In February 1918, a Haskell County, Kan., paper, the Santa Fe Monitor, reported almost a dozen people were “quite sick” with pneumonia. At the time, the stories may not have seemed significant. Many people get sick in the winter.

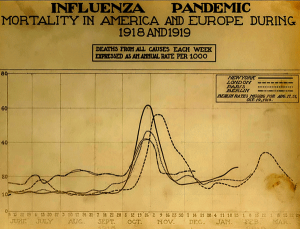

Decades later, however, the stories became hugely important. The Monitor’s report helped disease detectives piece together the trail of the world’s greatest influenza pandemic and its epicenter, according to “The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History” by author John Barry. The 1918 flu, which ultimately killed about 50 million people globally, likely began in Haskell County, where scientists think the deadly flu virus jumped between animals and humans and then to troops at a nearby army base readying to fight World War I.

Why this matters today was highlighted in a Stat story this week by Helen Branswell, “When Towns Lose Their Newspapers, Disease Detectives are Left Flying Blind.” Maia Majumder, M.P.H., a scientist who specializes in mathematical modeling to track infectious diseases, told Branswell that she was alarmed when she recently learned huge areas of the U.S. have no local newspapers. Majumder relies on local news reports, among other resources, as a data source and an early “signal” to identify outbreaks for HealthMap, a website that is considered a key tool by public health authorities and researchers around the world studying disease patterns.

“We rely very heavily on local news,” said Majumder, a Ph.D. candidate at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “There are going to be pockets of the U.S. where we are just not going to have a particularly good signal anymore.”

HealthMap, a 12-year-old disease detection project run by researchers from Boston Children’s Hospital, uses a custom-built algorithm to comb through Internet search engines, news reports, social media, international health organization websites, government websites, infectious disease expert alerts, and even personal blogs of health care workers.

In an example of how important local, on-the-ground reports can be, the site in 2014 reported on a “mystery hemorrhagic fever” in West Africa, nine days before the World Health Organization announced there was an Ebola outbreak.

In another example, there was a mumps outbreak in 2016 and 2017 that was heavily reported by the local Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. The articles were hugely helpful to Majumder because the Arkansas Department of Health wasn’t providing regular updates. If it hadn’t been for the paper’s work, it would have been hard for Majumder to gather research on what was happening on the ground, she told Stat.

HealthMap’s team collaborates closely with the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases (ProMED-mail), a curated Internet-based reporting tool administered by the International Society for Infectious Diseases. The Brookline, Mass.-based ISID represents infectious disease practitioners and it also relies on local news for information it provides to public health officials.

The map that raised Majumder’s concerns was created by Columbia Journalism Review in 2017 as part of an ongoing project to track news deserts. In February 2018, CJR reported further on how local news is relying increasingly on philanthropic funders, such as ProPublica, to support their work.

The Santa Fe Monitor in Haskell County had no such luck. The paper ultimately folded in 1921.

For reporters looking for more data resources to cover outbreaks, HealthMap and ProMed are two of the best.

There are several new infectious disease tracking sites worth checking out. One is Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health’s Influenza Observations and Forecast Map, which relies on the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, the WHO’s collaborating laboratory network, and Google searches for data. Another is DoctorsReport.com which relies on data drawn from the private health care claims database company, IQVIA.com. This site allows reporters to look at illness data based on ZIP codes.