Studies that support a link between chocolate and good health are popular with readers. But the reality is that most chocolate studies are observational in nature and are therefore limited in what they can tell us about its supposed benefits.

Skilled health reporters use these kinds of studies as opportunities to gently educate readers about the limits of observational research, such as confounders. Read on for tips on recognizing confounding, factors that confuse or obscure the association between a primary exposure of interest and an outcome, and explaining it to your readers, viewers and listeners.

Here’s a recent case in point—a study published in Neurology called “Chocolate Consumption and Risk of Stroke.”

The study followed 37,000 men in Sweden for 10 years. That’s a plus. Bigger numbers and longer follow-up usually mean more reliable results.

At the start of the study, researchers asked the men to recall how much chocolate they’d eaten in the previous year. That’s the first problem with the study. People are bad at remembering what they eat. It’s called self-report bias. There’s a concise and well-sourced discussion of this major flaw in nutrition studies at the website Unite for Sight.

Based on that one measure, the men were divided into four groups that ranged from those who reported eating no chocolate to those who ate the most, about 63 grams a week. That’s about the size of one-and-a-half regular Hershey bars. They used hospital discharge records to confirm stokes. That was also a strength of the study. Because the Swedish health system keeps extensive medical records on its citizens, it’s unlikely that many strokes went uncounted.

Brenda Goodman, AHCJ’s topic leader on medical studies, is writing blog posts, editing tip sheets and articles and gathering resources to help our members cover medical research.

Brenda Goodman, AHCJ’s topic leader on medical studies, is writing blog posts, editing tip sheets and articles and gathering resources to help our members cover medical research.

If you have questions or suggestions for future resources on the topic, please send them to brenda@healthjournalism.org.

Over the next 10 years, 1,995 men – about 5 percent of the study population – had a first stroke. The men who ate the most chocolate had a slightly lower risk of stroke compared to men who said they didn’t eat chocolate. That would all be pretty suggestive, except that a penchant for indulging a chocolate craving wasn’t the only way the men differed. The biggest chocolate consumers were also younger, more educated, less likely to smoke or have high blood pressure. They also reported eating more red meat, drinking more wine, and eating more fruits and vegetables. With the exception of eating a lot of red meat, those other things also reduce stroke risk. Those are called confounders because they confuse the effect of the exposure (chocolate) on the outcome (stroke).

Researchers adjusted their data to try to remove the influence of those factors. Adjustment is an important step, but it’s not perfect, as Gary Taubes explains in a post for Discover magazine’s Crux blog.

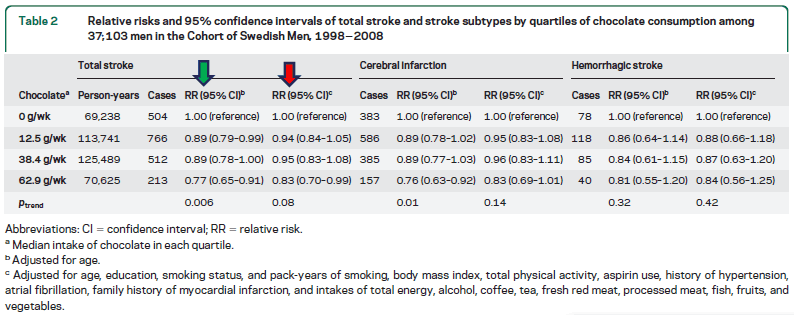

Here’s the table where researchers reported the adjustment (click to view full size):

Here’s a tip about confounding. Look at relative risks (RR) before (green arrow) and after (red arrow) adjustment for confounders for the total stroke numbers. If there’s little confounding in a study, those numbers should be very nearly the same. If they are different, that’s a good indication that confounding is a problem and that there are other factors influencing risk that weren’t measured. For an effect size that’s already small to begin with — just a 23 percent reduced relative risk – these relative risks shrink even more, to 17 percent for the men who ate the most chocolate. Keep in mind, that’s just the difference in relative risk. If 5 percent of the men had a stroke over the course of the study, a 17 percent reduction in that risk would reduce the absolute risk for having a stroke by about .8 percent.

Perhaps recognizing the limits of their own study, researchers took the work a step further and conducted a meta-analysis, a study of studies. Meta-analyses are powerful tools for establishing the weight of evidence. But as Gary Schwitzer points out in AHCJ’s slim guide, “Covering Medical Research,” the quality of a meta-analysis depends on the quality of studies it includes. Two of the five studies included in the meta-analysis found associations between chocolate and stroke risk that were non-significant. All measured chocolate consumption by asking study participants to remember how much chocolate they ate and how often they ate it. There’s that self-report bias again.

When all the results were pooled, chocolate appeared to reduce the relative risk of stroke by 19 percent. Reductions in absolute risk were not reported, but they probably look a lot less dramatic.

That’s a lot to try to explain to readers who are short on time and attention. Here’s how Amy Norton handled it in her story for Reuters Health:

It starts with a deft lede:

Men who regularly indulge their taste for chocolate may have a somewhat decreased risk of suffering a stroke, according to a study out Wednesday.

That’s very different from saying that chocolate may reduce or could lower a man’s risk of having a stroke. The vast majority of stories used that approach, and while it’s not technically inaccurate, words like reduce and lower imply that chocolate is causing the stroke reduction, which is something the study simply doesn’t have the power to prove.

Norton goes on to give the study some context but also to explain why readers shouldn’t go on an immediate chocolate binge (at least not to prevent a stroke):

The study, published in the journal Neurology, is hardly the first to link chocolate to cardiovascular benefits. Several have suggested that chocolate fans have lower rates of certain risks for heart disease and stroke, like high blood pressure.

But those studies do not prove that chocolate is the reason. And the new one, funded by the Swedish Council for working Life and Social Research and the Swedish Research Council, doesn’t either, according to a neurologist not involved in the study.

Other things to like about this story include the use of independent researchers for comment, a discussion about flavonoids in chocolate and why scientists think they may benefit health, and numbers that reflect absolute as well as relative risks.