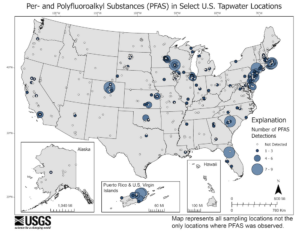

At least 45% of the nation’s tap water is contaminated with one or more “forever chemicals,” according to a recent U.S. Geological Survey study. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as “PFAS,” are commonly found in cleaning products, nonstick cookware, water-resistant fabrics and more.

The finding creates a challenge for water agencies across the country as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency moves to regulate the amount of PFAS allowed in drinking water by the end of the year.

These man-made forever chemicals used in household and industrial products do not break down in the body or in the environment. Once they enter the human body, the adverse health effects can include low birth weight, asthma, cancer and impaired liver and kidney function. A 2015 CDC study found at least 97% of Americans have PFAS in their blood. More than 9,000 PFAS have been identified so far, according to the CDC.

In March, the EPA proposed a rule regulating six PFAS in drinking water for the first time. The EPA is expected to finalize the proposed regulation at the end of 2023 under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Several states have already taken action to cut down on the use of PFAS, and some have started to spotlight widespread exposure to forever chemicals through drinking water.

The EPA’s proposal sets the maximum amount allowed in drinking water for these six PFAS:

- Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

- Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS)

- Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA)

- Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA, commonly known as GenX Chemicals)

- Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS)

- Perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS)

“Communities across this country have suffered far too long from the ever-present threat of PFAS pollution,” said EPA Administrator Michael Regan in a March press release announcing the proposed rule. “This action has the potential to prevent tens of thousands of PFAS-related illnesses and marks a major step toward safeguarding all our communities from these dangerous contaminants.”

The federal government has taken several actions over the last few years related to PFAS leading up to the latest proposal:

- 2016: EPA issues a health advisory on PFOA and PFOA, which sets a “safe level” of the chemicals in drinking water at 70 parts per trillion.

- 2019: EPA issues a formal PFAS Action Plan.

- 2020: EPA updates the plan and outlines actions that were taken to mitigate the chemicals.

- 2022: EPA issues a proposal to designate two of the most-used PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances to trigger reporting of the release of these chemicals.

Under the latest proposal, water systems would be required to monitor and post PFAS levels for the public to see and to decrease levels below the federal standard.

At the state level, various legislatures have been working on issues related to PFAS in recent years. According to the National Council on State Legislatures, state lawmakers considered more than 200 PFAS-related bills last year. Of those, 18 states approved nearly 50 bills regarding PFAS usage and remediation.

Reporting on PFAS and the slew of proposed and approved regulations can be complex. For journalists, understanding the toxicity and the long-range impacts is critical. Finding those who are impacted — or could be — is also important for coverage. Solutions are also part of covering this topic long term. Companies are creating early systems to destroy the PFAS chemicals in water, but the technology is expensive and not widespread yet.

Story ideas

- What will your state do?

- How prepared are the state and local water systems?

- What is the PFAS exposure rate in your area, and can you pinpoint a specific census tract with the worst exposure? Who lives there?

- What can residents do about PFAS now? Should they use water filters, buy bottled water, or install special water systems?

- Is there a way to show what the exposure does to people? Can you find patients dealing with the effects of long-term exposure? Maybe someone who worked closely with such chemicals?

- What is the state of PFAS testing for people? Testing is available but it’s not easy to obtain, and it’s not part of any routine testing for kids, pregnant people or adults. Experts say they would like to see this but is it likely given the cost?

Recent reporting

- Los Angeles Times – Risk of tap water exposure to toxic PFAS chemicals higher in Southern California

- Kansas City Star – Tap water in Kansas was tested for ‘forever chemicals.’ Here’s where they were found

- Michigan Live – Forever no more: New tech ‘annihilates’ toxic PFAS chemicals