While Medicare may be a cornerstone of keeping older adults healthy and reducing poverty, it’s far from perfect. Closing huge gaps in coverage – some might argue chasms – could improve public health, reduce hospitalizations, help support cognitive function, maintain quality of life and save the health system millions of dollars. But it will literally take an act of Congress for anything to really change.

While Medicare may be a cornerstone of keeping older adults healthy and reducing poverty, it’s far from perfect. Closing huge gaps in coverage – some might argue chasms – could improve public health, reduce hospitalizations, help support cognitive function, maintain quality of life and save the health system millions of dollars. But it will literally take an act of Congress for anything to really change.

At October’s Gerontological Society of America Conference in Boston, experts at the “Medicare, What’s Missing” session examined links between systemic health and oral, vision and hearing health. They looked at some major policy gaps and potential fixes. While everyone agreed more needs to be done, true reform will likely happen by baby steps.

For example, dental care usage rates are down among older adults because of costs and lack of access to care. Twenty percent of older adults have untreated dental decay, usually because retired adults are less likely than younger adults to have any sort of dental insurance, according to Michèle J. Saunders, D.M.D., professor of medicine, dentistry and dental hygiene at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Many beneficiaries are surprised to learn that Medicare does not cover dental care, hearing aids or eyeglasses. Many pensions don’t cover these services either. “Yet there is increasing evidence between oral health and systemic health. Now more than ever, they need access, especially those with comorbid illnesses,” Saunder said.

Tooth loss has been associated with increased mortality and higher prevalence of heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, and aspiration pneumonia. [Oral health topic leader Mary Otto wrote about viewing these associations with some skepticism].

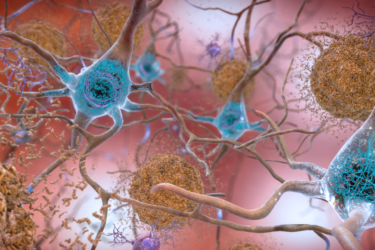

Hearing loss impacts social isolation and can affect cognitive function, dementia and depression. Poor vision can lead to increased risk of falls and diminishes quality of life. And cost is often a defining factor. Older people on fixed incomes will opt for medication or food over hearing aids, new eyeglasses or a trip to the dentist, panelists said. Those with lower income, less education, are Black or Hispanic are disproportionately affected by these choices, according to Saunders.

When Medicare was signed into law in 1965, specialist groups fought to keep their autonomy and avoid what they saw as government interference in their practices However, the needs of our aging population are changing, said Nicholas Reed, Au.D., an audiologist and assistant professor of otolarongology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. More than 38 million Americans have meaningful hearing loss; 45 million over the age of 70 experience unilateral hearing loss. His research found they’ll spend about $22 thousand more on health costs over a decade, are more prone to 30-day hospital readmissions and tend to remain hospitalized longer.

Like vision and dental health, audiology and otolaryngology are side aspects of public health, he said. Hearing aids cost from $4,700 to $12,000 a pair. Surprisingly, fewer than 20 percent of people who own hearing aids actually use them – even the newer, less expensive, over-the-counter models.

“It’s an access issue,” said Reed. “Proper fitting and fine tuning require multiple specialist visits and there’s no Medicare coverage whatsoever.”

The 2017 Over-the-Counter (OTC) Hearing Aid Act allows these devices to be marketed and sold without a prescription. The FDA has until 2020 to produce regulations. But there’s still a disconnect, Reed said. “Medicare Part B covers one hearing exam a year if ordered by a physician for medical reasons. However, the exam cannot be related to a hearing aid, despite the fact that to fit a hearing aid, you have to have a hearing exam.”

In 2018, senators Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Rand Paul (R-Ky.), introduced a bipartisan bill that would allow patients direct access to an audiologist and move that specialty to limited license physician status under Medicare. On the plus side, audiologists could conduct hearing exams, screen for auditory processing disorders, tinnitus and vestibular imbalance. However, hearing aids are still excluded.

Vision care challenges

As with oral health and hearing, vision health is not just some nuisance condition that people experience as get older. It has real consequences for the rest of the body and quality of life, said Heather Whitson M.D., an associate professor of medicine and ophthalmology and deputy director, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University. She was also on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine committee which authored a 2016 report on making eye health a population health imperative.

“Despite increasing recognition of the importance of eyesight, millions of people have undiagnosed or untreated vision impairments, from mild to legal blindness,” she said. “But it’s a de-emphasized piece of health care.”

Between 8 million and 16 million people in the U.S. could have their vision problems corrected in a day, with appropriate eyeglasses or contact lenses, she said. However, Medicare does not cover these simple fixes. They also don’t pay for any other device that contains a lens, like durable medical equipment which helps people read and perform daily tasks.

While insurance covers treatment for age-related macular degeneration, including in-eye injections costing some $4,000 annually, it won’t pay for a simple pair of $100 glasses, which could vastly improve an older adult’s quality of life, help them remain independent and prevent falls. “If I had a patient who lost use of their legs or had amputation, I could get them all kinds of things they need to remain independent. But if they lose their vision, I can’t get them the equipment they need to address that,” she said.

In 2018, the Commonwealth Fund proposed adding optional vision, dental and hearing benefits to traditional Medicare, paid for by a modest monthly surcharge. It’s not clear whether that proposal will make it into actual legislation. Chronic vision impairment is not on the list of 20 covered chronic conditions covered under the 2018 CHRONIC Care Act. This law allows Medicare Advantage plans to offer supplemental services ranging from meal delivery to companion care, to some beneficiaries with certain long-term illnesses. Supplemental vision, hearing and dental plans are available on the open market, but are often cost-prohibitive.

These services for older adults “should be an integral part of public and private health benefits programs including Medicare part B, Medicaid, employee retirement benefits and other health insurance programs,” said Saunders.

The potential exists for public policy to fix these problems and improve coverage. The current political and economic landscapes make funding these additional benefits iffy at best, panelists concluded. But if Elizabeth Warren and Rand Paul can team up on legislation, who knows what might pass?

Journalists:

- What low cost/free programs are available in your community to help older adults meet their vision, hearing or oral health care needs?

- What is the position of your elected officials at the state and federal levels on providing more vision/hearing/oral health care through Medicare or Medicaid, or a state-specific program?

- Talk to older adults in your community about lack of access to these services. Do they pay for them out-of-pocket? Go without? Would they pay a modest premium for supplemental coverage or switch to a Medicare Advantage plan that covers them?