do about this. There is a lot of lobbying going to exempt entities from superfund regulation or liability.

These chemicals are so ubiquitous and have been used in so many processes and consumer products, that it’s hard to avoid them. I did an explainer on how you can reduce your exposure to chemicals. I am interested in PFAS chemicals because there is a lot going on and a lot to be discussed about if anything is going to happen at the federal level to protect Americans.