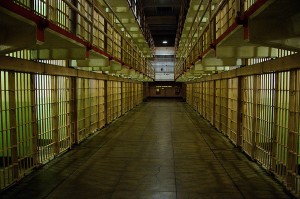

The U.S. Constitution prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. A 1976 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Estelle V. Gamble, declares that prisoners must be protected from “deliberate indifference to their serious medical needs.”

But how does oral health care fit into this picture? Are more than two million incarcerated Americans getting adequate dental services? What is the oral health status of the nation’s prison population? It is hard to say, according to the authors of an editorial in a special June supplement to the American Journal of Public Health.

Oral health studies on this hidden population are scarce. But the research that does exist indicates that prisoners, who often come from poor and dentally-underserved communities, are more likely to suffer from untreated oral disease than the noninstitutionalized population. Once incarcerated, prisoners may face significant barriers to getting needed treatment, according to the writers of the editorial, Nicholas S. Makrides, assistant surgeon general in the U.S. Public Health Service, and Jay D. Shulman, a dentist and professor at the Baylor College of Dentistry.

One of the few studies in which prisoners’ oral health was compared with that of age- and race-matched peers in the general population found that a group of North Carolina inmates “had a substantially higher dental disease prevalence than their study counterparts,” the authors note.

“This is not surprising given that a disproportionate number of inmates come from disadvantaged communities where access to dental care is limited,” they write. And while prisoners have a right to health care under federal law, it is very difficult to know whether the dental care they receive is adequate. The population “is, for all intents and purposes, ‘invisible’” note Makrides and Shulman. Inmates “are not necessarily guaranteed to receive good care; rather, they have only the right to receive care that is free from deliberate indifference to serious medical needs, a low bar indeed.”

To begin to address these problems, the authors call for better data collection and a strengthened system to deliver oral health services to incarcerated people.

They ask that prisoners be included in nationally collected data sets such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

A set of standardized oral health outcome measures for correctional facilities would also help; so would the building of a correctional oral health infrastructure with the help of dental hygiene and graduate dental training programs, the authors write.

But the challenges to improving oral health care for incarcerated Americans are formidable, they warn.

“Finding advocates to champion inmate health care, much less oral health is difficult because this invisible demographic must compete with the interests of a ‘free-world’ population,” they write.

“Our recommendations are just a beginning step in revealing the oral health needs of this overlooked and vulnerable population.”

What do you know about the oral health of incarcerated people in your state or community? Maybe it is time to ask.