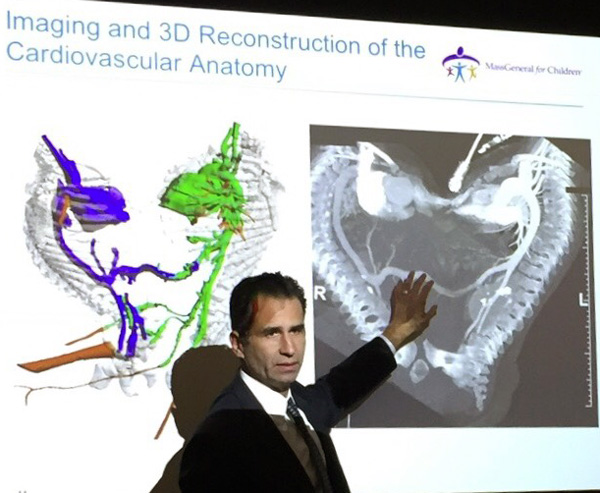

Photo: Gideon Gil/StatDr. Oscar J. Benavidez (left), Dr. Allan M. Goldstein and other doctors at MassGeneral Hospital for Children used a 3-D model of the twins’ anatomy during surgery to separate them.

The twin girls were joined at the abdomen and pelvis. They had two heads and four arms, but three legs. They had two hearts, but shared a liver, a bladder, and other organs. One was active, the other subdued and growing weaker.

Some 20 hospitals had said they couldn’t help the girls, who had been born nearly two years earlier in a village in Africa. But Dr. Allan M. Goldstein, surgeon-in-chief at MassGeneral Hospital for Children, said yes, they would consider operating to separate the twins.

“It falls back to why we go into medicine,” he explained to the AHCJ Boston chapter during a panel discussion Wednesday at the new offices of the Boston Globe and Stat. “We want to try to help you.”

Goldstein and two colleagues candidly discussed the ethical and moral issues raised by the case, the process used to ultimately decide to proceed with the surgery, and the impact it had on the MassGeneral staff.

Imaging showed that one twin’s heart was essentially normal, while the other’s was severely malformed: She had just one ventricle, a misplaced aorta and a grossly inadequate connection to the lungs. She was being kept alive by her sister’s heart and a crucial artery that connected their circulation, said Dr. Oscar J. Benavidez, the hospital’s chief of pediatric/congenital cardiology.

But the girl’s condition was deteriorating rapidly, and if she died, the doctors realized that her healthier sister would, too.

“You could think about these twins as leaning on each other,” Benavidez said. “If one fell, the other would fall.”

The team determined that separation was feasible, but that only one of the twins would survive. That raised a host of ethical and moral questions, said Dr. Brian M. Cummings, chair of the hospital’s Pediatric Ethics Committee. Among the issues they debated: Were the conjoined twins one person or two? Can doctors ever, morally or ethically, sacrifice one for the other? And who should decide — the doctors or the parents?

“They really did have two personalities,” Cummings said. “There were two people there.” The weaker sister — Twin A, as the doctors called her —would sing with her sister and try to swat away the IV lines nurses put in her sister’s arm. “They would play with each other. … That made it very hard.”

Some of the medical staff objected to intervening, saying they can’t do harm and must let nature take its course, Cummings said.

But he noted that the girls’ parents came to the hospital because they wanted to do whatever was possible. “Faced with two bad outcomes, isn’t this the lesser evil,” he asked.

In the end, just three doctors chose not to participate in the surgery because of their discomfort.

“Walking away didn’t seem right,” said Benavidez, particularly as it became clear that Twin A wasn’t doing well.

The surgery was, nonetheless, wrenching. “It was difficult to see them come into the operating room that day because they were both holding rattles,” Benavidez said. He had to take a few moments to regain his composure.

Sophisticated technology guided the team, including a 3-D printed half-size model of the twins’ anatomy and imaging that revealed which girls’ blood vessels fed which patches of skin.

Twin A was still alive as the 14-hour operation neared its end, and Goldstein held out hope that she could survive a few hours, or even days, after the surgery, to give the parents time to say goodbye. But shortly after surgeons cut the artery that joined the sisters’ circulation, she died.

The team took the girl to a separate OR, stitched her up, and brought her to the waiting parents, Goldstein said. “And then I went to a third operating room and cried.”

A year and a half later, the surviving sister is “doing great,” Goldstein said. She has a normal life expectancy but needs more surgery on her pelvis and will likely need one leg amputated. Her parents are reluctant to do that, however.

They and their daughter have lost so much already. At her first office visit after the operation, Goldstein gave the toddler a stuffed animal. She said something to her father in her native language, and Goldstein asked an interpreter what she said: “She said it’s her sister.”