I just returned from the Logan Science Journalism Fellowship program at Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., and I’m excited to share some of the things I learned while there. The program itself — which I highly encourage folks to apply to — is different from any other health or science journalism program I’m aware of because there’s pretty much no journalism involved at all. Instead, it’s basic science that journalism fellows do.

Think of it like a weeklong “Career Swap” adventure, where you head to the lab instead of the office and use pipettes instead of pens all day. (And I do mean all day — most days started with a morning talk, followed by lecture and lab at 9 a.m., and we pretty much worked until 10 p.m., except meals and an extra hour halfway through the day.) As a biomedical fellow, I was one of six journalists struggling to recall the organelles of a cell from high school biology before we actually started messing with those organelles.

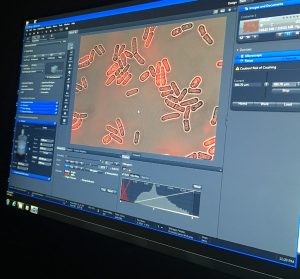

It was during our first experiment — specifically, comparing mitochondria in various mutant yeast cells to the mitochondria in a wild-type (“normal”/control) yeast cell — that I had an epiphany that will undoubtedly influence how I cover medical studies from now on: All those cell images and microscope photos matter.

My realization clearly wasn’t some grand insight — of course the photos included in medical studies matter or else they wouldn’t be there — but I now understand their function in a way I never did before spending hours comparing the phenotypes of mitochondria in a half dozen different yeast cells that had each had a different gene deleted from their genome.

Like the description of statistical analysis described in studies’ methods sections, which I wish I understood better but which usually goes over my head, I don’t usually pay much attention to images of cells or viruses or protein shapes or microscopic things included in papers, whether they’re basic science, clinical trials, exploratory studies or another piece of research. My eye wasn’t trained to understand their relevance so, even though I’d usually skim their captions, they were essentially meaningless to me. I was only focused on the data — or what I perceived to be the only data.

During the fellowship, however, I had to closely examine the physical shapes of mitochondrial strands in the cells we had cultured. I had to find words to describe how they differed and then think about what might cause those differences — and what those differences might mean clinically. My eye wasn’t any more trained to examine those organelles than another layperson’s, but with the guidance of our two instructors, both professor-researchers, I quickly learned to see those images as a scientist would.

The next time I come across microscopy images in a study I’m covering, I may not be able to “see” those images the way the authors did or fully understand what I’m looking at. But I will understand at a much deeper level now that those images aren’t just pretty pictures to break up the gray text. Sometimes they ARE the data, perhaps more important data than the numbers I’m seeking out in the text.