Despite efforts to curb the use of antipsychotic drugs in nursing homes, about 20 percent of residents – more than 250,000 vulnerable individuals – are still given these potent medications, according to a new report from the Long Term Care Community Coalition (LTCCC).

While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) estimates that only a very small percentage of the senior population will ever have a condition warranting use of these powerful medications, psychotropic drugs still are being overused among the elderly, especially for those suffering from dementia, the report concluded.

“What makes me so angry is that this is actively happening,” Richard Mollot, LTCCC’s executive director, said in a phone interview. “Families should know they have a right to ask and to say no to medications that are inappropriate, but may not know to ask.” While FDA restrictions on the use of chemical restraints on people with dementia have been in place since 2005, “it’s still rampant throughout the country,” Mollot added.

Inappropriate antipsychotic drugging of nursing home residents is a widespread, national problem as WFAA in Dallas reports. The Food and Drug Administration since 2005 has mandated black box warnings for antipsychotic drug treatment of elderly patients, but the medications still are frequently used to treat the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Antipsychotics and other drugs often are used as a form of chemical restraint to sedate residents so not only their behavior but also the underlying causes do not have to be addressed by staff. In addition to disrupting social and emotional well-being, these drugs significantly increase risks of stroke, heart attack, diabetes, Parkinsonism and falls, according to the organization. They are not clinically indicated for dementia-related psychosis, and may significantly increase the risk of death when given to older adults with dementia, as this Forbes article noted.

The report synthesizes nonrisk-adjusted data from CMS’ Nursing Home Compare website, which provides information on individual licensed nursing homes across the country. Nursing Home Compare tracks antipsychotic drug use for both short-term and long-term stay residents under the “quality of resident care” tab. The LTCCC report includes the names of facilities in each state that were cited for unnecessary drug use in the last three years (as of the processing date indicated) and is searchable by several criteria. It’s downloadable in Excel (csv) format.

Rates of antipsychotic drug use can vary widely from nursing home to nursing home. I pulled information from several states with large populations of older adults and found high rates of antipsychotic medication use in at least one facility in each state. In the first quarter of 2018, 72 percent of residents at one Queens, New York nursing home were administered antipsychotic drugs; in Lee County, Iowa, 80 percent of residents at one facility were similarly medicated. High rates were found in Pinellas County, Fla., (79 percent), and in Maricopa County, Ariz., (75.4 percent). But nowhere was there more use than in California, where several facilities reported 100 percent of their residents received antipsychotic medication during the first part of 2018.

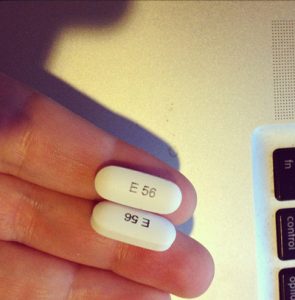

Antipsychotic medications are highly potent drugs indicated for specific conditions and diagnoses, such as schizophrenia. They include drugs such as Haldol, Abilify, and Seroquel. Federal standards require that residents receive the care necessary to reach their highest practicable physical, emotional, and psychological well-being. For residents with dementia, this means that nursing homes must provide care, personal assistance and social services tailored to and appropriate for the individual. The standards explicitly include protections against inappropriate antipsychotic drug use and the use of chemical restraints.

According to these rules, nursing homes should:

- Avoid antipsychotic drugs. Nursing homes must ensure that residents are not given antipsychotics unless the medications are necessary to address a specific diagnosed and documented condition.

- Provide informed consent. Nursing homes must inform the resident, or the resident’s

- representative, of any proposed treatment, in language that the individual can understand. Residents (or their representatives) have the right to refuse treatment.

- Ensure gradual dose reduction. If a resident is given antipsychotic drugs, nursing homes must gradually reduce the resident’s dose unless clinically inadvisable.

State surveyors document inappropriate antipsychotic drug administration under the charge “unnecessary drug use.” As of November 2017, 10,758 deficiencies were found in nursing homes nationally over three previous inspection cycles. While not all deficiencies in this category specifically relate to antipsychotics, the LTCCC estimates that about one-third to one-half of deficiencies may be for the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs. (You can download the deficiencies dataset).

Some of the problems come down to staffing, according to Mollot. Certified nursing assistants (CNAs), the primary caregivers in nursing homes, have a tough job, he explained. Homes are often short-staffed and turnover is high. While the Affordable Care Act mandates that CNAs receive annual training on managing people with dementia, it doesn’t always happen. “They just throw up their hands and do whatever it takes to cope,” he said. “It’s mind-blowing that one-fifth of residents are still getting these drugs.”

This problem extends beyond nursing homes. A recent study found that two-thirds of assisted living residents have a dementia diagnosis and 37 percent of those individuals have received an antipsychotic drug.

Here are some questions for journalists to answer in their reporting on this issue:

- What’s happening at nursing homes in your state? What efforts are being made to address overuse of antipsychotic drugs?

- The Boston Globe reported on similar problems back in 2012. Has anything changed?

- Other articles have appeared in various media outlets, including the Hartford Courant and the CBC.

- Stories about long-term antipsychotic drug misuse also have been linked to the V.A.

- This series in the Naples (Fla.) News examined how the state’s largest nursing home chain survives despite poor patient care.

- ProPublica’s Nursing Home Inspect helps analyze quality and other issues.