PHOENIX – To picture a future in which antibiotics no longer work, all we have to do is look at the past – at the United States before the 1940s when simple infections accounted for a third of all deaths.

“When an antibiotic resistance develops anywhere, it’s a threat to people everywhere,” said Elizabeth Jungman, director of The Pew Charitable Trusts’ public health programs, speaking at a panel on Friday at Health Journalism 2018 that painted a chilling but prescient view of what could happen if and when antibiotics stop working, and we don’t have enough new drugs in the pipeline. “We know what a post-antibiotic world could look like because we lived in a pre-antibiotic world.”

We’re already starting to see the impact of this threat. Panel moderator Maryn McKenna cited statistics from a 2014 Review on Antimicrobial Resistance report that estimated that the global death toll due to antibiotic resistance of 700,000 a year will rise to 10 million annually by 2050.

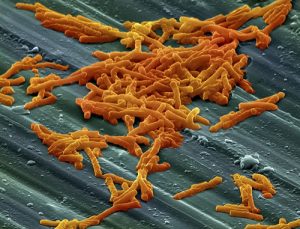

Jean Patel, the CDC’s science lead for antibiotic resistance, introduced the uninitiated to a couple of new nightmare-inducing pathogens: pan-resistant CREs (or carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae) and Candida auris, a multidrug-resistant fungal infection that has only recently started emerging in U.S. hospitals.

Patel told the story of 70-year-old woman considered the first known case of CRE in the United States. The patient, who had recently traveled to India where she was believed to have picked up the infection, died in 2016 after none of the numerous antibiotics used to treat her worked. Patel said the first case of a patient acquiring the disease on U.S. soil has already been reported.

Outbreaks of C. auris are clearly on the rise. Patel said the drug-resistant and potentially deadly yeast infection, which was first identified in Japan in 2009, made its way to the United States in mid-2016 and the number of cases has risen to 261 to date. More than 400 U.S. patients have been found to be asymptomatically colonized, meaning as a carrier they pose a potential source of transmission.

“We’re seeing large outbreaks,” Patel said. “Outbreaks are a challenge to control, and that’s because both the patient and the hospital environment are readily colonized.”

The anemic pipeline for drugs exacerbates fears. The last time scientists discovered a new class of antibiotics was in 1984, Jungman said. Even now, only one in four antibiotics in development represent a novel class – and the reality is few of these drugs will ever make through the pipeline to patients.

“If you think about this as a race between bugs and drugs, the 30-year gap means the bugs are pulling ahead,” Jungman said.

Matthew Wellington, antibiotics program director for U.S. Public Interest Research Groups, described a grim picture of antibiotic resistance focused on the drugs’ preventive usage in agriculture. He said 70 percent of medically important antibiotics go to livestock and poultry.

Resistance may inevitable, but is resistance to that trend futile?

Hopefully not, as many of the panelists highlighted work being done that could shift that trajectory.

Dr. Dennis Dixon, chief of the National Institutes of Health’s bacteriology and mycology branch, stressed the need for a national plan for combating antibiotic-resistance bacteria. He said the NIH and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) have teamed up for the Antimicrobial Resistance Diagnostic Challenge, a $20 million federal prize seeking innovative, rapid point-of-care laboratory diagnostic tests to combat the problem. He said 10 finalists have already been selected. Dixon referenced additional information from his presentation that can be found here and here.

Pew is creating a virtual lab called SPARK (for Shared Platform for Antibiotic Research and Knowledge), an interactive, publicly available database that will allow scientists to collaboration on solutions in real time.

Wellington lauded California for passing Senate Bill 27, the first state law to restrict antibiotic use to treat livestock with infections rather than for preventive reasons. The law went into effect in January. “We need to reserve these drugs for what they’re meant for, and that’s treating illness,” he said.