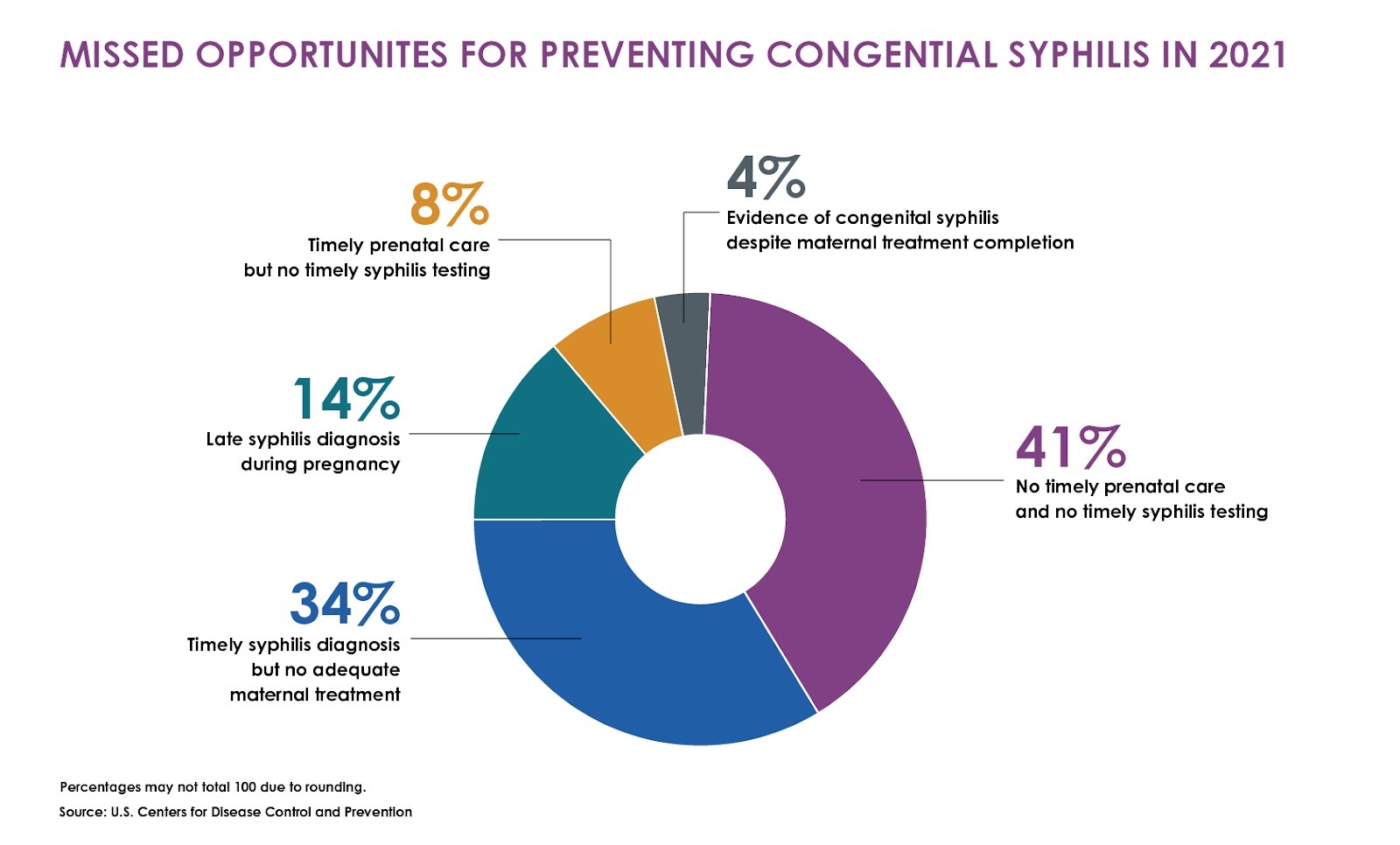

The U.S. is among many countries grappling with a syphilis outbreak. Increases in the number and rates of the disease have been notable over the last decade, but rising cases in newborns have renewed attention to the crisis. As clinicians race to stem the spread, population trends suggest that many Americans of color living with the disease aren’t getting treated for it.

While the number of reported syphilis cases is a lot lower than those of chlamydia and gonorrhea, two other common sexually transmitted diseases, untreated syphilis may lead to meningitis, neurological problems, hearing loss, and in rare cases, death. Pregnant women may have a higher likelihood of miscarriages and preterm births. Infants born with the infection have a higher risk of developmental problems and mortality.

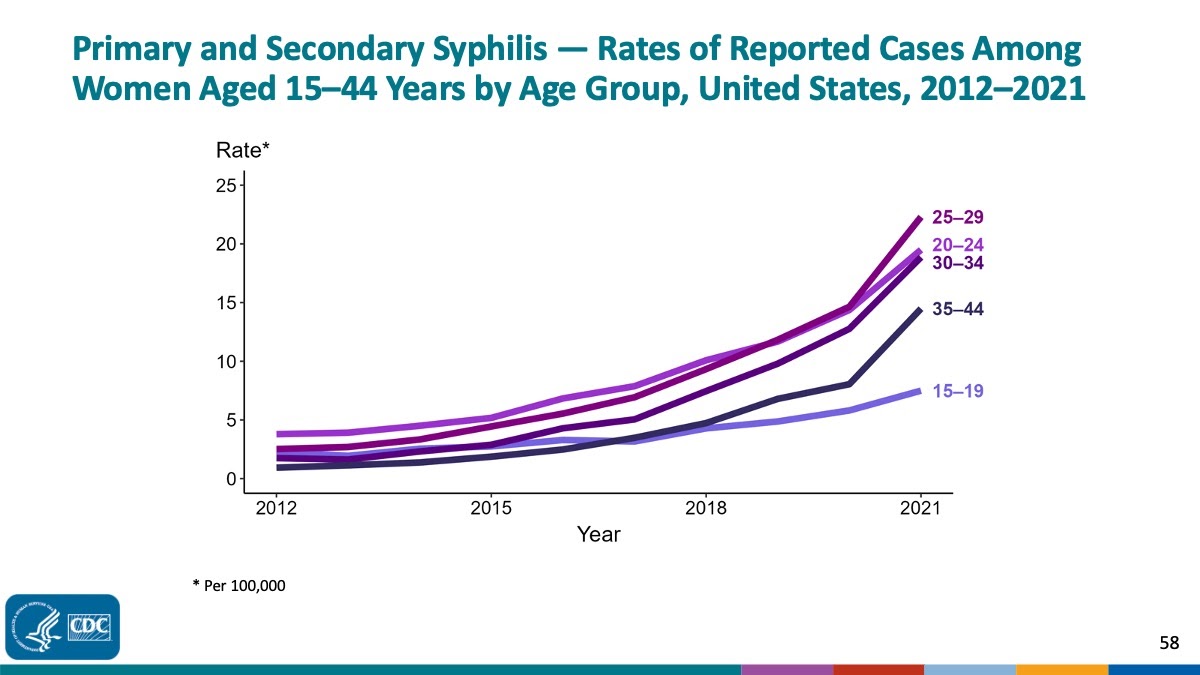

Reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis surged by 38% between 2019 and 2021, according to CDC data. Although coronavirus restrictions limited access to detection services and treatment, the federal agency has said that “a crumbling public health infrastructure, reductions in STD screening, treatment, prevention, and partner services contributed to STD increases for many years even before the pandemic.”

As long-term implications of the contagion are revealed, reporters writing about it should lean on pre-pandemic studies and data to bring context to the trends in racial and ethnic groups.

The population disparities raise questions about the effects the crisis may have on the health outcomes of people of color, particularly Black, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander and Native American and Alaska Native people. CDC data shows that overall syphilis rates are significantly higher among people from those racial and ethnic groups relative to their peers from other demographic populations.

Factors influencing trends

In studies and reports published over the past decade, researchers have addressed social and behavioral reasons that may explain why syphilis has become an epidemic 20 years after numbers had come to a trickle relative to what they had been. On their list of factors that may be driving the contagion:

- Lack of insurance coverage.

- Racist views clinicians hold about people of color.

- Unstable living circumstances.

- Sexual practices.

- Drug use.

“The issues are really, really quite complicated about why this is happening — and why certain populations are impacted more than others,” said Helena King, M.D., an associate professor in the division of infectious diseases and geographic medicine at the UT Southwestern in Dallas.

This summer, King and other clinicians around the country learned their efforts to tackle infections would get a lot harder. Pfizer, the manufacturer of Bicillin, the preferred antibiotic to cure syphilis, announced that increased demand and syphilis infections had created a shortage of the medication that would stretch into 2024. Although doxycycline will do in a pinch, King said Bicillin is more effective because it is administered in two intramuscular injections and the course is shorter.

But there are other, less obvious factors that are making the job harder for clinicians on the front lines of this crisis.

For example, King argued that a deeply-rooted reluctance to talk about sex and long-held stigmas about STIs in this country are two major obstacles to curbing the spread. Mistrust in health care providers and the medical system at large is also keeping people from getting routine medical care that could catch the infection in time and get people the treatment they need, King said.

While men who have sex with men have represented the vast majority of people with syphilis, reported infections in cisgender women and men have been rising. An infectious disease expert interviewed for this article in STAT told reporters Bree Iskandar and Abdullahi Tsanni that trends we’re seeing may be the result of activity between “sexual networks or social networks that didn’t used to mix.”

The authors of this 2019 review about the trends over the last decade addressed the influence technology may have on them. Citing research about online dating apps, they argued that “the increasing popularity of dating apps, especially among the younger MSM population, has created a virtual landscape of social-sexual networks that are not only more complex and challenging to identify, but potentially increase risky sexual behavior.”

Prevention efforts

One of the things that confounds King is why available public messages about the STI transmission and prevention don’t seem to be sinking in the way they should. In her practice, many of the patients she sees — the vast majority of whom are Black and Hispanic — don’t realize that they can have an STI and not know it because they can be asymptomatic.

Among the consequences of syphilis that King thinks journalists should address more is the link to HIV. She explained that people who acquire the bacterial sexually transmitted disease (as well as others) have a higher likelihood of being exposed to HIV, partially because inflammation in the infection site breaks down the mucosal barrier that protects people from the virus that causes AIDS.

But she’s noticed that many patients who know they should get tested for STIs “don’t really have that understanding that they might want to consider HIV preventive care.”

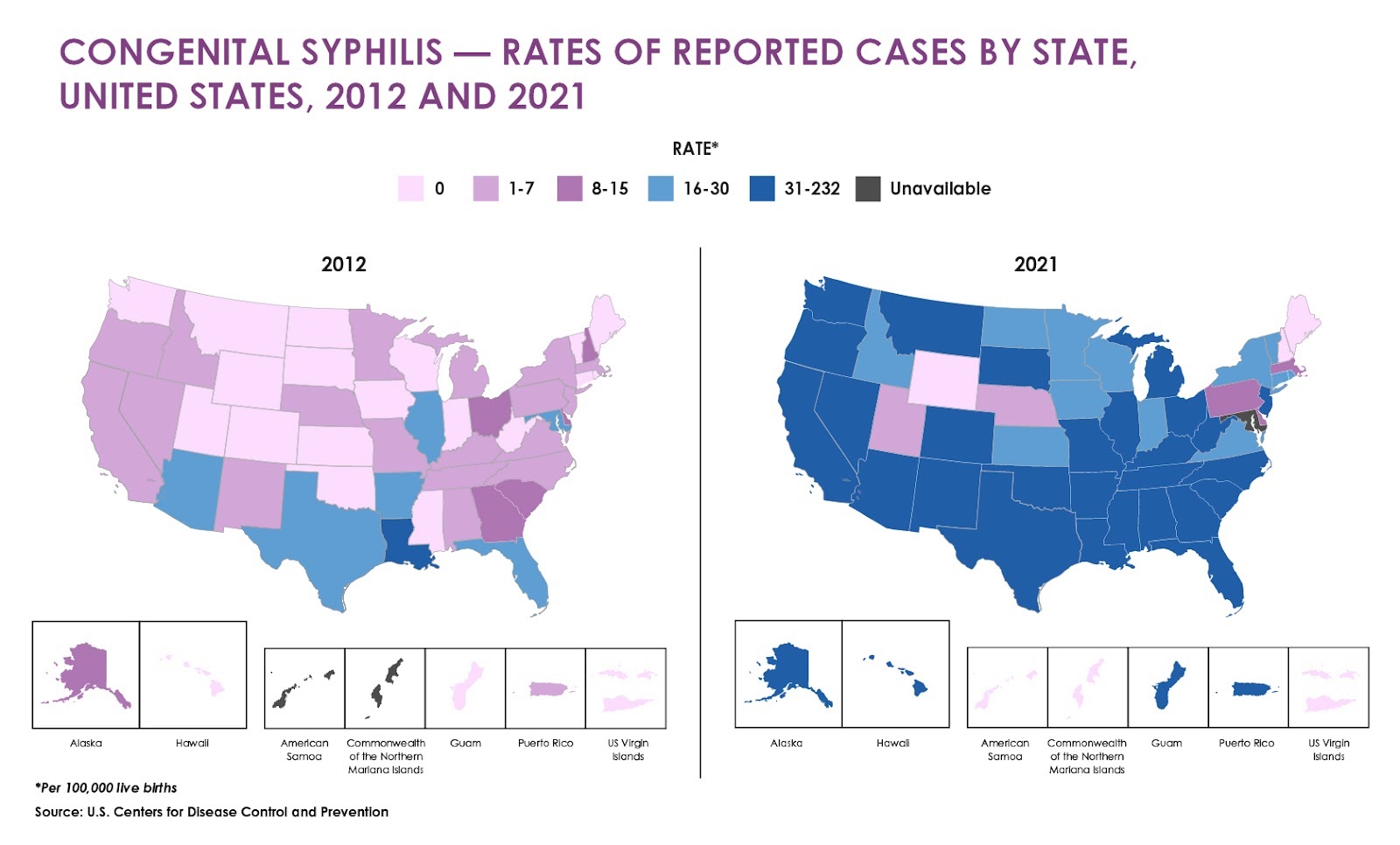

People’s awareness of protective options has everything to do with prevention campaigns. To tell that part of the story, start by looking at geographic data. The state-by-state rates suggest that the reasons for those disparities have to do with the availability of testing and treatment, the quality of health care services people have access to, and public education campaigns. This is also closely related to government funding.

To get a sense of how much effort health officials and legislators are really making to reduce the number of cases in their communities, look at the state budgets for the past several years. Those reports may show how much of the money allocated to curb syphilis transmission comes from state coffers and how much of it comes from grants from the CDC and other federal agencies. Moreover, the funding will shed light on why trends have improved, worsened or remained the same.